Brothers Grimm's Maid Maleen

A traditional tale, with a brief introduction, discussion questions, and a writing prompt

In this issue of The Orange & Bee, we are exploring ‘Maid Maleen,’ which was first published as ‘Jungfer Maleen’ by Karl Müllenhoff in Sagen, Märchen und Lieder der Herzoghümer Schleswig, Holstein und Lauenburg (1845). Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm were aware of this story—Müllenhoff had been Wilhelm’s student—and acknowledged this literary source in their notes for their own version of the tale, writing: ‘This is an excellent tale, both as regards matter and completeness. The oft-told recognition of the true bride is beautifully described’ (qtd in Hunt). The Grimms added the tale to the second volume of the sixth edition of the KHM, which was first published in 1850. According to Katherine Langrish, the Grimms added depth to the trauma caused Maleen’s abandonment and interment in their variant.

Introduction to the Brothers Grimm Jungfrau Maleen (Maid Maleen)

‘Maid Maleen’ is an example of tale type ATU870 The princess confined in the mound, which falls within the range of realistic tales (850 to 899) within the Aarne-Thompson-Uther Index (ATU Index). Interestingly, these tales fall outside of the range of tales of magic (fairy tales!). There is one sub-variant of ATU870, which is ATU870A the goose girl (neighbour’s daughter) as suitor (previously described, in the AT Index, as The little goose girl).

Examples of ATU870 tale type include:

‘The princess who was hidden underground’ translated from German and collected in Andrew Lang’s The violet fairy book (1901).

‘Die Gänsemagd’ (The goose girl) collected by Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm, and included in their Kinder- und Hausmärchen (Children’s and household tales), first published in 1816 as #89). An English translation of the Grimms’ ‘The goose girl’ was also included in Andrew Lang’s The blue fairy book (1889).

‘Vesle Åse Gåsepike’ (Little Annie the goose-girl) was collected by Peter Christen Asbjørnsen and Jørgen Moe in Norske folkeeventyr (Norwegian folktales), published between 1842 and 1852. And English translation—‘Little Lucy Goosey Girl’—was included in Reidar Thorwalf Christiansen’s Folktales of Norway (1964).

‘Destined girl wins her place as the prince’s bride’ was collected by RM Dawkins in Modern Greek folktales (1953).

Like many traditional fairy tales, ‘Maid Maleen’ focuses on the female protagonists’ loyalty to her beloved through significant trials and suffering, and over many years.

Maid Maleen: story and annotations

‘Maid Maleen’ was translated (and edited) by Margaret Hunt for an English edition of Jacob and Wilhelm Grimms’ Household Tales first published in 1884. You can find a digitised version of this translation at SurLaLune. For those of you seeking a print copy, or a translation that is more faithful to the Grimms’ version, Jack Zipes included a new translation of ‘Maid Maleen’ in The original folk and fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm: the complete first edition (2014).

There was once a King who had a son who asked to marry the daughter of another mighty King. She was called Maid Maleen1, and was very beautiful. As her father wished to give her to another, the prince was rejected; but as they both loved each other with all their hearts, they would not give each other up, and Maid Maleen said to her father, ‘I can and will take no other for my husband.’

Then the King flew into a passion, and ordered a dark tower2 be built, into which no ray of sunlight or moonlight should enter. When it was finished, he said, ‘Therein you shall be imprisoned for seven years3, and then I will come and see if your perverse spirit is broken.’

Meat and drink for the seven years were carried into the tower, and then Maid Maleen and her waiting-woman were led into it and walled up4, and thus cut off from the sky and from the earth. There they sat in the darkness, and knew not when day or night began. The King’s son often went round and round the tower, and called their names, but no sound from without pierced through the thick walls. What else could they do but lament and complain?

Meanwhile the time passed, and by the diminution of the food and drink they knew that the seven years were coming to an end. They thought the moment of their deliverance was come; but no stroke of the hammer was heard, no stone fell out of the wall, and it seemed to Maid Maleen that her father had forgotten her. As they only had food for a short time longer, and saw a miserable death awaiting them, Maid Maleen said, ‘We must try our last chance, and see if we can break through the wall.’5

She took the breadknife, and picked and bored at the mortar of a stone, and when she was tired, the waiting-maid took her turn. With great labour they succeeded in getting out one stone, and then a second, and a third, and when three days6 were over the first ray of light fell on their darkness, and at last the opening was so large that they could look out.

The sky was blue, and a fresh breeze played on their faces; but how melancholy everything looked all around! Her father's castle lay in ruins, the town and the villages were, so far as could be seen, destroyed by fire, the fields far and wide laid to waste, and no human being was visible.

When the opening in the wall was large enough for them to slip through, the waiting-maid sprang down first, and then Maid Maleen followed. But where were they to go? The enemy had ravaged the whole kingdom, driven away the King, and slain all the inhabitants. They wandered forth to seek another country, but nowhere did they find a shelter, or a human being to give them a mouthful of bread, and their need was so great that they were forced to appease their hunger with nettles7. When, after long journeying, they came into another country, they tried to get work but wherever they knocked they were turned away, and no one would have pity on them. At last they arrived in a large city and went to the royal palace. There also they were ordered to go away, but at last the cook said that they might stay in the kitchen and be scullions8.

The son of the King in whose kingdom they had arrived was the very man who had wanted to marry Maid Maleen. His father had chosen another bride for him, whose face was as ugly as her heart was wicked. The wedding was fixed, and the maiden had already arrived. Because of her great ugliness, however, she shut herself in her room, and allowed no one to see her9. Maid Maleen had to take her her meals from the kitchen. When the day came for the bride and the bridegroom to go to church, she was ashamed of her ugliness, and afraid that if she showed herself in the streets, she would be mocked and laughed at by the people.

Then said she to Maid Maleen, ‘A great piece of luck has befallen you. I have sprained my foot, and cannot well walk through the streets; you shall put on my wedding-clothes and take my place; a greater honour than that you cannot have!’

Maid Maleen, however, refused, and said, ‘I wish for no honour which is not suitable for me.’

It was in vain, too, that the bride offered her gold. At last she said angrily, ‘If you do not obey me, it will cost you your life. I have but to speak the word, and your head will lie at your feet.’

Maid Maleen, thus forced to obey, put on the bride's magnificent clothes and all her jewels. When she entered the royal hall, everyone was amazed at her great beauty, and the King said to his son, ‘This is the bride I have chosen for you, and whom you must lead to church.’

The bridegroom was astonished, and thought, She is like my Maid Maleen, and I should believe that it was her, but she is either still shut up in the tower, or she is dead.

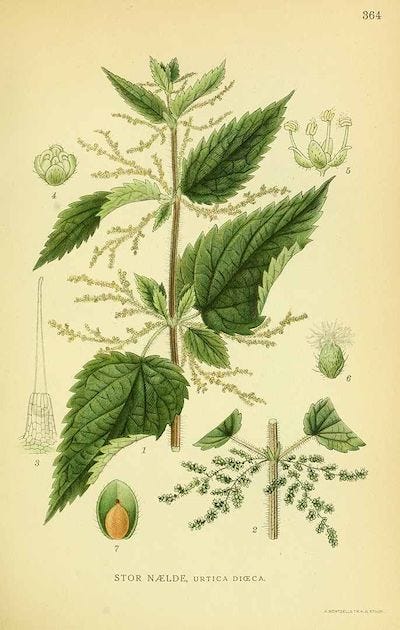

He took the bride by the hand and led her to church. On the way was a nettle-plant1011, and she said:

‘Oh, nettle-plant,

Little nettle-plant,

What dost thou here alone?

I have known the time

When I ate thee unboiled,

When I ate thee unroasted.’‘What are you saying?’ asked the King's son.

‘Nothing,’ she replied. ‘I was only thinking of Maid Maleen.’

He was surprised that she knew about her, but kept silence. When they came to the footbridge12 into the churchyard, she said:

‘Footbridge, do not break,

I am not the true bride.’ ‘What are you saying there?’ asked the King's son.

‘Nothing,’ she replied. ‘I was only thinking of Maid Maleen.’

‘Do you know Maid Maleen?’

‘No,’ she answered. ‘How should I know her? I have only heard of her.’

When they came to the church door13, she said:

‘Church door, break not,

I am not the true bride.’‘What are you saying there?’ asked he.

‘Ah,’ she answered, ‘I was only thinking of Maid Maleen.’

Then he took out a precious chain, put it round her neck, and fastened the clasp14. Thereupon they entered the church, and the priest joined their hands together before the altar, and married them. He led her home, but she did not speak a single word the whole way. When they got back to the royal palace, she hurried into the bride’s chamber, put off the magnificent clothes and the jewels, dressed herself in her grey gown, and kept nothing but the jewel on her neck, which she had received from the bridegroom.

When night came, and the bride was to be led into the prince’s apartment, she let her veil fall over her face, that he might not observe the deception. As soon as everyone had gone away, he said to her, ‘What did you say to the nettle-plant which was growing by the wayside?’

‘To which nettle-plant?’ asked she. ‘I don't talk to nettle-plants.’

‘If you did not do it, then you are not the true bride,’ said he.

So she thought to herself, and then said, ‘I must go out unto my maid, who keeps my thoughts for me.'

She went out and sought Maid Maleen. ‘Girl, what have you been saying to the nettle?’

Maid Maleen replied, ‘I said nothing but:

Oh, nettle-plant,

Little nettle-plant,

What dost thou here alone?

I have known the time

When I ate thee unboiled,

When I ate thee unroasted.’The bride ran back into the chamber, and said, ‘I know now what I said to the nettle,’ and repeated the words which she had just heard.

‘But what did you say to the footbridge when we went over it?’ asked the King's son.

‘To the footbridge?’ she answered. ‘I don't talk to footbridges.’

‘Then you are not the true bride.’

She again said, ‘I must go out unto my maid, ho keeps my thoughts for me,’ and ran out and found Maid Maleen. ‘Girl, what did you say to the footbridge?’

Maid Maleen replied, ‘I said nothing but:

Footbridge, do not break,

I am not the true bride.’‘That costs you your life!’ cried the bride, but she hurried into the room where the bridegroom waited, and said, ‘I know now what I said to the footbridge,’ and she repeated Maid Maleen’s words.

‘But what did you say to the church door?’

‘To the church door?’ she replied. ‘I don't talk to church doors.’

‘Then you are not the true bride.’

She went out and found Maid Maleen, and said, ‘Girl, what did you say to the church door?’

Maid Maleen replied, ‘I said nothing but:

Church door, break not,

I am not the true bride.’‘That will break your neck for you!’ cried the bride, and flew into a terrible passion, but she hastened back into the room, and said, ‘I know now what I said to the church door,’ and she repeated the words.

‘But where is the jewel I gave you at the church door?15’

‘What jewel?’ she answered. ‘You did not give me any jewel.’

‘I myself put it round your neck, and I myself fastened it; if you do not know that, you art not the true bride.’ He drew the veil from her face, and when he saw her immeasurable ugliness, he sprang back, terrified, and said, ‘How did you get here? Who are you?’16

‘I am thy betrothed bride, but because I feared the people would mock me when they saw me out of doors, I commanded the scullery maid to dress herself in my clothes, and to go to church instead of me.’

‘Where is the girl?’ said he. ‘I want to see her. Go and bring her here.’

She went out and told the servants that the scullery maid was an impostor, and that they must take her out into the courtyard and strike off her head. The servants laid hold of Maid Maleen and wanted to drag her out, but she screamed so loudly for help, that the King’s son heard her voice, hurried out of his chamber, and ordered them to set the maiden free instantly. Lights were brought, and then he saw on her neck the gold chain which he had given her at the church door.

‘You are the true bride,’ said he, ‘who went with me to church; come with me now to my room.’

When they were alone, he said, ‘On the way to the church you spoke of Maid Maleen, who was my betrothed bride; if I could believe it possible, I should think she was standing before me—you are like her in every respect.’

She answered, ‘I am Maid Maleen, who for your sake was imprisoned seven years in the darkness, who suffered hunger and thirst, and has lived so long in want and poverty. Today, however, the sun is shining on me once more. I was married to you in the church, and I am your lawful wife.’

Then they kissed each other, and were happy all the days of their lives. The false bride was rewarded for what she had done by having her head cut off.

The tower in which Maid Maleen had been imprisoned remained standing for a long time, and when the children passed by it they sang17:

Kling, klang, gloria.

Who sits within this tower?

A King's daughter, she sits within,

A sight of her I cannot win,

The wall it will not break.

The stone cannot be pierced.

Little Hans, with your coat so gay,

Follow me, follow me, fast as you may.Discussion questions

Maid Maleen is far from the only figure from folklore and fairy tale to be imprisoned in a tower. One of the most familiar to contemporary readers is Rapunzel (ATU 310 The maiden in the tower). In Rapunzel’s case she is locked away as a possession to be protected, whereas Maid Maleen was entombed as a punishment for disobeying her father. Maid Maleen embraces love over parental acceptance. She rejects her prescribed role as an object to be bought and sold. The imprisonment of women for refusing to marry can also be seen in depictions of the lives of saints. For instance, Saint Barbara was imprisoned in a tower by her father to keep her safe from suitors and Saint Catherine was locked away by her father when she refused a royal marriage. What role does this imposed isolation by a parental figure play in the development of fairy tale heroines? Can a character take an active role in their own story when confined by such physical restraints?

When Maid Maleen finally finds herself working in the kitchen of the court of her prince, she discovers that he has been betrothed to another woman. Chosen by the king, this false bride is described as ugly and wicked, two characteristics commonly attributed to female, fairy-tale antagonists. Ashamed of her ugliness, she forces Maid Maleen to attend the wedding in her stead. On her way to the chapel, Maid Maleen disavows herself as the true bride. Katherine Langrish writers that ‘She is afraid that the honest world will reject her, the foot-bridge break under her step, the church door split as she passes through … In Maid Maleen, the heroine and the false bride mirror one so another so strikingly in their low self-esteem, that on a psychological level the ugly false bride may even be Maid Maleen’ (Langrish 2019). How does the complexity of trauma (abandonment, isolation, and poverty) enhance the disassociation experienced by Maid Maleen? How might this parallel the false bride’s concerns with forced marriage, social estrangement, and/or fear of rejection?

This tale (an example of ATU870) does not fall within the ATU Index entries for tales of magic, or fairy tales (300 to 749), but instead within the range of realistic tales (850 to 999). What is it, do you think, that makes this story like or unlike a fairy tale?

The ATU index (Aarne-Thompson-Uther index) is divided into seven sections (there’s that magical number again!):

1 to 299 Animal tales

300 to 749 Tales of magic (Fairy tales!)

750 to 849 Religious tales

850 to 999 Realistic tales (novelle)

1000 to 1199 Tales of the stupid ogre (or giant, or devil)

1200 to 1999 Anecdotes and jokes

2000 to 2399 Formula tales

Writing prompt

When Maid Maleen and her serving woman are walled up in the dark tower, they are provided with seven years of food and water, which signals the length of their prescribed sentence. It isn’t until the end of those seven years that the women finally attempt to escape (a feat they accomplish in just three days!) with the aid of a simple bread knife.

For this writing exercise, we will be exploring the concept of isolation and the passing of time, broken into two segments: reflection and renewal. To start off, set a timer for three minutes and write about a time when you experienced isolation. For example, you might write about a time of spiritual self-isolation, or a medically based period of isolation (such as a childhood experience with chicken pox or a dreaded teen encounter with the kissing disease), or even something as familiar and recent as a government-enforced quarantine due to a global pandemic. Write down everything that comes to mind. There is only one rule: don’t stop until the timer goes off!

Once you have completed your first task, reward yourself. Stretch your legs. Shake out your fingers. Pour yourself a drink. Do whatever you want as long as you step away from that fresh piece of writing. You need a few minutes to reset. When you return, scan your writing until you find a word or concept that grabs your attention. Think of this as your bread knife, the tool that will break you out of the darkness of the past. Sharpen those pencils and turn the page. Or open a new document. Set the timer for another three minutes and free-write with your chosen word or concept as your new launching point. When the buzzer rings STOP! And then, to honour the rule of threes, repeat the process one more time. Often, you will discover that you only need a little separation to change perspective from feeling stuck in the past to finding freedom in the moment.

References

Grimm, Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm 1884, Grimm’s Household Tales: Volume two, Margaret R Hunt (trans.), George Bell & Sons, London, viewed 14 April 2024, <https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Grimm%27s_Household_Tales,_Volume_2/Maid_Maleen>.

Heiner, Heidi Anne 2021, ‘Maid Maleen: Annotated Tale’, viewed 24 May 2024, <https://www.surlalunefairytales.com/h-r/maid-maleen/maid-maleen-tale.html>.

Langrish, K 2019, ‘“Maid Maleen”: A fairy-tale study of trauma’, Seven miles of steel thistles, blog post, 18 June, viewed 14 April 2024, <https://steelthistles.blogspot.com/2019/06/maid-maleen-fairytale-study-of-trauma.html>.

Jones, SS 1993 ‘The innocent persecuted heroine genre: An analysis of its structure and themes’, Western folklore, Vol. 52, No. 1, pp. 13-41.

Tatar, M 2003, The hard facts of the Brothers Grimm, Princeton University Press, Princeton.

Windling, T 2019, ‘The Folklore of Nettles’, Myth & moor, weblog, viewed 1 June 2024, <https://www.terriwindling.com/blog/2019/06/the-folklore-of-nettles.html>.

Zipes, J (trans) 2014, The original folk and fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm: the complete first edition, Princeton University Press, Princeton.

Zipes, J (ed, trans) 2001, The great fairy-tale tradition: from Straparola and Basile to the Brothers Grimm, WW Norton & Co, New York & London.

The name Maleen is believed to be the German short form of the name Magdalene, which means ‘woman from Magdala’, an ancient Jewish city with a name that translates as ‘tower’.

As a vertical structure linking heaven and earth, the tower can be seen as a symbolic ladder signalling ascent. When used as a prison, it becomes an in-between place, a symbol of stasis. According to Jack Zipes ‘The incarceration of a young woman in a tower (often to protect her chastity during puberty) was a common motif in various European myths and became part of the standard repertoire of medieval tales, lais, and romances throughout Europe, Africa, and the Orient’ (2001, p. 474).

The number seven carries mystical and sacred significance in philosophy, religion, and myth. It is considered a lucky number and believed to carry the sense of completeness.

Immurement or live entombment is a practice of imprisonment in which the victim is confined to an enclosed space. When provided with food and water, victims can survive for years after being walled up. Christian anchorites would voluntarily allow themselves to be immured, as part of their ascetic, spiritual practice.

Maleen accepts her father’s punishment and spends her sentence as directed. It isn’t until she realises that salvation might not be forthcoming that she attempts to escape. According to Steven Swann Jones this marks the end of the first act of this tale type.

The number three is considered a perfect number and is referenced widely in fairy tales and folklore. The movement from stasis (death) and entombment to liberation (life) also has parallels to the Biblical resurrection of Jesus Christ (Matthew 12:40).

Known by the scientific name Urtica dioica, this herbaceous plant has jagged leaves and stinging hairs. Historically, it has been used as a source of food, traditional medicine, and fibre arts. According to Terri Windling ‘nettles have long been associated with women’s domestic magic: with inner strength and fortitude, with healing and also self-healing, with protection and also self-protection’ (2019).

According to Steven Swann Jones, this signals the move to the second act in the narrative cycle of the Innocent Persecuted Heroine. Now that Maid Maleen has escaped, she is taken into service in the court of the same prince whose forbidden love caused Maid Maleen's imprisonment in the tower. Maria Tatar writes that fairy-tale heroines who escape oppression ‘often undertake a journey that succeeds only in landing them at the site of new forms of domestic drudgery’ (2003, p. 116).

Note that this is the last mention of Maid Maleen’s companion during her imprisonment: after this moment, the two women of the tale are Maleen and the false bride.

In other versions of this tale type, the false bride is a witch, and/or is already pregnant.

Nettles must be blanched to remove the sting before being eaten. The fact that Maid Maleen ate them raw adds to the suffering she endured during her travels.

In this version of the tale, the true bride/Maid Maleen speaks to a nettle plant, a footbridge, and the church door. In other versions, the first thing she speaks to is her horse (then a bridge, then the church door).

A bridge symbolises communication and union. Crossing over a bridge represents a transition, or crossing, from one state to another.

A door is another symbol of a threshold or place of transition; it is a boundary between one state of being and another.

In other versions of this tale the false bride gives her various objects (a glove, muffler, necklace, ring, and belt), all of which she loses on the way back to the palace, and all of which the prince/groom collects after the drops them.

In other versions of this tale type, the prince asks for the various items the true bride dropped or lost after they left the church (the glove, muffler, necklace, ring, and belt). Usually the prince asks after three items (rather than just the one, as in this version).

In Tale Type 870C, the true bride is revealed not because she is wearing the jewels the prince gave her, but by ‘a stone indicating chastity’, which is motif H411.1 in the Stith Thompson Index.

This rhyme is from the oral folklore tradition; the first known recording of the song is from Waldimir Labeller’s Kling-Klang Gloria: German Volks and Kinderlieder, a collection of forty-six German lyric poems and folk songs, which was first published in 1907.

Maid Maleen in the Dark Tower

Seven years in the cold tower,

with only the blade of women's talk

to cut the quiet.

Seven years of food

getting ever more stale,

harder to cut,

more difficult to portion.

Seven years away from the world,

but even through stone walls

we can sense change,

as faint sounds move from wooden wheels

to those encased in iron.

Seven years to sharpen a knife

slick enough to scrape out mortar.

Seven stones removed to let in the sunlight.

This is how long it took me

to cut through red tape,

and receive labels

that shed light on who I am.

*****

I found it intriguing that escaping the tower was only the beginning of the story. Surviving hunger and poverty, and then finding the strength to reclaim herself as the true bride seemed the more difficult task for Maid Maleen. I'm not sure how often the exploration of psychological trauma appears in fairy tales. For me, it added depth and realism to the story. Also, the information in the footnotes was extremely interesting--thank you for including them.