The orange and bee are delighted to offer our readers this extract from Melissa Ashley’s novel, The bee and the orange tree (2020). A meticulously researched and vividly imagined work of historical fiction inspired by the life of the fairy-tale conteuse, Madame Marie Catherine d’Aulnoy.

As well as the extract below, we’re pleased to share an interview with the author, in which she offers a deep and considered insight into the impact that fairy tales (and other folklore) have had on her life and work as a writer.

For now, however, let’s dive into the deliciously imagined world of Melissa Ashley’s novel.

It's 1699, and the salons of Paris are bursting with the creative energy of fierce, independent-minded women. But outside those doors, the patriarchal forces of Louis XIV and the Catholic Church are moving to curb their freedoms. In this battle for equality, Baroness Marie Catherine d'Aulnoy invents a powerful weapon: fairy tales.

In this extract, we ecnounter Mme d’Aulnoy at a salon, where she performs a reading of her fairy tale, ‘The white cat’ for an appreciative audience, reflects on her writing process, and considers the various influences on her work.

30 March 1699

Paris

Marie Catherine pressed her lips together, closing her eyes. The trout pâté melted into a fatty tingle of fish, brine and cream. What did a stutter of indigestion later matter? With only crumbs left on her plate, she glanced at Nicola for permission, received a disinterested nod, and helped herself to her friend’s bread. ‘What would I do without you? I missed you in the kitchen this morning, bossing the staff. Madame d’Airelle’s meringue is oversweet.’

‘Nobody needs me.’

Marie Catherine swallowed, narrowing her eyes. ‘What’s brought this mood upon you? Where’s my assistant disappeared to?’

Nicola toyed with her fork, resting it beside her plate. She removed a handkerchief from her sleeve and dabbed her lips. She leaned closer to Marie Catherine, blinking dramatically. ‘I spent this morning conversing with Lucifer himself.’

Marie Catherine flicked at a crumb on her bodice. ‘We should all be so lucky.’

‘Mathe tried to cheer my spirits. She took me to her soothsayer. The best in Paris. It was supposed to be a treat.’

‘And what did this fortune teller predict that has you out of sorts?’ said Marie Catherine indulgently. Poor Nicola was far too easy to tease.

Nicola regarded her friend Mathe de Senonville, seated several tables away, fending off the advances of two notoriously loose-lipped matrons. As if intuiting her scrutiny, the trio glanced over, averting their eyes quickly and tightening their huddle. ‘She foretold that in a few months I shall have the better of my enemies. That I’ll be beyond the reach of their malice.’ She grasped the tablecloth in her fingertips, a pair of pale house spiders either side of her plate. ‘What a cruel lie to dangle before me.’

‘It sounds like the standard fare of such charlatans. And good news at that. What’s unsettled you?’

Nicola clasped her finger-webs. ‘Monsieur Tiquet’s health is too strong for me to reckon upon a happy ending.’

‘I thought you brokered a truce?’

Nicola shrugged. She dipped a finger in a puddle of caviar and brought it to her lips.

‘You must count your blessings, my dear. Think of your pretty son, who brings such delight. You, of all wives, have managed to thwart the state, even when the odds are so stacked against us. Between you and me, Madame du Noyer also has a husband who runs up debts, and she hasn’t the funds to challenge him as you did. Your wealth is in your own hands. Do you know how rare that is? You are free, my dear. What licence you’re granted to distract yourself from your husband’s petty furies! Yes, he’s flighty and unpredictable, but he lacks the means to your purse.’

Nicola held Marie Catherine’s gaze. ‘My inheritance doesn’t prevent his encroachments on my freedom. He’s turned my staff against me. He’s taken to locking me in my rooms at night. I wish I were more like you, with an iron shutter guarding my heart. Had I your courage—’

Marie Catherine glanced at the clock on the mantlepiece, a monkey orchestra set out beneath the brass hands. The supper break was almost finished and she needed a moment to gather her thoughts before the salon commenced. She’d lost count of the conversations they had shared about brutish husbands. She repeated the advice she always delivered at their end: you are more capable—of creating meaning, of finding pleasure—than you allow yourself to believe.

‘Look around you, Nicola,’ she insisted. ‘Each of us here has the capacity for invention, and you’re no slouch. You surround yourself with beauty, you have a gift for it. Perhaps you need to go a little further in your efforts to make peace in your home. Why not imagine he no longer exists? Surely that would relieve your suffering. His barbs will fall short of their target.’

‘Yes,’ replied Nicola, sitting back in her chair, tapping the base of her wine glass. ‘Yes, you’re right. It’s easy to forget.’

‘Pay no heed to that predictor of fortunes; you must forge your own. Take it as a warning that you must always act to improve your circumstances. Perhaps that’s all that has been foretold.’ Marie Catherine paused. ‘Though I’m not pleased to hear Monsieur’s locking you up. Remember you have me if you ever need counsel. You cannot live in such a manner forever.’

‘It’s not utterly gloomy,’ whispered Nicola, bringing the wine glass to her mouth. ‘Claude’s valet, whom I trust absolutely, doesn’t always obey his master.’

‘A small mercy. Good. Forgive me, but I insist you resume your seat with Mathe. She’s looking forlorn. Let’s start immediately our pledge to enjoy the remainder of the afternoon.’

Attendees of Marie Catherine’s salons were various: from the humorous Madame de Calmet, wife of a magistrate and enthusiastic versifier of animals, to the formidable Abbess de Mongault, head of one of Paris’s most respected convents, whose tales were of a most earthly nature. For each guest, along with the promise of jousting wits, lay the hope that the future son or daughter of Parisian letters might be discovered: the statesman, poet, playwright, philosopher, actor—riddle-maker even. For it was at these salons that the glimmers of such talents were first displayed, and, most importantly, recognised.

Marie Catherine’s gaze swept over her favourite books, shelved in handsome cabinets behind her writing desk. Her dear Greek playwrights and philosophers; the audacious Roman poet Ovid; the Italian tales of bawdy peasant life intermingled with folklore and magic written by Boccaccio, Basile and Straparola. King Henry IV’s elegant grandmother Madame de Navarre, whose Heptaméron had struck Marie Catherine open like a dagger, piercing the heart of her desire to take up her pen.

While she knew intimately the stories of the important men of her own century—Racine and Molière, La Fontaine and Pascal—it was to the peers of her own sex that she had accrued her real debt: the novelists Madame de La Fayette—how she adored the Princess of Cleves—and the Comtesse de Murat, her Trip to the Country detailing life in the provinces from the perspective of a Parisian aristocrat undertaking a little jaunt. But it had all started with Mademoiselle de Scudéry, whose thirteen volumes of Clélie were spread across an entire shelf of Marie Catherine’s bookcase. Her favourite story was ‘Land of the Sauromates,’ from the novel, The Story of Sapho. Mademoiselle de Scudéry was a great rebel, aligning her philosophy with the Greek poet from the Isle of Lesbos, inventing a utopian society composed entirely of women.

Though some criticised de Scudéry for being old-fashioned and unapologetically female, Marie Catherine held only admiration for the stately writer. De Scudéry’s notion of les précieuses, or learned women, was the inspiration for her salon. She had wanted to create a place where women might recite their works, rejecting the cruel satirising of female writers by famous men of letters—Molière, Boileau, Perrault. She felt it her duty to lay bare the dark and piquant potential of women unafraid of their own minds.

A bell tinkled, and slowly the salon dissolved into silence. ‘We’ve arranged a special treat,’ began Madame du Noyer. ‘I wish to call Baroness d’Aulony to take the stage to charm us with a fairy tale. It’s been far too long since we were indulged.’

Ignoring the vigorous tapping of forks on glasses, Marie Catherine allowed Sophie to raise her to her feet. She arranged her features into an expression of nonchalance, holding her head high as she hobbled to the chair set before the balcony curtains. She stood silently before the receptive gathering as a wave of fear lashed her brain. She smiled at her devotees, recalling—her trick for courage—the letters her readers had sent after the publication of her collection of fairy tales, expressing their appreciation and delight. But it was no use. Her mind was quite empty. She had begun to avoid her writing desk, hopeful that the blankness she felt there would be swept away when she next faced an audience. Would she never again have the pleasure of a new story unfolding upon the stage?

She loosened her shoulders, her cape falling in magnificent folds. She let out a slow breath, felt the beetle’s carapace of performance settling around her. Why should she be concerned? She knew precisely how to pace her sentences to unfold the plot of a story, to mimic the voices of her myriad characters. She had a honeyed tongue.

She gazed at the assembly and picked out Alphonse, his expression open and encouraging, urging her to begin. Angelina sat next to him, her head held at a slight angle, her chestnut hair combed high off her forehead, which emphasised the graceful tilt of her chin. Catching Marie Catherine’s eye, she leaned over and whispered into Alphonse’s ear. He responded, his words causing her youngest daughter to blush. But she quickly recovered, rewarding him with a full smile and a lingering glance from her large, coffee-brown eyes.

Yes, thought Marie Catherine, she had made the right choice in introducing them: Agnelina’s astute and considerate manner would no doubt compliment Alphonse’s impulsive, dazzling forwardness. Though many young men attended her salons, she rarely found their writing as interesting as that of her fellow women, but Alphonse was a fascinating exception – and she was sure that Angelina would agree. Her daughter had been served well by the nuns, emerging into womanhood without the coquettishness and jocularity of her spoiled peers. Angelina’s careful speech combined with the expressiveness of her features was a powerful brew; Marie Catherine wondered if Alphonse had noticed. Though her daughter was free to determine her future—Marie Catherine had promised not to interfere—she could not help indulging the pleasant thought.

Which reminded her of her signature fairy tale, ‘The White Cat.’ That was the solution. She would recite it especially for Angelina and Alphonse. Though it was the length of a novella, there was a shorter version—the original bones—which she had composed in a salon game many years before. As if she were a conduit, she began to speak, following the familiar grooves of the tale.

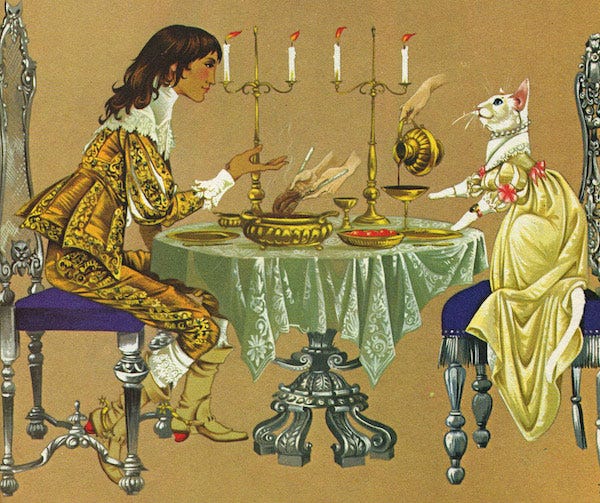

‘The White Cat’ opened with an ageing king, fearful that his sons would usurp his kingdom before his death. He invented a quest for them to undertake, sending all three out on an adventure to find three things: the world’s smallest dog for a pet, a cloth so fine it could be passed through the eye of a needle, and, lastly, a princess with whom the victorious son could rule when the king died. The three brothers departed on their separate journeys. At the beginning of his travels, the youngest son was offered refuge by White Cat, a highly cultivated feline who resided in a magnificent palace, tended by hundreds of servants. The prince’s toilette and dining were performed by disembodied gloved hands, and he was entertained, night after night, by hunts, jousts, operas and fêtes. Of course, the prince forgot all about his quest until, on the very last day before he was meant to return to the king, White Cat presented him with an exquisite gift for his father.

The youngest prince arrived, and removed the walnut from its box, which was ornamented with rubies. Inside it was a hazelnut; and inside that was a cherry stone; the cherry stone was cracked, to show its kernel; which was opened, to reveal a grain of wheat, and inside the grain of wheat, a millet seed. In his mind, the prince questioned White Cat’s intentions, wondering if he had been duped. He found his hand scratched and bleeding from an invisible paw. However, he opened the millet seed and from inside withdrew a piece of linen four hundred ells long, painted with birds, fish, trees, planets, stars, shells, rocks; portraits of the king and other sovereigns, mistresses, children and subjects. The needle was brought forward and the linen passed through its eye six times . . .

Writing the tale, Marie Catherine had discovered her talent for inventing miniature worlds. She felt such pleasure in creating her imagined palaces and kingdoms that she could not stop, and embellished them to perfection, to delight both herself and her readers.

But ‘The White Cat’ was only partly about the quest of the young prince. It was also the story of the feline heroine, who was secretly an enchanted princess. The prince’s real test was to prove his love for her and thereby break the spell she was trapped under. The scene in which White Cat asked the prince to cut off her head and paws to escape her curse still made Marie Catherine tremble in its daring. The message hidden in the story for her listeners was the triumph of true love: both the hero and heroine created their own futures, rather than obeying the customary paths laid down by their families.

‘The White Cat’ prompted a burst of appreciative clapping. Buoyed by the applause but physically spent, Marie Catherine beckoned for Sophie to support her back to her seat, where she would indulge in a welcome glass of wine.

Madame Pipette was rapidly approaching her table, urging forward her coltish fifteen-year-old daughter—she couldn’t recall her name though the pair were regular attendees.

‘Dear Baroness,’ Madame smiled, her dark eyes like little raisins pressed into gingerbread. ‘May I present my daughter, Mademoiselle Sidonie. She’s very taken by your story.’

Marie Catherine offered her cheek to the gangly young woman, who stood a full head taller than her mother.

‘She aspires to be a conteuse,’ whispered Madame, thrusting her chest forward, the flesh spilling from a softly crinkled bodice. ‘Perhaps you have a word of advice. All she does is scribble in a notebook. It’s most alarming.’

The girl stared at Marie Catherine, her expression filled with admiration. ‘What if I wished to share a tale? I have one I like very much. Though I fear it might be silly. More for the nursery.’

Marie Catherine smiled indulgently. ‘Don’t be ashamed of your writing. It’s a gift even to have the desire to turn your thoughts into stories. You must be sure to practise, though, if you wish to progress beyond nursery stories. I suggest you read Mademoiselle de Scudéry’s novels: they’re filled with instructions about how one might cultivate and display one’s wit and ideas.’ Marie Catherine paused, searching her memory for the advice she had encountered in her own early days. ‘You must also be sure your thoughts are worth expressing,’ she added. ‘You need experience, my dear, and a fine education. Dabble in languages, hire a tutor for music lessons, study portraits and paintings, reflect upon the ideals of conversation and friendship. Have a romance, though don’t lose your head. Visit the opera and the theatre, the market at Les Halles. Then, you must mix it all into a great pot, cook your thoughts in the fire of your imaginings, hone them before a salon audience, where they must be presented prettily sugared and iced.’

She didn’t mention that in truth it would be best if the girl remained unmarried, that she avoided bearing children, in order to devote herself to sharpening her mind. That seemed unreasonable; by the time Marie Catherine had discovered her own talents, she had been firmly saddled with family.

Mademoiselle nodded, her eyes wide with enthusiasm.

‘Perhaps you might send me as story,’ suggested Marie Catherine. ‘I could arrange a recital for you, if I liked what I read.’

‘Oh, yes, thank you,’ said the girl. ‘And one more question. I don’t mean to be forward, but I must know what you’re working on now. When’s your new book coming? It’s been two horrid years since your fairy tales were published. Not that I grow bored re-reading them.’

‘To the contrary, she’d prefer to be curled up in front of the fire, reading,’ interrupted her mother. ‘I cannot convince her to take a walk.’

‘I’d rather be with your words,’ said the girl.

Marie Catherine twisted her signet ring. She looked carefully at the girl. ‘I’m afraid I cannot share any details with you. I’ve a horror of frightening away the muses. Just a little superstition of mine.’

Marie Catherine dared not admit that she had not produced an original sentence in months. When her former assistant, Monsieur Aragon, had suffered a sudden stroke, she had put her lack of inspiration down to the confusion around his death. But she had Angelina now, aptly taking on all his duties, and still she seemed stuck. All the advice and experience and practice in the world was not necessarily any help when one’s well had run dry of ideas. Glancing at the spirited conversations taking place at the tables in her chamber, she felt a desolate pain spear her side. What had happened to those hours she used to spend, wresting an idea that would not leave her in peace?

The fear rose, an overwhelming surge. If it were her last act, she would again seduce the gods of story to toss their net of wonders at her feet, to strew their gifts before her, and out she would pluck one starfish, one mushroom, one invisible cloak, one prince dressed as a pauper, one naked king. Oh, she would take it all and rush, her apron lifted and bulging with treasure, back to her desk to make sense of the hoard.