The Orange & Bee are delighted to publish Kari Maaren’s marvelously strange and magical story, ‘Made to be broken’.

We are grateful to our paying subscribers, who allow us to keep publishing great stories, poems, and more. If you haven’t already, please consider signing up or giving a gift subscription.

‘The hole in the sky is spitting out babies again,’ said the crow.

In the midst of her churning, the curator paused. She had become used to the crow’s way of putting things. He didn’t see the world as she did, but like her, he appreciated potential sources of fresh meat. ‘I’m sure it can’t be,’ she said.

‘I was there,’ said the crow, hopping onto her shoulder. ‘Big baby with blue legs came screaming through the sky. Heading this way now. Told me I was a “handsome specimen”. What’s a specimen?’

‘A type of fish,’ said the curator, who had never in her life admitted to not knowing something.

If the crow had seen someone fall, someone had fallen. The curator stood and set the butter churn aside.

‘Is this one of the food ones?’ asked the crow.

‘How should I know? What was your sense?’

She could feel him tilting his head; his feathers brushed her cheek. ‘Probably female? Talked to the elm tree but didn’t notice the goats. Didn’t throw rocks or cry. Or have anything collectable.’

She tried not to notice the little stab of disappointment she felt at those words. Everything’s fine, she told herself, nipping inside the house to open the windows and build up the fire.

She had little to prepare. The main room of the house was small and cozy, and she kept it neat. The spinning wheel and the loom were tucked into their alcoves, the pots and pans were hung beside the hearth, and the door to the other room was firmly closed. The cat, which only talked to her when she didn’t want it to, stretched insolently on the windowsill.

‘I hope it’s one of the food ones,’ said the crow.

I hope it’s not.

Uneasiness prickled over her skin. It had been a long time. And the … visitor … had talked to the tree but missed the goats.

That’s not how the story goes.

Maybe this one will be different.

They’re not supposed to be different.

‘Dibs on the eyeballs,’ said the crow.

The crow had been right: the visitor was a girl.

She was in her late teens, which was the right age, but clearly fashions had changed in the world above. As the crow had said, the girl had blue legs, or at least legs sheathed in blue cloth. Short black hair framed a face alive with curiosity.

‘Hey,’ she said.

‘They usually say “Greetings, dread mistress”,’ the crow observed from a tree branch.

The girl spared the crow a glance. ‘Animals talk here. And trees. Clearly, I’m not in Kansas anymore. Which of the witches are you?’

'Wrong word. Just eat her now,' said the crow.

The curator knew any attempt to quell him would be useless. When he got like this, it was better just to let him talk himself out. Personally, she had no issue with being called a witch. ‘I’m the curator,’ she said. ‘Come in if you like.’

‘Okay,’ said the girl. ‘But, you know … you’re not going to eat me, are you?’

The curator paused.

Everything felt off balance. They usually didn’t ask. They did what they were told, or they didn’t. Most of the ones who didn’t end up eaten were cowed anyway, with shadows under their eyes and bruises on their wrists. The others were rude from the start.

‘Not right now,’ she said.

‘Cool,’ said the girl, and followed her into the house.

There was a way these things always went. Surely, thought the curator as she moved from twilight to firelight, they would go that way this time, too. The girl had fallen from the world above. The curator knew there had to have been a time people hadn’t fallen, back before the crow and the house and the cat. She couldn’t remember that time, of course—

Can’t you?

—but there were only ever three reasons anyone fell from the sky.

‘Hey,’ said the girl. ‘Thanks. I mean, I don’t know exactly what’s going on, but I guess maybe … you know how to help me? My name’s—’

The curator held up a hand, and the girl fell silent.

‘Yes,’ said the curator, ‘I can help you if you do as I ask.’

She never let them give her their names. It wouldn’t do to become too attached.

It was generally understood by the people who fell from the sky and probably weren’t going to end up eaten that tasks would be required if they wanted what they’d come for. The tasks, the curator told herself, would get them back on track.

She started small. 'Take the spinning wheel for a bit. One skein will do.'

'Sounds good,' said the girl.

Maybe, thought the curator, this was going to work out after all.

The girl sat down at the spinning wheel, set her foot to the treadle, and spun the wheel. She got up a good speed and pumped away, the very picture of industry.

After a time, the curator realised she, the crow, and the cat were standing in a row, watching in fascination as the girl spun empty air.

The crow broke first. 'Why?' he said. He knew what spinning was, even if he had never grasped exactly what it was for. 'Why spin the wind? Is it magic?'

'Oh, I’m sorry,' said the girl, stopping. 'I thought this was right.'

'You … you have to …' said the curator. There was no real way to finish the thought. The girl clearly didn’t know how to spin.

'Maybe just sweep for now,' said the curator.

'Sure,' said the girl.

But she couldn’t sweep either. 'We have a Roomba,' she said when everyone stared at the way she held the broom wrong and fanned it above the floor as if trying to waft the dirt away. The strange word just made them stare more.

The curator set her to peeling vegetables.

She had never known anyone to slice open four fingers on both hands at a single stroke.

‘I’m totally going to get this,’ said the girl, bleeding all over the carrots.

‘Eat her now,’ said the crow as the girl used her bandaged hands to dust a shelf. A bowl fell to the ground and shattered. The curator winced.

The problem, of course, was that they couldn’t eat her now.

People came to the house for three reasons. They came because they were running away from something. They came because they were running towards something. Or they came because they were imitating someone who had chosen one of the first two options. It was people in the third category who invariably broke the rules and ended up eaten. That was how it went: you refused to work, and your bones were packed in a chest and sent home to your mother. Everybody knew that.

The girl wasn’t refusing to work. She was simply extremely bad at it.

‘What’s this?’ she said when the curator, in desperation, set her to washing dishes. The girl waved a hand in the air, and a round white object slipped from her injured fingers and nearly knocked the cat off the windowsill.

‘Soap,’ said the curator. ‘If you’ll just slow—’

‘What’s this?’

‘More soap. Please—’

‘Oh no,’ said the girl as a plate hit the floor and broke in two. ‘That wasn’t soap.’

‘Unpleasantness,’ said the crow from his refuge behind the loom.

After the girl upended the butter churn into the stew, the curator admitted defeat.

‘Just … sit there,’ she said. ‘Beside that door. Try not to move.’

‘I’m really sorry,’ said the girl, plopping herself down against the wall. ‘Chores aren’t like this where I come from.’

The curator bit her lip.

The visitors were all the same. All of them, for whatever reason, had gone out into the world. The useful ones would be rewarded, the wily ones would steal, and the lazy ones would be dinner.

But this girl didn’t seem to be running to or from anything, and she certainly wasn’t imitating anyone. She wasn’t useful or wily or lazy. She was just … here.

The curator said, ‘Why did you fall down from the upper world?’

‘You mean through the manhole? I don’t know. I guess I wasn’t paying attention.’

The curator paused briefly over the strangeness of manhole. They usually said well.

‘Yes,’ she said, ‘but why were you there in the first place? Was something worrying you? A bad step-parent? Cruel sisters? Some kind of curse?’

The girl tilted her head in a way that reminded the curator of the crow. ‘Well, no. Both my moms are all right. My sister’s a dork, but we get along okay. And we don’t get curses where I come from.’

She needed to make it make sense. If it didn’t, it was as if she was back in the time before—

No. They all come here for a reason.

‘Hey,’ said the girl, ‘what’s behind this door?’

‘That’s for later,’ said the curator sharply.

But the girl was already on her feet and tugging at the handle.

‘No. I said—’

‘Sorry. I lack impulse control.’

The girl opened the door.

This isn’t the right order! She has to earn—

I’m not sure things are going to go in the right order today.

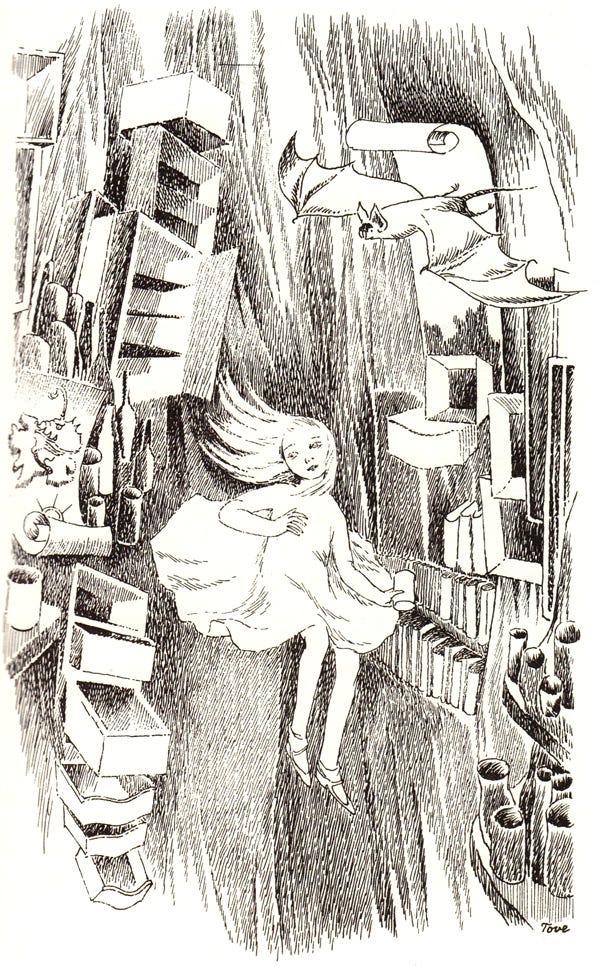

By the time the curator entered the collection room, the girl was admiring the contents of the shelves.

There were a lot of them. The room had grown over time, the shelves constructing themselves as more were needed. The curator couldn’t remember where all the items had come from. Some had arrived here with visitors and been exchanged for other things, but others …

I dreamed them, I think. I stopped at some point, but I used to do that a lot.

She had expected the girl to touch everything, but the girl seemed startled into a kind of awe. ‘Wow. These are … what’s this one?’

‘A cloak of darkness,’ said the curator.

‘What about this one?’

‘Oh, that’s just one of the wishing rings.’

As always when she was in here, her discomfort was growing.

She followed the rules. She was happy to give bits of her collection away to worthy visitors or let the cunning ones steal an item or two. She didn’t keep what she didn’t need. But she didn’t like thinking about this room unless she had to.

The girl was examining a flaming sword. ‘You asked how I ended up here,’ she said. ‘If anything was worrying me. It’s not my family. It’s just … everything.’

‘Everything?’ said the curator.

The girl said, ‘Have you heard of climate change?’

And she told the curator about her world.

The crow and the cat crept into the room at some point, though the curator wasn’t sure when. All she knew was that eventually, there were three of them listening to the girl talk about rising sea levels and inflation and how nobody could afford a place to live and mass shootings and mass deportation and fascism and racism and new laws that were scarily similar to old laws and billionaires and xenophobia and the minimum wage. She described the Internet and the alt right and the way everybody seemed overly worried about who went into which bathroom. She spent a short time on the problems with generative AI and much longer on the potential for nuclear war.

It’s like the whole world is an evil stepmother, thought the curator at one point, through a haze of horror.

The girl fell silent. She had spoken matter-of-factly, as if reciting a list of ingredients.

Her eye fell on a pair of seven-league boots. ‘Nice,’ she said. ‘Can I have these?’

‘Yes,’ said the curator.

Something had shifted.

None of this was following the rules. But … the rules. The rules you made. The rules that didn’t exist until that day—

I don’t remember that day.

Of course you do.

Of course she did. Of course she remembered being … that … long before she had known what time was, or language, or stories. When she had been a sort of spider sitting in a hole, just a stomach and too many eyes. And then someone had fallen into the hole. Someone small and alive and frightened. And she had opened her mouth, which was all she had known to do back then, and the someone had held up something pointy and made of wood and wrapped, enticingly, in fibre. And she’d had her first thought (What is that? I want it). And everything had opened up around her, all the possibilities, all the webs with stories in them. The frightened girl clutching the spindle had seen the monster shrink and flex into something more like her. And the monster had sat down on the ground and demanded the girl teach her how to spin.

Later, it had all got more orderly, delimited by rules upon rules. Later, there had been the house and the crow and the cat and the collection, and the stories had come to her, one at a time. She still got to eat some of them, and that was how those stories ended. Others she sent back out into the world.

The girl picked up a glowing sword. ‘What about this?’

‘That too,’ said the curator.

The people who came to her went away with what they needed.

What do you need when the problem is everything?

She’s only going to cause chaos. Look, she’s got hold of one of the time rubies.

Maybe chaos is what her story needs.

‘This one’s so pretty,’ said the girl, her hand on the blue knife of destiny.

The curator nodded. ‘Take whatever you like.’

When the girl set out for her world again, she was loaded down with more magic objects than the curator remembered having. Getting back would be no problem for her; she had picked up at least five transformation rings and a pair of detachable wings.

She was bubbling over with excitement, which puzzled the crow. 'What’s it even all for?' he asked as she unlatched the garden gate.

‘I don’t know,’ said the girl. ‘I’ll have to make it up as I go along.’

The curator didn’t hear the rest of the conversation because she went back to the house to pack.

The animals came to watch her. ‘Good idea?’ said the crow.

It probably wasn’t. But continuing on as usual wasn’t a good idea either: being a curator, never changing, crouching forever at the bottom of a hole. Maybe there were other places to find, and other rules to break.

She shrugged on her pack. ‘Not sure,’ she said. ‘But I think I’d like to go out into the world.’

The crow hopped onto one shoulder and the cat onto the other.

‘Dibs on the eyeballs,’ said the crow.

Kari Maaren is a Canadian writer, cartoonist, musician, and academic. Her first novel, Weave a circle round (Tor Books, 2017), won the Copper Cylinder Award and was a finalist for the Andre Norton Nebula Award and the Sunburst Award. She has an active webcomic, the award-winning It never rains, and her short fiction has appeared in the anthologies Figments and fragments and Tales from the silence. She lives in Toronto, surrounded by books.

“It’s like the whole world is an evil stepmother…” IS SUCH A GREAT LINE! What a fairy tale for our times!

Delightful! Wonderful rhythmic storytelling, and not a wasted word.