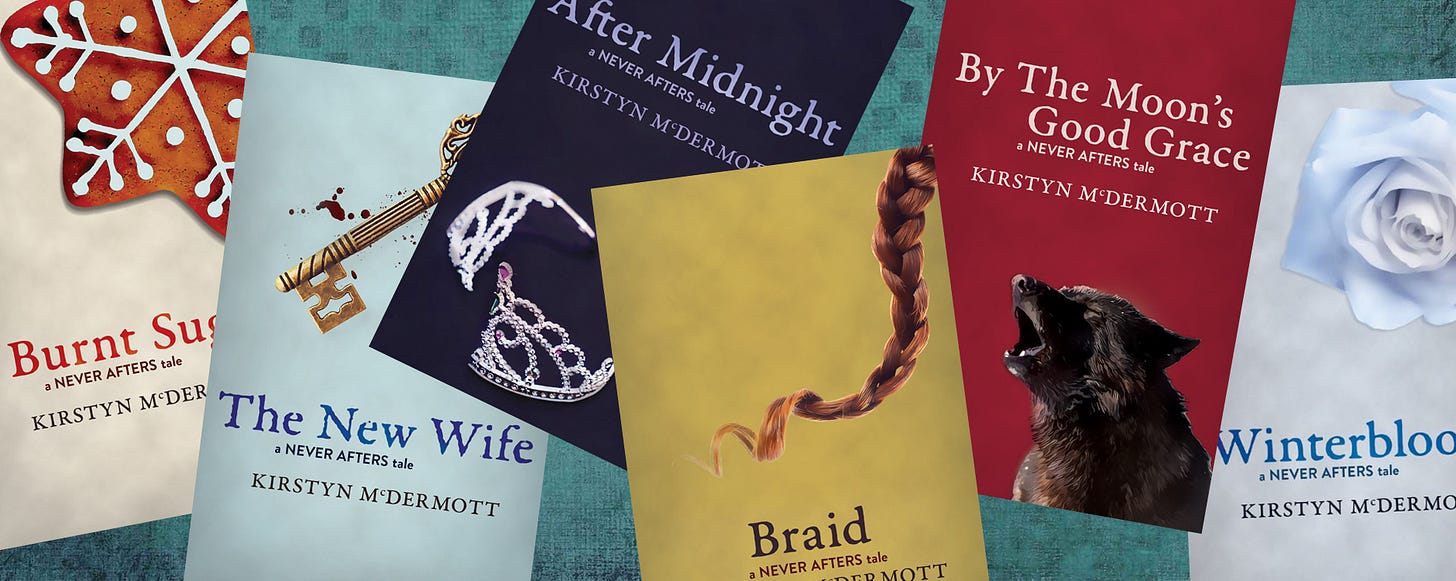

The Orange and Bee had the opportunity to discuss fairy tales and retellings with author Kirstyn McDermott. We are especially thrilled to thrilled to talk about the research and writing of her Never afters series—six novellas that reimagine fairy tales with a focus on collaborative female relationships. Burnt sugar (‘Hansel & Gretel’), The new wife (‘Bluebeard’), After midnight (‘Cinderella’), Braid (‘Rapunzel’), By the moon’s good grace (‘Little Red Riding Hood’), and Winterbloom (‘Beauty and the Beast’) were published as a collection by Brain Jar Press in 2022. Burnt Sugar, originally published in Dreaming in the dark (ed. Jack Dann, PS Publishing Australia), won the 2016 Aurealis Award. Braid, originally published in Review of Australian fiction (Volume 24, Issue 1, 2017), was nominated for the 2017 Aurealis Award and the 2018 Norma K Hemming Award. The new wife was nominated for the 2022 Aurealis Award, and Winterbloom won the 2022 Aurealis Award in the category of novella.

O&B: The Orange and Bee has a central focus on fairy tales, so it seems like a good place to start. When were you first introduced to fairy tales, and how have they impacted the way you see the world?

KM: I don’t have any accessible memory of being first introduced to fairy tales, or at least no memories of a world without fairy tales in them. My mother is a voracious and diverse reader, so we always had a lot of books and among these were illustrated fairy-tale collections and Little Golden Book retellings, both Disney-based and otherwise. As a child, they were definitely among my favourite stories—anything fantastical, or else anything with horses!—but I drifted away from the self-sacrificing maidens and put-upon princesses as I grew older. As a teenager, I was especially sensitive to gender-coding and highly resistant to the constructed feminine—which mainstream fairy tales, thanks largely to Disney, absolutely were. But it all seeps in, doesn’t it? The narratives and characters in which our younger selves are steeped?

So, my relationship with these stories is complicated, and often ambivalent. As an adult reader (and watcher), it was retellings that brought me back to fairy tales—the magnificent work of Angela Carter; the Datlow/Windling anthologies—and I started to explore the sources more deeply. Seeing how similar motifs, themes, and characters are picked up by storytellers the world over, time after time, is a good reminder of the common ground humans have always walked, separately and together. That’s not the same as universality, which flattens our experiences, desires and fears to a bland genericism. It’s more a kaleidoscope that shifts and turns, making complex patterns out of individual shards.

O&B: You started publishing short fiction in 1993. How did fairy tales seep into and shape your work? What other influences did you draw from as you worked to create the unique voice that you are known for?

KM: I have been working largely in the horror/gothic/weird genres since I started writing for publication. It was the place I felt most at home, the genre in which I read and watched the most and where my creative ideas landed. It wasn’t until I was writing my second novel that I came to recognise many of the dynamics, motifs, and themes of traditional fairy tales operating in my creative work, albeit at several removes. Perfections is about two sisters, an ill-thought wish, and the most terrible of sacrifices, and it was a project I struggled with throughout its entire writing. It took me far too long to realise that I was, in essence, writing something of a contemporary fairy tale in the guise of a feminist horror story—but then I leant right in. Unfortunately, that novel got caught up in complicated publisher shenanigans, so it never really received the exposure it deserved—I still believe it’s one of the best things I’ve written. It was also while writing Perfections that I conceived the idea of a collection of ‘post-fairy tales’, which would ultimately lead to a PhD and the Never afters series.

In terms of other influences, I have always read widely and across genres/forms, and I’m likely consciously unaware of much that has shaped me as a writer. Among my early influences in gothic/horror were authors such as Stephen King, Shirley Jackson, Kathe Koja, Ramsay Campbell, Caitlin R Kiernan, Peter Straub, and Clive Barker. Being a stylist at heart, Koja and Kiernan especially! To be honest, I’m far less concerned with my voice these days—although it was a minor obsession when I was a younger writer. Stephen King has a voice, right? You can read a dozen pages of anything he writes, and you pretty much know it’s him. And his voice is remarkable. Kathe Koja as well—astonishing voice. But for myself, now, it’s weird to hear a question about my unique voice as it’s no longer something I’m striving to develop. I’m more interested in the voice that a particular story needs. Perhaps that came out of the PhD as well: all the novellas were first person POV and because they were intended as a collection, the narrative voices could not sound the same. I worked very hard on shaping a voice for each narrating character, for each story, and that writerly intention continues, whether the story is told in first person or otherwise.

O&B: Your work often falls into a mix of genres including gothic, horror, and weird fiction. Do you think that fairy tales are naturally aligned with genres that edge into darker realms of fiction? Do you have any advice for writers when it comes to writing to suit specific forms?

KM: Fairy tales absolutely align with dark speculative fiction. There is much genuine horror in them, especially some of the source tales. Blood and murder and dismemberment, oh my! But also betrayal and grief and terror, the emotional staples of the broader genre we call horror. In my own work, I’m drawn to the darker stories, or even just their darker underbellies. Some truly terrible things happen in fairy tales, even those with supposedly happy endings, and there is often plenty to mine when fleshing them out into contemporary narratives.

When writing in a specific form or genre, the most important advice I can give is that you should know it intimately. This doesn’t mean you have to study its depth and breadth in totality—or complete a PhD!—but you must know its beating heart and how it feels to hold it in your hand. Know the elements, and decide which of those you will be leveraging and which you will set aside. The good thing is, most writers want to write to a specific form because they are already readers of it and there is an urge, perhaps even a compulsion, that comes from love, hate or even spite. So it’s often more a case of stepping back and considering why you want to write this type of story? What will you change, what will you keep? And most important: how do you make it yours?

O&B: The Never Afters series of novellas (Burnt sugar, The new wife, After midnight, Braid, By the moon’s good grace, and Winterbloom) were written as part of the thesis for your PhD in creative writing. How did you select the fairy tales you want to reframe through a lens of female friendship?

KM: Originally, they were not going to be novellas. The plan was for a collection of perhaps a dozen short stories, but once I wrote the first two, I knew I would not able to keep the word length down low enough for that many! Because the stories are all sequels to existing fairy tales, and because I did not intend to rewrite the source tale itself but instead use it as a received backstory to my own sequel (albeit often recast or re-examined), I needed to choose from what I refer to as ‘blockbuster’ fairy tales: the ones with which most people are least passingly familiar, whether it’s from childhood storybooks or, ahem, Disney. The most obscure tale I chose was ‘Bluebeard’ (for The new wife) but even that is moderately well known outside fairy-tale circles.

From that point, it was partly stories that I wanted to push back against, stories that had stuck with me forever like splinters beneath my skin. I loathe the mirror in ‘Snow White’, for example, so I needed to write a sequel where it gets its comeuppance, and also its rightful share of the blame. The evil stepmother situation in ‘Hansel and Gretel’ never sat right with me, and it was intriguing when I started researching the iterations of the tale, to see how the Grimms had changed certain elements. Mostly, the selection was highly personal, and the ideas for what the later lives of the fairy-tale girls might look like developed organically once I started thinking about the particular themes that I wanted to play with. Because I was writing sequels, I was also able to introduce new characters who were not in the source works, and explore friendship and collaboration between women more fully. There are vanishing few female friendships in the historic fairy-tale canon, which was the impetus for my thesis.

O&B: You cite Emma Donoghue, Theodora Goss, Angela Slatter, Aimee Bender, and Kelly Link as creative influences on your work. Do you have any favorite stories to recommend to our readers?

KM: Oh my goodness, what a question. I could give you pages of recommendations, but I’ll keep it brief. First, the entirety of the Donoghue collection, Kissing the Witch, cover to cover. ‘A country called winter’ by Theodora Goss. ‘The color master’ by Aimee Bender. ‘Travels with the snow queen’ by Kelly Link. And for Angela Slatter, I would point people toward the collections Black-winged angels or any of her stories set in the Sourdough world. But I also must recommend ‘Seasons of glass and iron’ by Amal El-Mohtar, which was one of the absolute delights I discovered among the hundreds and hundreds of retold/new fairy tales I read during my PhD research. It’s a brilliant story, nuanced and complex, and one that will live inside my heart forever.

O&B: Do you have any advice for writers when it comes to retelling fairy tales?

KM: This is difficult to answer, as there is no one-size-fits-all advice to give. It depends on why a person wants to retell a fairy tale, their motivation and inspiration, and from what direction they are approaching it, and for what audience the retelling is intended. In general, for me at least, two things are vital to keep in mind.

Firstly, identify the core elements of the source tale or hypotext, the ones that will alert your reader to what it is you are retelling, and choose which of these you will employ and how. For a simple example, a ‘Little red riding hood’ retelling is going to need a significant item of red apparel for the protagonist to wear, but probably not footwear, as this might falsely flag ‘The red shoes’ by Hans Christian Andersen.

Secondly, your retelling should stand on its own two narrative feet in terms of reader engagement and satisfaction. That is, it should be a complete and cohesive story in its own right, even to someone who has never read the tale you’re riffing off, or who doesn’t even realise it is a retelling. It will have deeper resonance for those who know, but shouldn’t rely solely on this knowledge to be an effective story.

O&B: In addition to short fiction, you also write novels. Both Madigan Mine (Picador, July 2010; Twelfth Planet Press, 2014 and Perfections (Xoum, December 2012; Twelfth Planet Press, 2014) were acknowledged with multiple awards, and you recently signed a two-book deal with MIRA Books, an imprint of HQ/HarperCollins. How does your creative process differ across form?

KM: Weirdly (or not), my creative process largely doesn’t change that much between writing short fiction and writing a novel. The latter obviously just takes much more time. I’m a linear writer, even with non-linear narratives, meaning that I do not skip around or write scenes/chapters ahead of the order they will appear in the finished text. I research, edit, and structure as I go, which may mean I pause on the new words for a bit while I figure my way through a problem, and I am a piecemeal planner. I use the metaphor ‘writing by torchlight’ to describe my process: I need a very solid starting point, a vague sense of where I will end up, and then I consciously plan only as much as I can see in front of me at any time.

Occasionally, I have had a short story conceived pretty much from beginning to end and have written those in a handful of days. Mostly, I have a concept/theme and character/s, work out the tone/voice that’s needed, and then just start and figure it out as I go along. Usually, especially for longer works, I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about the story, which helps me get my starting blocks in place and gives me confidence in what I am writing. All that said, the novel I’m working on right now is a different beast. I came up with the basic elements in a single afternoon and had to begin almost immediately, so the writing process is significantly more exploratory for me on all levels as I don’t have the depth of knowledge about my characters/narrative that I usually possess going in. Which makes it . . . interesting. It might also mean actual structural editing will need to be done at the end, which is not what normally happens with the way I work. My first drafts are almost always copy-editing only deals as I’ve done all the structural heavy-lifting along the way. But it’s also been a long time since I’ve written a novel-length work for a deadline, so we’ll see what happens and whether this changes my process for longer works.

O&B: Can you give us a sneak peek into your forthcoming novel, What the bones know? What can we expect?

KM: What the bones know is a ghost story set in regional Australia at the beginning of the pandemic in 2020. Jude returns to the farm where she grew up to care for her unwell mother and becomes trapped there when the first lockdown hits. It’s Jude, her mother, and her young daughter, isolated and alone—or not entirely alone, as it turns out. Hauntings have long been a writerly obsession of mine and it feels like this novel has been waiting in the wings of my brain for a long time. Like all ghost stories, it is about more than simply a haunting. It’s about memory and trauma, and how we can either choose to pass on the awful things that happen to us or accept accountability for them, and what we are left with when we do.

O&B: How do you balance your writing with your other work and responsibilities? What strategies do you use to protect or nourish your writing practice?

KM: I work almost full-time in a non-writing related job, so finding the balance is difficult. I completed What the bones know over the course of around 18 months, including several fallow stretches when life got too busy or exhausting. It’s always hard to get the writing momentum going after a small hiatus, but of course my brain has been working away in the background the whole time, fixing problems, working things out. With this second contracted novel, I don’t have the luxury of time, so my main strategy is to schedule specific writing sessions—often in the evenings as well as on weekends—and to show up for these unless there is a genuinely insurmountable obstacle. Even if I don’t feel like writing, I’ll tell myself to just turn on the laptop and get 100 words down. Of course, I usually end up writing a lot more than that and it’s all words that wouldn’t have been written at all if I’d succumbed to the don’t feel like it impetus and doom-scrolled instead.

Recently, I’ve also started to set a monthly word-count goal and use a tracking app for planned writing sessions. It’s ridiculous how easy it is to hack my own brain—skipping a session would mean a red day on the writing calendar instead of green; not meeting the word count would be coloured yellow. Neither of these is acceptable, so write I must!

The other essential strategy is to say NO to a lot of unnecessary distractions and side quests. I still want to have a social life, and make time to see movies and theatre and go to events, and try to maintain a baseline of health, so I’ve really had to prioritise what I do with the time outside of my day-job. It’s not infinite, funnily enough, and I cannot do all the things. It’s also weirdly liberating to be able to say, ‘No, I can’t do that,’ and just . . . not do it. Time is the one genuinely finite resource we all have, and the older I get, the more zealously I find myself guarding it.

Kirstyn McDermott has been working in the darker alleyways of speculative fiction for much of her career. She is the author of two award-winning novels, Madigan Mine and Perfections, and a collection of short fiction, Caution: Contains small parts. Her stories and poetry have been published in various magazines, journals and anthologies both within Australia and internationally, with her most recent work being Never afters, a series of novellas that retell classic fairy tales. She holds a PhD in creative writing with a research focus on re-visioned fairy tales and produces and co-hosts a literary discussion podcast, The writer and the critic. Kirstyn lives in Ballarat, Australia, with fellow writer Jason Nahrung and two distinctly non-literary felines.

She can be found online at www.kirstynmcdermott.com.