The road of malediction

Issue three: short fiction by Rebecca Anne do Rozario

Author’s note: ‘The road of malediction’ is inspired by d'Aulnoy’s Le Nain jaune, but turns upon the curious confusion between the French author and the English storytelling figure, and sometime ale wife, Mother Bunch.

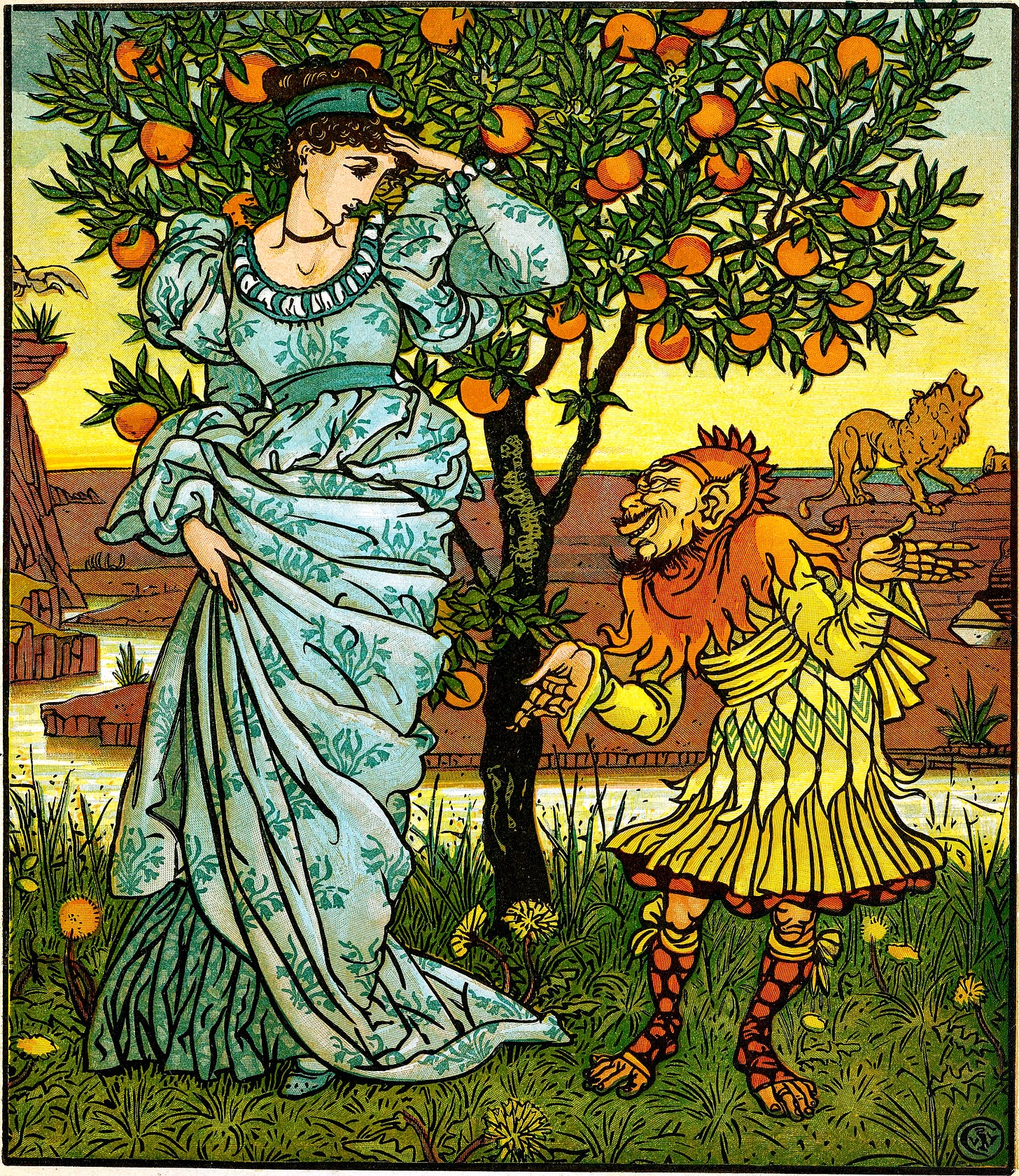

Granny opened the brown book. The pages were filled with damp, dust, and derring-do. The book had belonged to Granny’s granny and her granny before her. Before those grannies, no one could say for sure. It had been passed down from palsied to plump hand for many centuries, we thought, before our convict granny had even arrived in Australia. A revolting object, certainly, with mould and mouse-bitten corners, but my sisters and I curled up like puppies under our blanket, watching with wide eyes as Granny ran her fingers through the words of Mother Bunch’s Fairy Tales. Mother Bunch, she told us, had once been a glamorous French aristocrat, but grew old and wizened as her stories. We waited for her to announce the tale she would read to us. ‘The Story of the Yellow Dwarf,’ she announced. ‘There was a queen, who had but one daughter left alive, and she was indulged in all her wishes …’ She paused. ‘No, this is the stuff and nonsense of court. Tonight, I will tell the real history of Betty Bunch and the Yellow Gnome.’

At the end of the road of malediction, there is an orange tree. It grows in the courtyard of a pink limestone château. The château was once occupied by an ogre and his beautiful adopted daughter, Viola. It is now an interesting ruin and the young ladies of nearby Future Pinehollows visit with picnic baskets in the summer.

They never pick the oranges, although the scent is sweet, strong, and beguiling.

Today, the rain is pouring. Puddles grow on the flagstone floors. The moss and lichen on the walls darkens and grows as the limestone decays. There’s a tink of raindrops on metal in the kitchens. Someone left a pot on the stove and it has collected a soupy history of local precipitation and rodent bones. A muggy aspect rises from mouldering carpets in the great hall and the floorboards creak and crumble into dust. The branches of the orange tree are bare and disposed like lace against the sky, autumn’s foliage rotting beneath.

Betty Bunch placed her dagger in its sheath and stepped towards the tree. The hood of her scarlet cloak was pulled up over her bright silver hair. The weather made the curls effervesce about her cheeks. She wore high-topped boots, tan breeches, and a billowy shirt, embroidered in intricate patterns of green thread. Around her waist she had fixed a girdle fitted with sheathes and pockets for mysterious glass vials and uncomplicated weapons. On the crook of her arm, she carried a wicker basket covered over in a clean, red and white checked cloth.

Her tread was deliberate as she splashed straight through the pools of water that had formed on the ground, paying no attention at all to the care of her boots. She walked right up to the dormant tree and rapped her gloved knuckles hard against the trunk. Thrice.

Anybody might have said that the wind moaned in response. Betty tilted her head. She knew it as no idle wind. She rapped the trunk thrice more.‘Come on out, you old, bitter citron,’ she called. Her voice was robust with elegant inflections, which suggested she had grown up indiscriminately in ale houses and palaces.

A strip of tree bark shivered. It bulged forth, stepping from the trunk. The first part of anatomy to be distinguished was the interior of a cavernous mouth, edged with ill-tended teeth, the lips stretched out in a yawn and the uvula tickled. The yawn resolved into a gnome, skin like a dried-out bit of citrus, all desiccated, hard and pitted. A pair of bright yellow eyes gazed out.

‘Betty, my bosomy bride, what brings you to me li’l tree? Fancy a pleasurable dip in the conjugal waters?’

Betty closed her eyes, her features calm, and then twitched just the end of one finely drawn eyebrow. The gnome chuckled.

‘Well, then, me promised helpmeet, what is it you want of me? Although, I do wish you’d come in the spring, when I’m all plump and pithy. Ah, the times we’d have …’ He rubbed his hands in glee.

Betty gently tapped a foot.

‘You can’t, Betty. You can’t deny a man his nature.’

Betty spoke. ‘Scaring lasses out of their stays–that’s now an essential part of man’s nature?’

The gnome placed his fingertips where he imagined his heart might be. He was wide of the mark. ‘But I never spooked a lass in all my years, Betty. You know that. I only ever offer a way out of trouble. Trouble that comes with pointy teeth.’

Her hazel eyes sparkled at the latter remark. Once upon a time, she had been a lass herself. People had called her ‘Foxy Betty’ and were justifiably afraid of her wit, treating it like a roman candle freshly lit. And yet she had been flummoxed by a simple manoeuvre, a pick pocket’s sticky trick. Hence, her current dilemma in facing the gnome. Still, she owed a favour and she did at least know with whom she was dealing. ‘Not a lass this time, my sweet. A princess.’

‘A princess?’ He looked all about, as if expecting to see a marvel. ‘They go about on elephants, don’t they? Drip diamonds and rubies and pearls from their hair every time it gets a good combing? They wear whorled glass slippers that don’t smash during a hearty gavotte. And they make sport of old, ugly women and poor, revolting peasant boys. They spurt toads from their mouths when … no, no, I got that last bit wrong. What was it they belch?’ He was forced to pause as he dug about in his memory for more tittle-tattle.

Betty’s eyes betrayed a bone-weary acumen. ‘Those are all broken dreams, aspiration’s wreckage from past princesses.’ She listened intently to the other side of the falling rain. ‘You button that green waistcoat over a yellow belly,’ she said abruptly and turned.

‘You swore to wed me, Betty.’ His voice broke into a nasty slur.

Betty didn’t turn back, but her lips curled. ‘I didn’t say when, cur. Namby-pamby. Bully. I suspect you’ll find me quite, quite stiff by the time our wedding night arrives.’

From the broken down corners of the courtyard, veiled by drizzle and gloom, two sphinxes padded forward. Betty watched them apprehensively from within the vermilion protection of her hood. Their black locks were braided with shining pearls and leaves, delicate and veined, hammered from precious metals, and about their necks they wore collars of emeralds and citrines. Their faces were identically handsome and profusely freckled, though their grins revealed sharp teeth. Betty trembled like any reasonable woman.

The gnome watched, finding the sphinxes’ appetites repugnant, but wise to the potential in his situation.

Turning to her wicker basket, Betty slowly drew back the cloth, fingers apparently numb and arthritic.

You must bring cakes with which to feed the sphinxes that guard the way to the desert fairies, the lore informed all girls seeking a hot, dry fairy blessing. The sphinxes will spare you if you bring cake, but not if your basket is empty.

The lore had been recorded with peacock quill and turquoise ink by a brilliant authoress exiled by the Sun King. It helpfully included a receipt of millet seeds, powdered bonbons, and crocodile eggs. Betty had carefully followed the receipt that morning, gathering eggs from the crocodiles of the Misery Swamp, bonbons from the chef of the Carabas poet, and millet seeds from the enchanted bluebird daughters of the Merry-Begotten Warrior. The cakes had risen perfectly and she had sprinkled them with crushed golden toffee and warm cream skimmed from churns dangling on moonbeams in the night-time commons.

But now there were only crumbs in her basket. She tipped it over and the crumbs tumbled out, melting in the rain.

‘Oh dear,’ said the gnome with various counterfeit sighs. ‘You can’t have forgotten again, little Betty Bunch.’ He shook his charlatan’s head. ‘But I might be persuaded to hide you …’

Betty began to smile. She thought back to days when her hair was the brown of autumn birch leaves and her mind filled with the knowledge of falling stars and pale, benign moons. She smiled straight at the sphinxes, who were preparing to tear out her throat.

‘The cakes are in the pockets of his patched breeches,’ she said. ‘I have no objection to your plucking them out.’ Her hazel eyes were cool and shadowed as they shifted to the now terrified gnome. ‘Fool me once … and that’s it. Just the once.’ The hood fell back from her silver curls and she dropped the smile.

The sphinxes leapt past Betty, landing by the gnome. One licked his face from chin to receding hairline, a feline gesture, prickly and portentous. She found his sweat sour. The other bared her teeth and, though the gnome could not see her from behind his eyelids, he could feel her breath burning upon his hind quarters.

‘Oh, for Baba Yaga’s bristles! Betty, if you have compassion …’ He had never come so close to being consumed himself.

Betty let the moment wander in delight and then she wound it up with a short bark of laughter. ‘Ass. They won’t eat a rancid thing like you. Just give them the cakes and they’ll leave you be.’

Hand trembling, the gnome reached into his pockets and threw the cakes as far away as his momentarily atrophied muscles could manage. The sphinxes dove for their treats, playfully wrangling with each other as they disappeared back into the dry and draughty ruins. Later they would nuzzle and spoon.

‘Betty …’

‘And let that be an end to a trick that has served you well and dishonourably all these years. Do I have your consideration now?’

The gnome attempted to pull himself together. ‘Yes.’

‘I seek the Princess of Hearts. The heir to the throne. The only living daughter of the Great Queen of Joy. Her Highness Beauteous-Maxima.’ The fairies who had attended the birth of the princess had bestowed such beauty, grace, and wit as royal parents desired. Such foolishness results in silly names. Betty wondered why the fairies never tossed in a blessing for rude health, a gift for finding lost quills, or even the knack for baking delicious apple pies. Perhaps that was why she had never gone fairy godmothering, and why she had named her own child, found under a cabbage leaf, Barbara.

The gnome blinked, quite unaware of her inner monologue. ‘The Princess of Hearts came this way?’

‘She came seeking the fairies of the desert. I think it more than likely you stole her cakes.’

‘Well, I reckon the little lady is probably dodging a majestic loose fish or noble toadie. So I’m only assisting her.’

Betty drew a breath and let it out, much like a dragon lets out an initial volley of flame and sulphur. ‘You’ve stashed her, you hideous polygamist. And stop talking like a lawyer.’

‘You’re welcome to fetch her. She’s in the cosy bower that awaits even you, fairest Betty. And while a princess may be a jewel in my garden, may I say a tavern wench is a long, tall pint of ye olde fire water to a wee thirsty …’

Betty brushed him aside and regarded the tree, her hands on her hips. She grunted after a moment and removed a sodden, silver curl from her lower lip, where the rain had glued it. With a sure hand, she pulled down upon a low branch. It snapped in her fingers.

But it did not break off. There was a rasping and a groaning and the ground at the base of the tree split, revealing the pale, thready roots. Betty used the toe of her boot to displace a little dirt at the edge of the chasm, and peered down into the warm, brown earth.

The gnome reached into his pocket and withdrew an ancient pair of spectacles, the rims of twisted gold wire with milky glass lenses. He handed them to Betty. ‘You’ll need these.’

Betty was unperturbed. With nary a hesitation, she took a jump and descended down through the chasm, her feet and hands catching on the thirsty roots upon which the orange tree fed. They drew her down, down to where the gnome had made for himself a home, a canker, in fact, in mother nature’s fair complexion. Betty relaxed her grasp and allowed herself to free fall the last furlong, her red cloak fluttering up above her wild curls.

She landed softly on all fours. After brushing earth from her hands, she stood, aware of the sound of a shifting curtain and a turning lock. There was a shack in front of her, resting beneath a sky of moss and stalactites. It was low and rude, the timbers askew, the paint and plaster peeling and crumbling. A bright glow escaped the gaps in the walls and the fraying curtains at the windows. It was not a benevolent glow designed to guide wanderers home. There was a sharp, bitter edge to the light. It was a peasant’s torch flickering in a mob, the spark that lights a forest. Betty wrapped her cloak about her and took a step forward, allowing the very edges of the glow to touch her.

‘Please. Please don’t approach.’ The voice was brittle as a crazed porcelain plate and Betty sensed that a cruel word would smash it.

‘Are you Beauteous-Maxima, dearie?’ she asked, briefly stumbling on her words to imitate a trustworthy elder.

‘I was the princess,’ the girl responded. One quick rap and her voice would disintegrate altogether.

Betty took a gentle step towards the house. ‘Good. Good. Do you have need of comfort? Aid? I have nothing to sell you. No laces, stays, combs, or fruit do I peddle. It’s quite safe.’

‘Stop! Please. No closer … you mustn’t. I don’t want to hurt someone so venerable.’

Having recalled no warning of the princess’s violent proclivities towards the aged, Betty grew wary. ‘What do you mean?’ She turned around. ‘What does she mean?’

The yellow gnome was behind her. He was wearing a similar pair of spectacles to those he’d produced for her. Betty inclined her head and hooked the spectacles over her ears, pressing them into a comfortable position upon the bridge of her pert nose. ‘Princess, I’m guessing that you can come out now. Your itty-bitty husband is here with me.’

The door opened just a crack, releasing a little more of the light. It cut viciously through the gloom, radiating as the door opened. Through the thin circles of clouded glass protecting her eyes, Betty could see the fuzzy figure of the princess. She was tall and straight, her thick woollen travelling gown muddied at the hem, her long dark hair tangled upon her shoulders. Like most princesses, she was a nonpareil.

Her eyes, rather than her father’s cornflower blue or her mother’s nut brown, were molten fire. Betty promptly understood the glasses. Beauteous-Maxima’s eyes were twin suns in the dank underground.

The gnome’s expression was uncharacteristically solemn. ‘I swore to put the stars within her eyes,’ he said.

Betty stared hard at him. ‘Why would you do that?’

‘It was a chat-up line. I was trying to be charming, instead of plain loathly.’ He shrugged. ‘It was worth a try.’

A single tear fell from the princess’s left eye. It sizzled upon her cheek and dissolved into vapour, leaving a blister. Her lips twisted out of their bow into a ragged line of pain.

‘A chat-up line, I can understand,’ Betty remarked. ‘But to actually curse the poor child?’

‘Can you fix her?’

Betty twirled a silver curl around her finger. ‘This isn’t just a twinkle you put in her eye, but I can. However. There is much value in cracking a malediction.’ She smiled the smile of a pedlar who has magic trinkets in her basket.

The gnome was justifiably circumspect. ‘I have contemplated borrowing Goibhniu’s tongs to pluck the flaming eyeballs out, but,’ he paused just long enough to hear the princess’s gasp, ‘she’s a weedy thing and might perish during the operation.’

Betty grabbed him by the neck, catching his wiry beard quite deliberately, and lifted him from his degenerate patch of earth. ‘Do not tease the princess. If you tease her, I will kill you.’ She relaxed her grip and the gnome landed in a puff of dirt.

‘Kill me and you’d have to deal with the fairies of the desert. They’re me old cronies.’

Betty calmly removed a few brittle hairs from between her fingers. ‘Why do you think they live out in the desert, my repugnant one, far from your tree?’

The gnome rubbed his swelling neck and welted jaw and adjusted his waistcoat over his pot-like belly, full of acrid gases. He was beginning to revise his attitude towards matrimony. Indeed, it could be said he was actually moving with the times.

‘You want me to surrender my brides?’

Her response surprised his venal expectations. ‘No. For myself. Your claim is of no concern. I am never to honeymoon with you here below the orange tree. For the princess …’ Her gaze was fixed upon the girl. ‘For the princess, any deals are her business. I merely agreed to find her. I have done so. I will, however, set her loose and undo your attempt at inveiglement. Do not look so concerned, wrinkled milksop. You will not pay. That goes to the Queen of Hearts’ account.’ Betty indulged a sudden burst of laughter. It shook the mire from the walls and ceiling of the gnome’s holding.

A stalactite was ripped free and fell with a clatter and shuddering through the very centre of the shack, the debris imploding. Years after her death, people would know an earthquake as ‘Betty’s Chuckle’. ‘You have nothing to offer in settlement. Look about your domain. You do not reside in the ruins of an ogre’s estate. You do not even reside in the sweet perfume of an orange tree. You reside below, where worms and dung-loving beetles abide. hey are your lords and masters. The friendship of the fairies of the desert does not favour you well.’

The gnome was bereft of speech. Beauteous-Maxima's courage returned to her heart, however, and even Betty could hear it beat firm like a timpani drum.

‘You have come to help me?’

Betty poked her bright pink tongue out in a gesture of deep thought, her fingers prancing lightly over the vials and pouches upon her girdle. ‘Yes. What you need is an eclipse.’ Her fingers paused. ‘I was just visiting moonbeams this early morning. I wonder?’ She uncapped a vial of purple glass. The stopper gave a squeak as it came free. ‘Don’t flinch, Beauteous-Maxima.’ With a quick, supple motion of her wrist, she sprinkled a trail of dust in the princess’s face. The light faltered, devolving into brief flashes as it encountered each moonbeam speck. It was as if they were caught in the dying moments of a rocket display for the coronation of a new emperor, a gentle fizz and crackle stirring the air about them. As the spent dust settled, the princess raised her hands to her eyes and rubbed the last liquid jets of the twin suns away, revealing a cool sepia gaze. Her lashes were crimped by heat, her complexion fevered and peeling, but a crisp dignity returned to her posture and she set about regaining her natural autonomy.

‘Thank you, Betty. That’s much better. What shall we do about him?’ The slight emphasis the princess laid upon the last word evoked similar feelings for garden slugs and her favourite terrier’s turds.

‘Naught to be done,’ said Betty. She replaced the empty vial in its pouch. ‘He is undone by reality. I’ll give you a shove to get started, but you will have to climb the roots back to the surface yourself.’

Beauteous-Maxima’s smile was wide and white. ‘It will be a pleasure.’

The gnome remained below, sifting through the ashes of his self respect and the downfall of his connubial shack.

Betty hauled the princess up through the earth into the lengthening shadows of the interlaced orange tree branches and a lightening drizzle. She pulled up her hood and appeared determined to be on her way.

The princess stayed her with a light-fingered touch. ‘Betty, you know what my cause is. I admit this–predicament–was a miscalculation on my part, but …’

Betty allowed her hood to shift slightly back from her face. ‘You are very young. I know you seek to sabotage the fairies of the desert. You will seduce and betray their parched hearts with wine, women, and adolescent warblings about love. The Queen wishes to mistress their sandy domain. I have no problem with that.’

‘She told you?’

‘No, but I’m not a halfwit.’

‘You don’t care?’

‘I run a tavern, Beauteous-Maxima. Unless the desert fairies pay for good beer, they are not my concern.’

Beauteous-Maxima frowned, the future of sovereignty already giving her displeasure gravity. ‘And yet you took my mother’s commission?’

‘My prerogative and a favour returned. The desert fairies are that way. Nightfall is coming and you have many steps yet to take.’

Beauteous-Maxima vacillated only a moment, curious, but driven by other, more political concerns. She nodded and crossed the courtyard, disappearing through a pink wall brought down by a weight of jasmine blossom.

Betty Bunch stood a moment, half tempted to find an axe and cut down the orange tree. But as she breathed, the soft rain and the lingering citrus scent cleared her mind of malice, and so she located her basket and walked away. She whistled. It was a tune she had learned from the sirens, only harmless when she was quite alone. It drove the gnome, far below her path, quite mad.

The rain still falls. The puddles in the courtyard grow with the gentle plink plonk and the occasional run off from the remaining tiles that roof the château. The twilight is even now gathering in the windows, shadows of memory ready to spill as the day turns. There will be no more sun today.

Granny’s voice whirred and clanged to a standstill: a tale ticking to its end. She closed her strong front teeth and then snapped shut the book. ‘That’s enough dreams and conundrums for you to be sleeping upon,’ she said.

I waited for my sisters’ somnolent breath, a purr upon the pillows, and then I looked Granny in the eye. ‘That book was written by Betty Bunch, was it not?’

Granny was stroking our plain brown curls and I could see twinkles in her eye, moonbeam specks that could cool a million suns. ‘And what if it was?’

I drew in breath to speak an unutterable hope. ‘Are we descended from Betty? Did Betty herself pass the book into our family? Are the tales truly ours?’

Granny gently pressed me into the bed. ‘Oh, little one, you’re far too young to know. You must grow older, taller, rounder … and wrinkly like a great grey elephant. Make the most of your hopes and even more of your mistakes. And then you will know how to make a Betty Bunch tale.’

She kissed me quickly and wrapped me up in sheets and blankets alongside my sisters. Her joints knocked, her fingers shook. She faded into darkness, snickering.

Rebecca-Anne do Rozario has been a scholar of fairy-tales for many years, publishing widely in academic journals. Her book, Fashion in the fairy tale tradition: What Cinderella wore, was published by Palgrave in 2018. She has also published short fiction in magazines and journals including Gramarye, Aurealis, and Scheherezade's Bequest, and more recently published in the anthologies South of the Sun (2021) and Strangely Enough (2023). She currently works as a silversmith, living between Brisbane and her family farm on the Darling Downs.

This was a delight to read! :)

Loved this!