Water that does not gurgle

Issue seven: fiction by Jolie Toomajan

How thrilling to be bringing you a story from a writer with Armenian heritage drawing on her cultural roots with this retelling of the traditional tale of ‘The bride of the fountain’. The tale is one of many belonging to the ATU425 Animal as bridegroom group, which is often linked to Ovid’s ‘Cupid and Psyche’, and usually focus on a human bride married to a supernatural or animal groom. As Terri Windling notes, animal groom stories:

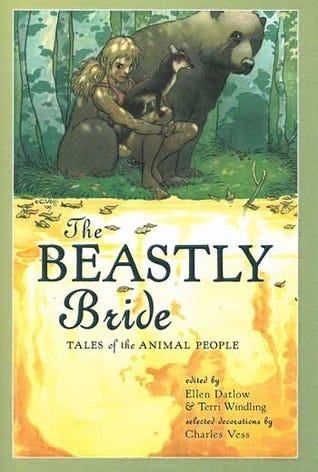

are steeped in an ancient magic and yet powerfully relevant to our lives today. They remind us of the wild within us...and also within our lovers and spouses, the part of them we can never quite know. They represent the Others who live beside us--cat and mouse and coyote and owl--and the Others who live only in the dreams and nightmares of our imaginations. For thousands of years, their tales have emerged from the place where we draw the boundary lines between animals and human beings, the natural world and civilization, women and men, magic and illusion, fiction and the lives we live (The beastly bride: tales of the animal people, edited by Ellen Datlow and Terri Windling, Viking, 2010).

We are grateful to our paying subscribers, who provide us with the means to keep publishing original stories, poems, and more. If you haven’t already, please consider signing up, or giving a gift subscription.

Usually, this story goes that the daughter is lost, with great sorrow, in some kind of slanted bet or devil’s deal. Not my darling youngest daughter, my snow-white rose, the pride of my home, my reason for being, please oh please anything but that. My mother still says it was accidental, that she stayed in the street rending her clothes and crying, Tush Tush Tush Tush, brood hen, egg master! She dove into the fountain headfirst and hit only concrete, so she dove again and again, scratched her fingers bloody. She told the neighbors she had to be torn away by the police, kicked and beaten with clubs.

My mother really gave me away so she did not have to buy a dress for me, having spent all her money on wool for my sisters. She dragged me to the fountain, called for him by name, and handed me to an elderly man. Have you ever been handed to someone like a plate of cheese and dolma, a thing to be transferred, the two of them maintaining eye contact over your head? I respectfully transfer this object to you.

The old man grabbed my biceps, falling backwards with me into the fountain, shoving water up my nose when my face hit the surface. It was all blue, and I realized, while I drifted downward surrounded by damp feathers, that I didn’t know where the blue of water comes from, why it disappears like a trick when you cup it in your hands. That was the last thought I had until I looked back to see my mother dusting her forearms. Straightening her cuffs.

The old man turned in the abyss, extended his neck like an anhinga, and pinched his fingers around my arm, yanking us deeper. I wasn’t scared, per se, being pulled down into the bluedark. I could never breathe in the dark, waiting for my sisters, for whatever they thought to do to me and how my mother would wave her hand and say pahel, keep it, and how my father would wave his hand and say pah-tah, nonsense sounds, and still my sisters would put needles in my face towels. That’s also the sound of the water as I pushed it aside, kicking and flopping. Pah pah pah pah. When the surface below us broke like a mirror, I found myself dangling from the old man’s hand like a hooked fish while he floated us to the ground.

In the chamber was a nest, a happy bowl made of karakul wool twisted into soft mounds. Smooth garnets adorned the rim, from which tassels of moonstone drops dangled like lures. And in the middle, the most beautiful man I had ever seen, beautiful like every bird at once. Everything feathered and hollow, buoyant and gravityless, swirled inside him. I saw myself as a happy red piece of meat in his talons, cradled and torn apart, and something inside me said oh.

The old man stepped back in deference, bowing. Following his gaze back to the eagleman gullman falconman caracaraman in the center of the nest, I was overwhelmed by the desire to put a leather hood over his head.

His mouth clicked open in delight. He gestured to the old man. ‘I didn’t think she’d give you to me if she thought you might be happy about it.’

Blessed, I thought. I have been blessed.

The walls of the chamber were dank, slightly clammy, with feathers stuck to them. My grousehusband sat, shirtless, on the back of the chair instead of the seat. He pulled a book from the pile on the desk and turned the pages too quickly to read them. He flapped a single page back and forth and smiled at the friendly wave that worked its way up the edge of the paper. When satisfied, he threw that book onto the floor and picked up another, gilt-edged, and fanned himself with it, delighted at the glittering.

I wiped my damp feet against my dress, pressing it into my shins, and picked my way over to the book on the floor (Healing), closing it and placing it on his desk. He snapped the book in his hands (Prosperity) shut like a beak , and I picked up the mug of his now-cold coffee. Three peas floated in the dark liquid.

‘Handsome,’ I said. ‘Having a good morning?’

‘My favorite shiny thing,’ he said. ‘Have you fed Father?’

‘Not yet. He’s still sleeping. I was hoping to spend some time in here, with you.’

‘Oh,’ he said. ‘Well. I’m pretty busy.’

‘You could let me help.’

‘No need, no need. Unlessl…’

‘Yes?’ I reached for him with the center of my chest. Tell me I’m worth it.

‘Let me teach you some things I’ll find useful. But I really want corn for dinner. With sunflower seeds? Can we have that? And then I’ll teach you?’

I looked at the peas suspended in the mug, and I saw possibility. The chamber was dark, but I could get candles. He spat seed shells onto the floor; I could sweep. I could cover the mirrors if he found himself too attracted to them, and, while I didn’t care for clutter, I could see that his valuables–the coins and bits of ribbon and torn apart flower petals–well, they had value to him, didn’t they? And therefore they had value to me. It was strange that when I startled him, he tilted his head and yanked one foot up off the floor, but was it truly more strange than the time my mother served everyone else a bowl of soup and me a bowl of broth?

It’s very simple. How much is freedom worth?

How far ahead can you see?

During my new life, I avoided the drinking fountains, not wanting to bump into a wandering dead or a stranger’s lips, both equally disturbing. I preferred the decorative fountains, where I drifted suspended in murky blue twilight, my outline invisible and impossible in the shifting waters, black hair blending into the concrete, gray dress waving with the light. I liked to float just out of view and watch the street dogs prancing in and out of the spray. Now and then, one of them would leap into the darker, deeper section of the fountain where I lurked, rippling, and give my face a pleased lick. Sometimes children cried Mama mama there’s a lady in the water, and the Mama always answered with something like Yes dear yes my darling love, and then Come, let’s get some apricots.

I liked the fighting the best. I interrupted family dramas, learned which houses had monsters, whose mother-in-law made dry lahmajun with too much lemon, whose husband preferred eating it that way (and insisted that his mother made it correctly). During one excursion, I encountered an arguing couple. The girl’s feet stuck out from under the hem of her skirt, dusty and strapped to the slat of a sandal with tiny chains.

‘I can’t go to the lake and play around. We have no clean towels, we have nothing to cook for dinner, nobody let out the dog before we left. This is all fun for you, but will you be washing the towels or picking up the dog shit? I won’t get to bed until after midnight,’ the girl said. She shifted her weight as she talked, the little chains on her feet glittering.

‘You never used to be like this; you used to be fun. Vibrant. Ever since I married you, you’ve slowly turned into your mother,’ he answered. Under the water, I covered my mouth with my palm.

‘If I’m turning into my mother, it’s probably because you’re acting like my father,’ she said, looking past him.

I huffed a laugh, producing tiny burbles.

I told this story to my shoebillhusband as I shook tossed coins from my tangled hair. ‘Isn’t that funny? Isn’t she quick?’

He rubbed the bridge of his nose while I talked.

Hm, he said.

Oh, he said.

Huh, he said.

Then he bundled me up in his overlong arms and deposited me in the nest, kissing the side of my neck before fluttering away over the rim, back to his work. A plate of dried fruit sat on top of a tiny woven rug. I sucked the sugar from fruits before falling asleep.

My mother eventually found me in the blasted shell fountain, the scooped one with the horizontal ribs mimicking the striations of a clam. I had seen my mother and sisters here and there over the last year: at the coffee shop reading cups, or shopping for walnuts and molasses. They tittered together, identical as nesting dolls. My mother never looked into the water, never drank from a memorial fountain, barely looked at what she left behind in the bathroom in the morning, so fearful was she of me jumping out of the toilet and accusing her with a pruny hand.

But this time, when water swayed over my eyes, the number of sisters changed as I looked, from two to four, then there were two mothers, then three. I drifted to the surface to get a better look and, when I did, my mother plunged her hand into the fountain and dragged me up by the soaking dress.

‘Is it true? You are married to the god of the fountain? I thought he made you a servant. Betrothed to a god and no favors for us?’

I sat silent.

‘I have rights as your mother.’

The right to hand me away. The right to love me the least.

‘Nothing to say for yourself?’

I opened my mouth and let a stream of water dribble down my body.

‘Tush!’

When my father-in-law appeared from the fountain, my mother released her grip on my dress.

‘I want the other one,’ my mother said.

My father-in-law stiffened. I could not stand the thought of her in my home, wriggling her bare toes on my dyed carpets, plucking up a stray feather and depositing it in the garbage while she clucked.

‘He does not take visitors,’ he said.

‘Then I want them to come and visit me. My daughter is a bride now; I deserve the honor of hosting the groom,’ she said.

‘Then I will have to send them,’ the old man said. He rubbed my shoulder encouragingly, looking down as I wilted under his hands. ‘It’s custom. It’s how it’s always been done,’ he said into the top of my head.

When I introduced my sisters, I wanted to say: These are my hot oil sisters, my sisters made out of piles of sewing pins. These are my acid-in-the-face sisters, my hairpulling sisters, my inhuming sisters, glue-trap sisters.

But I said, ‘These are my sisters.’

When I introduced my father to my husband, I wanted to say: Here is the stone that fills the room with its stillness. But I said, ‘This is my father.’

And when I introduced my mother, I wanted to say nothing, to let my face fall into a pleasant blankness, as if I addressed an elderly stranger. But I said, ‘And you’re aware of my mother already.’

The food, served when we arrived, consisted of olives and hunks of village cheese and bread laid on a freshly oiled plank. I had never gotten such treatment, and I watched jealously as my husband threw his head back and tossed olives into his open mouth, which he swallowed whole.

‘There are pits,’ I said. He ignored me. I thought about how easy it would be to burn this house to the ground in the middle of the night.

‘Enjoying the food?’ my mother asked.

‘Oh yes,’ he said, darting his head to bite at a piece of bread.

‘Perhaps you will allow us to visit our daughter next?’

‘Oh no,’ he said. I reached for the pomegranate seeds, intended to be garnish, and stuffed them into my mouth, bursting them with my tongue.

‘Why not?’ she pressed, and I thought Finally. He will condemn her, condemn them all for their treatment of me while I spit seeds into her decorative napkins. Somebody will name this madness.

‘I don’t like visitors. I’m very busy.’

I sucked the remaining seeds from my teeth and swallowed them.

‘In fact,’ he continued, ‘It is about time you show us to our room. One with a window, please. But take out the pane. I have the damndest time with those.’

In our room, peeling himself out of his shirt, he said, ‘They seem nicer than before.’

I heard Well, what did they do, force you to fill a bucket with blood every night? Enslave you to build a fountain large enough for a thousand birds? Task you with finding a single golden-headed fish in Lake Van? Tie you to a wild horse’s tail and drag you through the square? Turn you into a wooden block and toss you in the fire? I wanted to say yes to all of it, and add: they sold me to you.

When I was alone in bed that night, I thought that every family has a least favorite member, the one given the slice of pie that is mostly crust or the hunk of lamb that is mostly fat, the one destined to receive placeholder gifts picked up for some unspecified future occasion: soap, socks, a mug, cheese knives. I wasn’t unique in my misery, but that wasn’t the problem. I wanted it to make sense.

I wanted to be the least favorite because I was special and magical, because birds talked to me and rabbits fell at my feet, because I knew where all the herbs grew wild. I wanted to be the most beautiful, the one with sun-kissed skin and shiny black hair, the blackest eyes, the fullest lips, the longest and most prominent nose. The smart one who excels at everything, the one who can’t get away from books, the creative one, the artistic one, the clever one, the industrious one, the most hospitable to strangers. I even wanted to be a failure—a beautiful, skittering disaster—who burns the lavash and who can’t walk without tripping. The one with matted hair and a dirty, sandy face. The one who refuses chores. The one caught stealing dates from the grocer or secretly learning carpentry while she drinks the good brandy right from the glittering bottle. The kind of girl who earns a pelt.

I wanted a reason this had happened to me. Something to tumble around in my mind until the edges chipped away and I was left with a tiny, circular pebble. Neat, rollable.

The truth is, there is no reason. Cruelty is as random as anything else.

A razor hung taut on a piece of fishing line looks like nothing.

I will wonder for the rest of my life whether the razors were meant to slice into my eyes as I leaned on the sill to watch the heavy sky for my husband. Instead, I was oiling my hair when my partridgehusband flew through the window and cut himself to pieces. Over his cursing, I heard giggling at the door, and then rushing away. I had lived in the house long enough to recognize the sound of three sets of feet. My sisters had done this, but I knew where they got the razors.

My sparrowhusband lay curled at my feet, dribbling blood onto the floor. I reached for the carpet hanging on the wall to throw over him. Truth be told, I’d seen him in worse shape. He had a devil of a time with glass and still water, wind turbines, carts, and carriages. Once I pried him out of the jaws of a housecat (it was even wearing a bell; I don’t know how he managed). I knelt beside him, frustrated and sorry and horrified, and I expected him to say

Boy, they are pieces of work.

Jesus, you were right about your mother.

How did you survive these people?

Instead, he said, ‘How could you?’

‘What?’ I said. ‘How could I what?’

‘Why would you do this to me? Who would ever want such a bride?’

‘You think I–’

He cooed at me. He lay there like a fat little quail, and then he looked at me with his shining black-bead eyes and said, ‘Give me your blood, it will be faster. Remember what I taught you?’

I stepped over him, picked up his foot, and prepared to prick a hole in each finger with his little grey talons. I would massage his wounds with my bleeding fingertips to help him knit the skin back together. Healing him. That was one of the things I had learned.

I looked down at him, claw at the ready, and saw myself stealing his books in the night, leaving for the mountains, living alone with a big dog and a flock of sheep and every possible flower and herb. I saw myself living there for decades. I saw girls creeping up the mountain for my help, dragging incense offerings behind them. So many girls, dark-haired and sad-eyed, waiting at my threshold, blanketed in sweet-smelling smoke, all needing help. Standing over him, I invented them and then adopted them.

I released his claw. It curled under him when I stepped back. He sighed in irritation.

I saw myself on the mountain again. My hair will turn white as the arrowhead flowers strewn against the stones and grasses like freckles. I will keep my blood for myself.

Jolie Toomajan is a writer, editor, and all-around ghoul. Her work has appeared in Upon a thrice time, Death in the mouth, Apex, Remains, and Black static (among other places. She is the Shirley Jackson Award-winning editor of Aseptic and Faintly sadistic: an anthology of hysteria fiction. She has a PhD in English; her dissertation focused on the women who wrote for Weird tales. Despite all of this, she thinks the tapping sound on the window is probably nothing. You can find her anywhere @JolieToomajan

This was wonderful. So much sensory detail but it never weighed the whole thing down. The figure of the bird-husband was so striking.