Author interview: Melissa Ashley

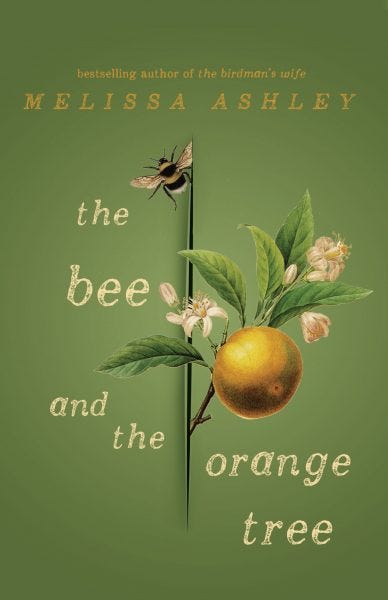

An interview with Melissa Ashley, the Australian author of the 'The bee and the orange tree', a work of historical fiction that centres on the life and work of Marie Catherine d'Aulnoy.

Melissa Ashley is the author of historical fiction novels The bee and the orange tree and The birdman's wife, which won the Queensland Literary Awards Fiction prize and the ABA Booksellers Choice Award. She has published a collection of poetry, The hospital for dolls, as well as short stories, essays and academic articles. Melissa is passionate about historical women's forgotten lives, particularly in science. Melissa's most recent novel is The naturalist of Amsterdam, which explores the life of entomologist and artist Maria Sibylla Merian's daughter Dorothea Graff. She lives in Brisbane with her family.

The orange and bee were delighted to have this opportunity to discuss writing and fairy tales with Melissa. And particularly thrilled to talk about the research and writing of The bee and the orange tree, a novel that imaginatively recreates the life of Marie Catherine d’Aulnoy, the French writer who coined the phrase contes des fées (fairy tales) to refer to wonder tales.

D’Aulnoy was an active and renowned participant in the French salon culture of the late 1600s, and hosted her own salon on rue Saint-Benoît, where she frequently performed her fairy tales prior to publication, sometimes while dressed as characters from the tales.

During her lifetime, d’Aulnoy published 25 fairy tales, and several volumes of fairy tales, including Les Contes des Fées, I–III (1696-97), Les contes de Fées, IV (1698), and Contes Nouveaux ou les Fées à la Mode, I–IV (1698). As Jack Zipes notes:

d’Aulnoy’s tales placed women in greater control of their destinies than they were granted in fairy tales by men … the narrative strategies of her tales, like those she told or learned in the salon, were meant to expose decadent practices and behavior among the people of her class, particularly those who degraded independent women (Zipes 2021, p. xvi).

O&B: A question that we want to start most of our interviews at The Orange and Bee with is asking about whether fairy tales have had a place in your life, in whatever form or shape you encountered them …

MA: Yes! Ever and always. As a girl I loved Hans Christian Andersen’s romantic and sentimental fairy tales ‘The Little Match Girl’ and ‘The Little Mermaid’. I have a memory of my Oma reading ‘The Little Match Girl’ to me and her being embarrassed but also kind, when I sobbed myself silly over the ending.

For half a decade I was obsessed with Angela Carter’s The bloody chamber (and her imagination and writing in general), and collected her compilation of world folk and fairy-tales, The Virago book of fairy tales and translations of Charles Perrault’s fairy tales. I don’t know why, but I have a push to read (or see films or art, not so much TV shows) as many different versions of a classic fairy tale that I like. I also really enjoy reading interpretations of a fairy tale’s meaning, across a range of disciplines. Many of them outdated but all very interesting as part of the conversation of understanding what they mean to us. Jungian, sociological, Freudian, post-structural, popular and so on. I love that there were taxonomists of fairy tale tropes, and those indexes of fairy tale types, the research is just so fascinating and cross-pollinating for my writing and imagination. I love Marina Warner’s From the beast to the blonde; Jack Zipes’s studies and collections; AS Byatt’s essays and revisions and modern fairy tales; Clarissa Pinkola Estes’s Jungian-themed Women Who Run with the Wolves. My 20s in the 90s: a kind of mytho-pagan-psychoanalytic-feminist arcadia.

O&B: What attracted you to writing about Baroness Marie Catherine D'Aulnoy?

MA: I was researching versions of the fairy tale ‘the girl without hands’ from all around the world and also reaching back hundreds of years, in both fairy tale and folktale versions. At the time I was doing an MPhil in creative writing and trying to write a contemporary novel, set in Brisbane, about this fairy tale. I had to write a critical essay on some aspect of my research and during my travels, found about the existence of The cabinet of fairies/Le Cabinet des fées published between 1785 and 1789, a forty-one volume compilation of French fairy tales collected by Charles-Joseph Mayer. It featured the work of Charles Perrault, who I knew, and the female French fairy tale authors: Marie-Catherine d’Aulnoy, Charlotte-Rose de Caumont La Force, Marie-Jeanne L’Héritier Villandon, and many more, all of whom I’d never heard of. I remember a very strong visual image I had of the 41 delicious volumes of fairy tales in lovely gilt and leatherbound first editions sitting on a library bookshelf like a treasure chest just waiting to be opened.

Marie Catherine d’Aulnoy has a fascinating backstory and I was immediately attracted to finding out more about her life and writing career: she wrote novels, memoirs, travel narratives and fairy tales. I experimented with a few short stories exploring the feeling of ‘discovering’ the Cabinet des Fées as a researcher, but it was only later that I thought of writing historical fiction about her.

O&B: Your novel, The Bee and the orange tree, opens in Paris in 1699, when France was under the rule of Louis XIV. D’Aulnoy is nearly 50 years old and, after many years of adventures, including scandals, exile, arrest, imprisonment, and a period of ‘solitude’ that lasted nearly ten years, she is comfortably ensconced in her home in the rue Saint-Benoît, where she has established her salon. Can you set the scene for us? What were the salons, and what role did they play in the society of the time?

MA: The French fairy tale golden age was the decade of the 1690s. From what I’ve managed to find out, they were inspired by a range of different narratives and texts: tales of chivalry and courtly love, classic myths, earlier published fairy tales like Giambattista Basile’s Tale of tales1, and even mother goose folktales, at least according to Charles Perrault.

The 1690s in France was a period of significant economic and political difficulty. Louis XIV’s ancien regime had been operating for decades and France was nearly bankrupted by incessant warfare with her neighbours. It was a particularly challenging time for women—I’m talking primarily about wealthy women—who had no financial independence, were forced into arranged marriages that moved money between families, and could not divorce or own property—a life they entered as young as fifteen. Amongst all this, a group of creative and brilliant women like Marie Catherine d’Aulnoy began holding literary salons in their private boudoirs. Here, women could gather in a luxurious spaces to share and circulate fairy-tale texts. It’s been suggested that the French fairy tale writers, the conteuses, used the tropes, symbols and archetypes of fairy-tale conventions to critique their social conditions and customs, and perhaps to inspire young women to use their imaginations to create a sense of agency (and escape) for themselves and in their lives.

Attendees of Marie Catherine’s salons would act out scenes in classic plays, participate in spontaneous writing games and exercises, recite and perform their stories and fairy tales and, also, circulate their manuscripts for feedback and critique. I loved this very modern-seeming element to their gatherings. As you can imagine, these games and performances, like any writing or creative ‘movement’ spurred and inspired all who participated to create and invent more and better stories and tales.

O&B: D’Aulnoy is perhaps best-known these days for coining the phrase contes des fées (fairy tales) to refer to the form also sometimes known as magic tales, or wonder tales. Why fairy tales? What other significant contributions did d’Aulnoy make to the history of fairy tales?

MA: Marie Catherine’s fairy tales were full of fairies and fairy worlds, often miniature courts, with tiny frogs, cats and birds as their main characters, rather than humans. And moats and castles and towers and dungeons: a pure delight. Marie Catherine also published the first fairy tale in France, L’Ille de la félicité (The island of happiness), which was enclosed inside a novel, the History of Hyppolite. Her fairy-tale collections had frame tales, following the tradition of Boccaccio’s Decameron.

There was a well-known society magazine Mercure Gazette, which published articles—a gold mine for the historical fiction writer—about the fashionable life for a woman of means. Issues of the Mercure Gazette contained book reviews, fashion and cosmetic advice, poems and short stories, advertisements for events and, following Marie Catherine’s debut publication, fairy tales. The publication of fairy tales in this journal launched a trend, and a thirst for this new genre among female readers, in particular. Later in the decade, Marie Catherine published her collections of fairy tales, alongside Charles Perrault’s Histoires ou Contes du Temps passé: Les Contes de ma Mère l'Oye (Tales and stories of the past with morals: Tales of Mother Goose). Renowned within France, Marie Catherine’s fairy tales are no longer very well known elsewhere, unlike Charles Perrault’s. There’s a range of reasons for this. One of the most interesting is that the Grimm brothers thought her work unrepresentative of the typical fairy tale because her stories were baroque in style, ornate and intricate, rather lengthy, and perhaps not intended for a children’s readership.

O&B: Your other novels—The birdman’s wife (2016) and the more recent Naturalist of Amsterdam (2023)—are also works of historical fiction that focus on the lives of real historical women. Are there other ways that The bee and the orange tree is like your other books?

MA: The Naturalist of Amsterdam and The Bee and the Orange Tree are both set during a similar time, the late 17th and early 18th centuries, during the long transition from the Early Modern period to the Enlightenment, when the intermingling boundaries between art and science were dissolving and regrouping. All three of my protagonists made significant contributions to their professional fields, but, apart from specialists such as academics, are not well known. I want to challenge some of our myths about women’s (lack of) contributions to art and science. Dig a little and there’s a woman, filed under her husband’s or tutor’s name; her inventions or insights stolen. Who doesn’t want to hear about these lives? All my protagonists were well-known during their lifetimes, enjoying fame and success, but for a range of reasons, their achievements were forgotten (or suppressed) after their deaths. Something else my protagonists’ lives have in common is that they were all involved in the business of writing, making, publishing and distributing books. This hasn’t been consciously intentional but I really like that connection.

O&B: In what ways is The bee and the orange tree unlike your other works?

MA: The Bee and the orange tree takes place over a three-month period and explores d’Aulnoy’s possible involvement in an attempted murder. It’s a crime story, narrated by three different voices, whereas my other historical fictions are about naturalists. The Birdman’s Wife is about Elizabeth Gould, a bird artist and lithographer, wife of John Gould, Australia’s ‘birdman’. The Naturalist of Amsterdam is the story of Dorothea Graff, the daughter of Maria Sibylla Merian, the very first ecologist and an entomologist, botanist, artist, and publisher. Both women were mothers and both undertook extremely risky scientific ventures to complete the research for their professional work. Both these female naturalists’ stories centre around the creation and publication of their most important works: The Birds of Australia in the case of Elizabeth Gould and The Metamorphosis of the Insects of Suriname in the case of Dorothea Graff and Maria Sibylla Merian.

O&B: One of the most quietly thrilling aspects of this book is its focus on women’s friendships. There’s an interesting connection here to traditional fairy tales, which are so often focused on women and girls. How important was it for you to write about female friendship and collaboration in this book? Do you think that these images you’ve created—of women banding together to protect and support each other—is true to the historical characters? Are there limits to the political and social value of d’Aulnoy’s (real or imagined) friendships with other women?

MA: Oh, thank you, that’s so great to hear. The female friendships between the conteuses—they also wrote poems, plays, novels—were utterly central to my desire to write The Bee and the Orange Tree. I found the space of the salon—this private place where intellectuals, influencers, creatives, court figures, social climbers, and their sophisticated hostesses gathered to entertain one another and be entertained—enticing and fertile as a setting. I felt the modernity of the salons could reflect contemporary readers’ engagement with literature and authors through festivals, workshops, and private writers’ groups.

I researched the conteuses lives and strove to represent the intersection of their paths with the historical record as closely as possible. Questions about female friendship, and collaboration and collegiality, have become increasingly important to me in thinking historically about barriers to women’s advancement in various professions. The importance of female friendships, their support and competitiveness, the dynamism of their writing circles and social settings, was absolutely fundamental to the abundance of tales and collections that d’Aulnoy and the other conteuses wrote and published. Connected to considerations of women’s professional friendships was the notion of a female canon: the lineage of French female authors that brought the conteuses to this point in history. The conversations between the work of the conteuses of the 1690s and the work of earlier generations of French novelists like Mademoiselle de Scudery and Madame de la Fayette informed them and contributed to their achievements.

O&B: One of the challenges of writing historical fiction about real people is deciding how faithful to be to the known facts, and how much liberty to exercise in imagining into the gaps. Can you speak a little about your own approach to these aspects of writing historical fiction?

MA: It is an endless question for every historical fiction author. It’s a conundrum for me and relates to the historical record, what research has been undertaken and how extensive the archive is. With Marie Catherine, there was limited material about the conditions of her private life. Some of the sources provided contradictory accounts of the countries she lived in, whether she was jailed or lived in a convent, so I had to decide how to interpret the experts. On the other hand, the sheer volume of writing she published, and the academic engagement with it, was completely overwhelming. Marie Catherine was involved in several crimes, so there was an administrative and newspaper archive to explore too.

In imagining Marie Catherine’s experiences, I tried not to change the agreed upon facts among sources and their interpreters. However, where there were discrepancies, I made my own interpretations, both to serve the demands of the narrative, and to reflect what might have happened. The pleasure in writing (and reading) historical fiction is delving into the interiority of your protagonist to explore their motives, their emotions, their loyalties and values.

I’m writing my fourth work of historical fiction and this question continues to trouble me and to evolve in meaning. It’s got a practical side, in that actual experiences don’t fit neatly into the way a novel is structured, nor does narrative drive invent itself. In my most recently published novel, questions of fact and fiction were pulled apart and I had to ask myself what I wanted to say about my character. Why did I want to tell her story?

The protagonist of the novel I’m now writing (an anatomist and wax modeller) has a fabulous feminist narrative arc, but there are materials in her life and her colleagues lives in the archive that I cannot access—and do not want to access—I’m writing a novel, not a biography. So, there are lots of decisions to be made about how I get across the spirit or essence of who she was and the period in which she lived. I have to find the best example from her life, the thing that happened, which best shows this.

No novelist agrees on the answers to this question, it seems. Colm Tobin has written about Henry James, Coetzee about Jesus Christ. AS Byatt, one of my favourite novelists, is on the record as saying one should not write about real lives, one must always invent. And there’s Zadie Smith, who spoke in an interview recently about her historical novel The Fraud, and how readers rush off to Google any questions that arise as they read, so a novelist might take this into account when writing. What to include, what to leave out.

And at the end of the day, historical novelists have the author note or foreword to justify and explain various decisions taken, as well as that very important little noun— fiction—for protection.

O&B: In 2017, you were awarded a three-month residency in Paris by the Australia Council to work on The bee and the orange tree. Can you talk about your experience of working on this book while living in Paris?

MA: It was an incredible experience and privilege to live near Marie Catherine’s various neighbourhoods and to wander the streets she had travelled, to see the skyline that was hers and to visit the many palaces, churches, homes, and interiors that had been preserved or restored to their condition in the time of Louis XIV. I really loved exploring museums that had collections of costumes, that had room after room of historically accurate interior décor, design, and architecture, and, of course, studying the paintings and art of the time that, as a novelist, are some of the most important historical texts.

I stayed in an international arts residency, with hundreds of practitioners from all over the world practicing every area of art, music, and literature imaginable. There were modern-day salons, among a small group of artist-friends, and open-door exhibitions every night, when an artist would put on wine and cheese and open their studio to anyone who’d like to see their works in progress. It was lucky for me that the default language of the residency was English. I did some French language courses, but all but gave up during my time there. I remember going to see an interview with Paul Auster, with a group of Australians, and how silly we felt listening to an interview conducted entirely in French. (What were we imagining?) I remember snow, jazz clubs, kirs, the beauty of a modest bouquet of ranunhospitaculus and peonies on my writing desk, galleries, parks, blankets on laps and touching elbows with my fellow diners. I’ve recently been to Italy for my latest novel and as I wander through my day’s creative thoughts and work, I’m there walking the streets of the city I visited. I remember feeling that I wanted to stop time, that the rich experiences were running through my fingers. But then you get to go home and re-experience it over and over again during the writing process.

O&B: I’m sure that, when you aren’t fortunate enough to be on a residency, you have to do the tough work of balancing your writing and your other work and responsibilities. What does that look like for you? What strategies do you use to protect or nourish your writing practice?

MA: Once upon a time I had a variety of writers’ groups, as well as university mentoring, where I spent lots of time circulating my work amongst other trusted readers and professionals—and returning the favour, of course—but when I published my first novel, that process changed slightly. I didn’t want so many eyes on my work, as inevitably certain things are subjective, and so I had my agent and publisher, editor, a couple of trusted beta readers, to give me feedback. How does this relate to my process? In the last year, I’ve joined a virtual writing group. We don’t read each other’s work, but we meet up twice a week and check in, letting each other know what our plans are for the day, going off and writing, and then checking in again. Some of us meet every morning (for about 20 minutes) and its extremely helpful in keeping me inside the day to day drafting of a book.

This group has been game changing. I’ve spent (far too much) time isolated as a novelist. I research quite heavily, and my writing is generally quite slow. My last book took a year longer than I had planned to finish. But now I feel like I have colleagues, that I’m not alone, and that my typical experiences—being stuck, wanting to run away to the shops or the movies, procrastination, anxiety, a sudden breakthrough: ah, that’s how it works! it’s not so hard!—and so on, are shared. I’ve just finished a first draft and during this process I really need to get stuck in and pretty much write six days out of seven. It may be for one hour or five hours, but I have to turn up day after day. I think it’s the most crucial element of this stage in writing a novel. If I start taking breaks, I pull out of the work, I drop the stitch or lose the thread, and it can take me days and much frustration and guilt, trying to get settled back in again. It’s different when I have a draft to shape up, revise, or edit. I can do that more easily around other work and family commitments. I can sustain it for much longer stretches of time. Writing a first draft, making something out of nothing, is exhilarating, a reason to get up and live, but it’s also mentally intense, both emotionally and in the sheer effort of flexing one’s brain so hard. But once it’s out of the way, there’s a great relief and the knowledge that I can go back and shape the pile into what it’s meant to be.

O&B: You are an experienced and well-respected writing teacher. This year, for example, you’ll be teaching the Queensland Writers Centre’s Year of the Novel program. How do you approach the challenge of teaching writing?

MA: I over-prepare, armed with five times more resources that I’ll need. But that’s ok. Although I’ve published several novels, I sometimes feel like I’m back at square one with every new book. I’ve been teaching for some time, and I feel that now, I’m getting more out of teaching than ever before, learning more from my students about the techniques and devices we use to create stories.

One of the best things about being a novelist is that you never run out of problems and challenges. Problem-solving, adaptiveness, and patience are so important, and its great being in a room full of people studying a bunch of texts to see how different writers do the essentially same thing—invent and construct narratives, tell stories—in so many varied and wonderful ways.

A big part of writing courses for me is giving students confidence to step into their own creativity, to let it out onto the page before shaping or critiquing it. It’s so important to make the writing situation pleasurable, and I think it’s good to give students a range of tricks and practices they can use to switch into a creative headspace—flow, the zone, whatever people call it—and start to dig into their own imaginations. Writing a novel is generally a work of solitude and so I emphasise the psychological side of creativity: being kind and compassionate to oneself, being patient and turning up, sitting with uncertainty, all important qualities for getting through to the end of drafting a long work.

I recently went on a retreat with printmakers and other visual artists, and I was struck by how process-focused making visual art is. The fact that the artist doesn’t necessarily know how a technique or an application will turn out, and how that’s all part of the process, the fun. Its handy to bear in mind for a writer: to release that imperative to get to the end of the sentence, paragraph, chapter, draft, which can become a little suffocating, and where’s the pleasure in that?

O&B: Before the breakthrough success of The Birdman’s Wife (2016), you were perhaps better known as a poet. I remember your collection The hospital for dolls, which came out in 2003, whose first poem begins with a powerful image of the blind giant tying on his boots.

The blind giant tied on

his boots, unfolded his

stick and strode through

the bitumen black to

ignite the stars.

The moon came on

like an obscene dancer,

shedding clouds like clothes

on the floor of the sky.

I can’t help but notice the fairy-tale nature of that opening image. And other images from the collection, too, seem haunted by the spectre of fairy-tale beings and spaces, like the image at the end of the same poem, of a baby laid down to rest ‘in a bed of glass / a bed of stone’. Do you feel that starting out as a poet has had a significant impact on your approach to writing?

MA: Yes, I think it has. It could also by my visual imagination, and my desire to reduce things down to their basics. Elements. I love myths, too. I was always looking for answers, theories, philosophies as to why we act in the way we do, why we have complexes and hang-ups, obsessions and Freudian neuroses—this is back in my 20s— and all of that informed the way my mind engaged with fairy tales and questions of creativity. That’s when I was a poet. Poetry is a compressed, symbolic language, just like the fairy tale, like Freud’s unconscious (I’ve gone back to the 90s), which is supposedly structured like a poem. But perhaps that’s why the French conteuses used fairy tales: to express the inexpressible, to use a shorthand symbolic archetype or trope to critique an injustice in an oblique fashion. Just as poetry uses metaphor. I can’t help but linger on the beauty of a place or setting, its smell and its colours, although perhaps I should get on with telling the story.

O&B: Finally, do you have a favourite fairy tale? What is it about that particular fairy tale that resonates with you, or has been important for you?

MA: It’s so hard to pick just one! The Girl Without Hands is the fairy tale that I have engaged with on the deepest level over a life of loving fairy tales and their archetypes being fundamental to my imagination. But that may now have been replaced by AS Byatt’s version/translation from the French of Marie Catherine d’Aulnoy’s ‘The White Cat’, for which she’s best known.

References

Zipes, J (trans.) 2021, The island of happiness : Tales of Madame d’Aulnoy, Princeton UP, New Jersey.

Lo cunto de li cunti overo lo trattenemiento de peccerille (The tale of tales, or entertainment for little ones), published posthumously in two volumes (1634 and 1636) by Basile’s sister, Adriana, under the pseudonym Gian Alesio Abbatutis.

Hi Mamma Yaga, I'm glad you liked the interview. The book the translation comes from is 'Wonder Tales: Six French Stories of Enchantment' edited by Marina Warner. My copy is hard cover and the book itself is a small, squarish format. It was published in 1996. I love it, I'm sure there's a copy floating about somewhere.

Hi. Lovely interview. I admire everyone's work here including Melissa Ashley's vision which shone through this piece. I was not able to find a source for "AS Byatt’s version/translation from the French of Marie Catherine d’Aulnoy’s ‘The White Cat’, for which she’s best known." Where might I read that version?