Goonur the woman doctor

Issue five: A traditional tale from the Yuwaalaraay/Euahlayi people people of the Narran Lakes area, as collected, translated, and published by Katie Langloh Parker in 1896

In January, 1862, five-year-old Catherine Stow (Katie) and two of her sisters fell into the Darling River. Her sisters, Jane and Henrietta, both drowned but Katie was rescued by their nurse, Miola, a Ualarai woman. Later, as a young married woman, she went to live on the lands of the Ualarai, on Bangate Station: a property that stretched over 200,000 acres. Over the two decades while she lived there, Katie developed strong friendships with the local Indigenous people, especially the women. She became moderately fluent in the local language, and, through a process she describes as strongly iterative, transcribed, translated, and published several books of the stories they shared with her under the name Katie Langloh Parker.

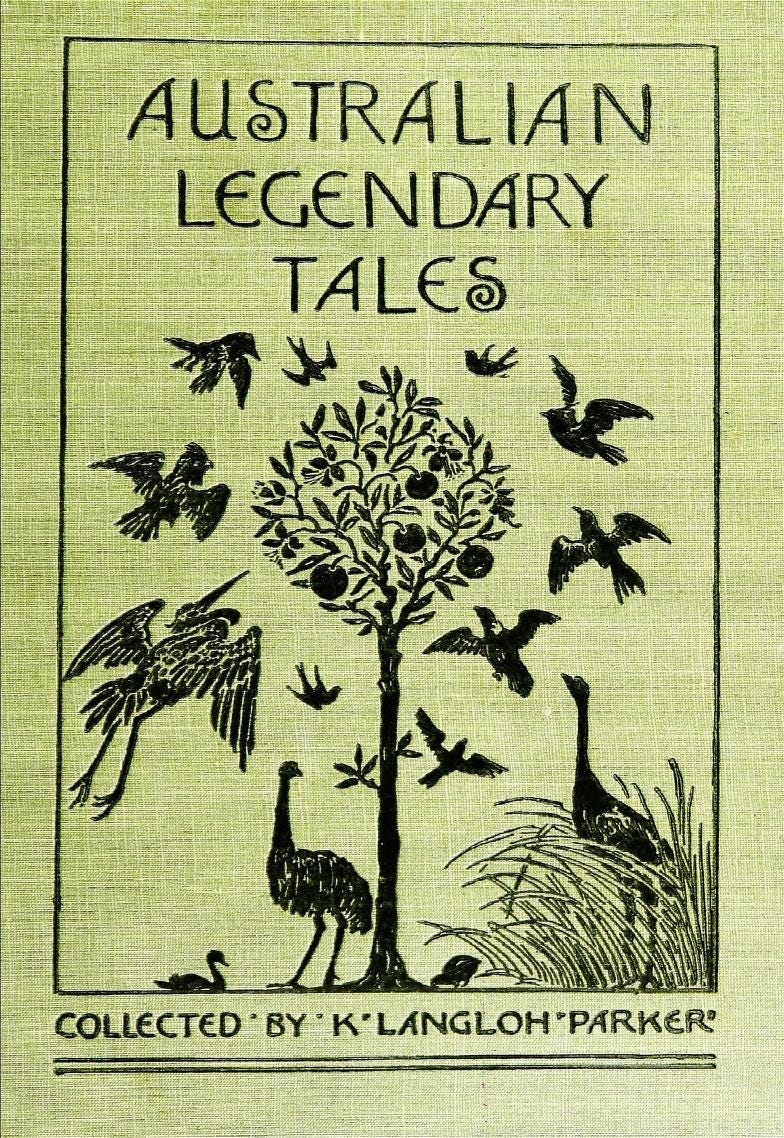

The stories, as Parker acknowledges in her introduction to the first collection, Australian legendary tales (1896) were collected ‘from the Narran tribe, known among themselves as Noongahburrahs’ (1896, p. x). The introduction also includes a brief description of her process of transcription and translation, and an acknowledgement of her:

… great indebtedness to the blacks, who, when once they understood what I wanted to know, were most ready to repeat to me the legends — repeating with the utmost patience, time after time, not only the legends, but the names, that I might manage to spell them so as to be understood when repeated. In particular I should like to mention -my indebtedness to Peter Hippi, king of the Noongahburrahs ; and to Hippitha, Matah, Barahgurrie, and Beemunny.

I have dedicated my booklet to Peter Hippi, in grateful recognition of his long and faithful service to myself and my husband, which has extended, with few intervals, over a period of twenty years. He, too, is probably the last king of the Noongahburrahs, who are fast dying out, and soon their weapons, bartered by them for tobacco or whisky, alone will prove that they ever existed. It seemed to me a pity that some attempt should not be made to collect the folk-lore of the quickly disappearing tribe—a folk-lore embodying, probably, the thoughts, fancies, and beliefs of the genuine aboriginal race, and which, as such, deserves to be, indeed, as Max Muller says, “might be and ought to be, collected in every part of the world” (p. xi).

‘Goonar the woman doctor’ was included in the first of Langloh Parker’s collections, Australian legendary tales, which was originally published in 1896, and included an introduction by Andrew Lang: the English folklore enthusiast most well-known for his ‘coloured’ fairy books. This and the second edition (published two years later, in 1898) included illustrations by Tommy Macrae, who may have been the first Indigenous person to have his illustrations included in a published book.

The second collection includes a lively and engaging introduction by Parker, in which she includes some small portraits of herself learning from the local people. This one, in which she learns about a bright fungus, is particularly delightful:

While walking through the bush after heavy rain, I came across some very brilliant fungi, growing on to dead trees. I picked off a piece, and on my return, going out to speak to some of the Blacks, I carried this fungus in my hand. A little black child, seeing its bright colour, came towards me as if to get it, but his mother quickly interposed, saying in an alarmed tone : ‘Don't let him touch it. It is way-way. Don't let him touch it.’ Then she told me that all fungi growing on trees were the bread of ghosts, and if a child touched any he would be spirited away by the ghosts. She said these fungi were luminous at night so that the ghosts could see them (1898, p. xi).

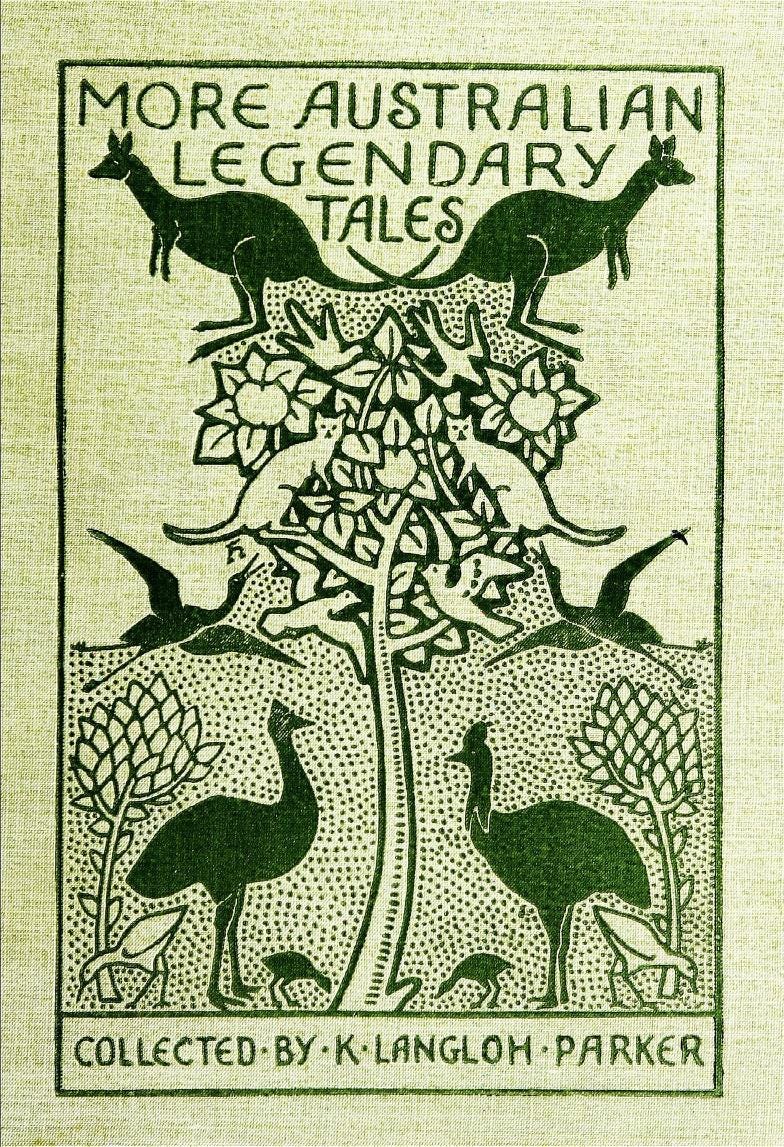

These two books, as well as her third, The Euahlayi tribe: A study of Aboriginal life in Australia (first published in 1905), were well received by the international, white scholarly community. Marcie Muir cites several favourable reviews of her work, including an article in the Australian Anthropological Journal (April 1897), which praised Parker’s rigorous methodology for ‘obtaining from the elders of the tribes what they could furnish, when their confidence was secured by one who knew their language, and could thus understand what they said’. Further noting that ‘It is all the better … that the materials as printed have not been altered by additions of her own imagination, but have been translated as strictly as possible in a true and unaltered manner from the versions given in the Aboriginal speeches by the elders of the tribe’. A reviewer in the periodical Science of Man recommended More Australian legendary tales to the ‘non-scientific’ reader but also suggested that ‘to anthropologists, who have studied similar compositions of other peoples they represent far more interesting characteristics than mere amusement, or fairy tales’.

Here, then, is an example of one of the tales published by Katie Langloh Parker: a story relayed by the Noongaburrah people through a process of iterative translation and transcription to a white woman settler and, perhaps, friend. Nevertheless, as with all well-intentioned works of collection, translation, and publication by settler-colonists of colonised people’s lives and stories, Parker’s work is not without its flaws. As summarised eloquently by Julie Evans:

Tanya Dalziell, for example, views Parker’s publications as irredeemably bound up in the discourses and practices of colonial ethnography and condemns what she terms the analytical trope of ‘the sympathetic white woman’ as similarly repressive in fostering a simple binary of complicity or resistance. As I have discussed elsewhere … there are clearly multiple complexities in utilising a white woman’s writings as sources for understanding Aboriginal cultural practices and beliefs; in the case of Parker’s publications, Yuwalaraay women’s experiences were represented to readers through the lens of a settler woman’s interests and perceptions. Nevertheless … given the paucity of other literary sources for the period, Parker’s writings warrant serious attention for the insight they offer into Yuwalaraay women’s continued care of their land and maintenance of the cultural practices so closely related to it

…

Goodall’s [analysis] … highlights the embeddedness of Parker’s stories ‘in the landforms of Yuwalaraay people’s country’: Story after story tells of ancestral journeys from named place to named place along the Narran and Barwon rivers, explaining why and how each watercourse and its surrounding landforms were created, and the powers each place continues to embody. These stories also explain the connections between kin groups of people, other species and the land, linking them all inextricably … They give us a faint glimpse of the enlivened land, the “speaking land” that south-eastern Aboriginal people saw when they looked around their country before invasion began. Such a glimpse allows us to see how the experiences of the invasion would be drawn into this web of meaning around place (Evans 2011, p. 21).

Goonur, the woman doctor

Goonur was a clever old woman-doctor, who lived with her son, Goonur, and his two wives. The wives were Guddah the red lizard, and Beereeun the small, prickly lizard. One day the two wives had done something to anger Goonur, their husband, and he gave them both a great beating. After their beating they went away by themselves. They said to each other that they could stand their present life no longer, and yet there was no escape unless they killed their husband. They decided they would do that. But how? That was the question. It must be by cunning.

At last they decided on a plan. They dug a big hole in the sand near the creek, filled it with water, and covered the hole over with boughs, leaves, and grass.

‘Now we will go,’ they said, ‘and tell our husband that we have found a big bandicoot’s nest.’

Back they went to the camp, and told Goonur that they had seen a big nest of bandicoots near the creek; that if he sneaked up he would be able to surprise them and get the lot.

Off went Goonur in great haste. He sneaked up to within a couple of feet of the nest, then gave a spring on to the top of it. And only when he felt the bough top give in with him, and he sank down into the water, did he realise that he had been tricked. Too late then to save himself, for he was drowning and could not escape. His wives had watched the success of their strategem from a distance. When they were certain that they had effectually disposed of their hated husband, they went back to the camp. Goonur, the mother, soon missed her son, made inquiries of his wives, but gained no information from them. Two or three days passed, and yet Goonur, the son, returned not. Seriously alarmed at his long absence without having given her notice of his intention, the mother determined to follow his track. She took up his trail where she had last seen him leave the camp. This she followed until she reached the so-called bandicoot’s nest. Here his tracks disappeared, and nowhere could she find a sign of his having returned from this place. She felt in the hole with her yam stick, and soon felt that there was something large there in the water. She cut a forked stick and tried to raise the body and get it out, for she felt sure it must be her son. But she could not raise it; stick after stick broke in the effort. At least she cut a midjee stick and tried with that, and then she was successful. When she brought out the body she found it was indeed her son. She dragged the body to an ant bed, and watched intently to see if the stings of the ants brought any sign of returning life. Soon her hope was realised, and after a violent twitching of the muscles her son regained consciousness. As soon as he was able to do so, he told her of the trick his wives had played on him.

Goonur, the mother, was furious. ‘No more shall they have you as a husband. You shall live hidden in my dardurr1. When we get near the camp you can get into this long, big comebee2, and I will take you in. when you want to go hunting I will take you from the camp in this comebee, and when we are out of sight you can get out and hunt as of old.’

And thus they managed for some time to keep his return a secret; and little the wives knew that their husband was alive and in his mother’s camp. But as day after day Goonur, the mother, returned from hunting loaded with spoils, they began to think she must have help from some one; for surely, they said, no old woman could be so successful in hunting. There was a mystery they were sure, and they were determined to find it out.

‘See,’ they said, ‘she goes out alone. She is old, and yet she brings home more than we two do together, and we are young. To-day she brought opossums, piggiebillahs3, honey yams, quatha4, and many things. We got little, yet we went far. We will watch her.’

The next time old Goonur went out, carrying her big comebee, the wives watched her.

‘Look,’ they said, ‘how slowly she goes. She could not climb trees for opossums—she is too old and weak; look how she staggers.’

They went cautiously after her, and saw when she was some distance from the camp that she put down her comebee . And out of it, to their amazement, stepped Goonur, their husband.

‘Ah,’ they said, ‘this is her secret. She must have found him, and, as she is a great doctor, she was able to bring him to life again. We must wait until she leaves him, and then go to him, and beg to know where he has been, and pretend joy that he is back, or else surely now he is alive again he will sometimes kill us.’

Accordingly, when Goonur was alone the two wives ran to him, and said:

‘Why, Goonur, our husband, did you leave us? Where have you been all the time that we, your wives, have mourned for you? Long has the time been without you, and we, your wives, have been sad that you came no more to our dardurr.’

Goonur, the husband, affected to believe their sorrow was genuine, and that they did not know when they directed him to the bandicoot’s nest that it was a trap. Which trap, but for his mother, might have been his grave.

They all went hunting together, and when they had killed enough for food they returned to the camp. As they cam near to the camp, Goonur, the mother, saw them coming, and cried out:

‘Would you again be tricked by your wives? Did I save you from death only that you might again be killed? I spared them, but I would I had slain them, if again they are to have a chance of killing you, my son. Many are the wiles of women, and another time I might not be able to save you. Let them live if you will it so, my son, but not with you. They tried to lure you to death; you are no longer theirs, mine only now, for did I not bring you back from the dead?’

But Goonur the husband said, ‘In truth did you save me, my mother, and these my wives rejoice that you did. They too, as I was, were deceived by the bandicoot’s nest, the work of an enemy yet to be found. See, my mother, do not the looks of love in their eyes, and words of love on their lips vouch for their truth? We will be as we have been, my mother, and live again in peace.’

And thus craftily did Goonur the husband deceive his wives and make them believe that he trusted them wholly, while in reality his mind was even then plotting vengeance. In a few days he had his plans ready. Having cut and pointed sharply two stakes, he stuck them firmly in the creek, then he placed two logs on the bank, in front of the sticks, which were underneath the water, and invisible. Having made his preparations, he invited his wives to come for a bathe. He said when they reached the creek:

‘See those two logs on the bank, you jump in each from one and see which can dive the furthers. I will go first to see you as you come up.’ And in he jumped, carefully avoiding the pointed stakes. ‘Right,’ he called, ‘All clear here, jump in.’

Then the two wives ran down the bank each to a log and jumped from it. Well had Goonur calculated the distance, for both jumped right on to the stakes placed in the water to catch them, and which stuck firmly into them, holding them under the water.

‘Well am I avenged,’ said Goonur. ‘No more will my wives lay traps to catch me.’ And he walked off to the camp.

His mother asked him where his wives were. ‘They left me,’ he said, ‘to get bees’ nests.’

But as day by day passed and the wives returned not, the old woman began to suspect that her son knew more than he said. She asked him no more, but quietly watched her opportunity, when her son was away hunting, and then followed the tracks of his wives. She tracked them to the creek, and as she saw no tracks of their return, she went into the creek, felt about, and there found the two bodies fast on the stakes. She managed to get them off and out of the creek, for she was angry that her son had not told her what he had done, but had deceived her as well as his wives. She rubbed the women with some of her medicines, dressed the wounds made by the stakes, and then dragged them both on to ants’ nests and watched their bodies as the ants crawled over them, biting them. She had not long to wait; soon they began to move and come to life again.

As soon as they were restored Goonur took them back to the camp and said to Goonur her son, ‘Now once did I use my knowledge to restore life to you, and again have I used it to restore life to your wives. You are all mine now, and I desire that you live in peace and never more deceive me, or never again shall I use my skill for you.’

And they lived for a long while together, and when the Mother Doctor died there was a beautiful, dazzlingly bright falling star, followed by a sound as of a sharp clap of thunder, and all the tribes round when they saw and heard this said, ‘A great doctor must have died, for that is the sign.’ And when the wives dies, they were taken up to the sky, where are now known as Gwaibillah5, the red star, so called from its bright red colour, owing, the legend says, to the red marks left by the stakes on the bodies of the two women, and which nothing could efface.

References

Evans, Julie 2011, ‘Katie Langloh Parker and the beginnings of ethnography in Australia’, in Fiona Davis, Nell Musgrove, and Judith Smart, eds, Founders, Firsts and Feminists: Women Leaders in Twentieth-century Australia, eScholarship research centre, University of Melbourne, pp. 13-26.

Muir, Marcie 1982, My bush book: K. Langloh Parker's 1890s story of outback station life / with background and biography by Marcie Muir, Rigby, Adelaide.

Parker, Katie Langloh (collector, translator) 1896 Australian legendary tales: folk-lore of the Noongahburrahs as told to the Piccaninnies, David Nutt.

Parker, Katie Langloh (collector, translator) 1898 More Australian legendary tales: collected from various tribes, David Nutt.

Bark, humpy, or shed. NB: Katie Langloh Parker provides a glossary of some Indigneous language she has retained in the text. Each of these footnotes are her definitions.

A bag made of kangaroo skin.

Ant-eater. One of the echidanae, a marsupial.

Quandong. A red fruit like a round red plum.

Mars, the red ‘star’.

Thanks for sharing a tale that I otherwise wouldn't have read. It is always a joy to me that across cultures, continents and vast spans of time, although the settings and some specific references change, the stories humans tell are of complex relationships and love.

In contrast to this folk-lore tale,I am currently reading The Woman in White by Wilkie Collins, published as a series by Charles Dickens in the late 1880s. I had a similar feeling of familiarity and illumination when I read his line about the young people being more concerned with serious things in the world, while the older generation can see the mirth in their circumstance. It struck me that what is true today was obviously true when he was writing and observing society.

Are we all really just telling the same story?!