The Grimm brothers' 'Rumpelstiltskin'

A traditional tale, with a brief introduction, discussion questions, and a writing prompt

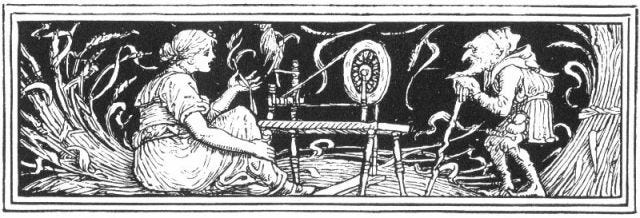

Once upon a time, a miller boasted that his daughter was the finest spinner in the world, so magnificent in fact that she could spin straw into gold. The greedy king of the land hears the boast and spirits the girl away to his castle. He locks her in a chamber filled with straw and orders her to turn it into gold under the penalty of death. That night an ugly little man appears with the offer to perform the impossible task. She offers her necklace in exchange. On the second night, the king places her in a larger chamber with the same demands. This time the little man claims the ring on the girl’s finger. On the third night, the king puts the maiden in the largest chamber yet, only this time he promises that if she can transform the mountain of straw into gold, she will become his queen. However, the miller’s daughter has nothing left to trade, so she is forced to promise the dwarf her first-born child.

In this issue of The Orange & Bee, we are exploring ‘Rumpelstiltskin,’ which Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm originally published as ‘Rumpelstiltzkin’ in Kinder- und hausmärchen (Children's and household tales) in 1812. Although the Grimms’ story is the best known version of this tale, there are several other variants in existence, most of which are European in origin. The Grimms’ tale actually draws from three different oral variants ‘in which the girl’s predicament lies in her inability to spin anything but gold’ (Zipes 2000, p. 429). In this case, the protagonist needs help to fulfill the domestic task in order to win a bid for marriage. Grimms’ ‘Rumpelstiltzkin’ twists this with the dwarf spinning straw into gold. They also included the name-guessing motif, which can be found in numerous legends such the Norwegian story of ‘King Olaf and the Giant’, which Jacob Grimm related in his 1835 treatise Deutsche Mythologie (Teutonic Mythology).

Introduction to the Brothers Grimm Rumpelstilzchen (Rumpelstiltskin)

‘Rumpelstiltskin’ is an example of tale type ATU 500, The name of the supernatural helper, which falls within the range of supernatural helpers tales (500 to 559) within the Aarne-Thompson-Uther Index (ATU Index).

Examples of ATU500 tale type include:

‘Tom Tit Tot’ collected by Joseph Jacobs in English Fairy Tales (London: David Nutt, 1898).

‘The girl who could spin gold from clay and long straw’ collected by Benjamin Thorpe in Yule-Tide Stories: A Collection of Scandinavian and North German Popular Tales and Traditions, from the Swedish, Danish, and German (London: Henry G. Bohn, 1853).

‘Duffy and the devil’ collected by Robert Hunt in Popular Romances of the West of England; or, The Drolls, Traditions, and Superstitions of Old Cornwall (London: John Camden Hotten, 1871).

‘Whuppity Stoorie’ collected by John Rhys in Celtic Folklore: Welsh and Manx (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1901).

A study published by Royal Society Open Science claims that although stories classified as ATU 500 ‘The name of the supernatural helper’ (‘Rumplestiltskin’) were first written down in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, this tale type can be ‘traced back to the emergence of the major western Indo-European subfamilies as distinct lineages between 2500 and 6000 years ago’ (Silva and Tehrani, 2016).

Rumpelstiltskin: story and annotations

‘Rumpelstiltskin’ was translated by Edgar Taylor for an English edition of Jacob and Wilhelm Grimms’ Household tales first published in 1823. You can find a digitised version of this translation at Project Gutenberg. A simplified version of this tale was collected by Andrew Lang in The blue fairy book first published in 1889. For those of you looking for a print version, we suggest that you check out The original folk and fairy tales of the Brothers Grimm: The complete first edition (2014), edited and translated by Jack Zipes.

By the side of a wood, in a country a long way off, ran a fine stream of water; and upon the stream there stood a mill. The miller’s house was close by, and the miller1, you must know, had a very beautiful daughter. She was, moreover, very shrewd and clever; and the miller was so proud of her, that he one day told the king of the land, who used to come and hunt in the wood, that his daughter could spin gold2 out of straw.

Now this king was very fond of money. When he heard the miller’s boast, the king’s greediness was raised, and he sent for the girl to be brought before him. Then he led her to a chamber in his palace where there was a great heap of straw, and gave her a spinning wheel3, and said, ‘All this must be spun into gold before morning, as you love your life.’

It was in vain that the poor maiden said that it was only a silly boast of her father, for that she could do no such thing as spin straw into gold: the chamber door was locked, and she was left alone.

She sat down in one corner of the room, and began to bewail her hard fate; when on a sudden the door opened, and a droll-looking little man hobbled in, and said, ‘Good morrow to you, my good lass; what are you weeping for?’

‘Alas!’ said she, ‘I must spin this straw into gold, and I know not how.’4

‘What will you give me,’ said the hobgoblin5, ‘to do it for you?’

‘My necklace6,’ replied the maiden.

He took her at her word, and sat himself down to the wheel, and whistled and sang:

‘Round about, round about, Lo and behold! Reel away, reel away, Straw into gold!’

And round about the wheel went merrily; the work was quickly done, and the straw was all spun into gold.

When the king came and saw this, he was greatly astonished and pleased; but his heart grew still more greedy of gain, and he shut up the poor miller’s daughter again with a fresh task.

Then she knew not what to do, and sat down once more to weep; but the dwarf7 soon opened the door, and said, ‘What will you give me to do your task?’

‘The ring8 on my finger,’ said she.

So her little friend took the ring, and began to work at the wheel again, and whistled and sang:

‘Round about, round about, Lo and behold! Reel away, reel away, Straw into gold!’

till, long before morning, all was done again.

The king was greatly delighted to see all this glittering treasure; but still he had not enough: so he took the miller’s daughter to a yet larger heap, and said, ‘All this must be spun tonight9; and if it is, you shall be my queen.’

As soon as she was alone that dwarf came in, and said, ‘What will you give me to spin gold for you this third time?’

‘I have nothing left,’ said she.

‘Then say you will give me,’ said the little man, ‘the first little child10 that you may have when you are queen.’

‘That may never be,’ thought the miller’s daughter: and as she knew no other way to get her task done, she said she would do what he asked.

Round went the wheel again to the old song, and the manikin11 once more spun the heap into gold. The king came in the morning, and, finding all he wanted, was forced to keep his word; so he married the miller’s daughter, and she really became queen.

At the birth of her first little child she was very glad, and forgot the dwarf, and what she had said. But one day he came into her room, where she was sitting playing with her baby, and put her in mind of it. Then she grieved sorely at her misfortune, and said she would give him all the wealth of the kingdom if he would let her off, but in vain; till at last her tears softened him, and he said, ‘I will give you three12 days’ grace, and if during that time you tell me my name13, you shall keep your child.’

Now the queen lay awake all night, thinking of all the odd names that she had ever heard; and she sent messengers all over the land to find out new ones. The next day the little man came, and she began with TIMOTHY, ICHABOD, BENJAMIN, JEREMIAH, and all the names she could remember; but to all and each of them he said, ‘Madam, that is not my name.’

The second day she began with all the comical names she could hear of, BANDY-LEGS, HUNCHBACK, CROOK-SHANKS, and so on; but the little gentleman still said to every one of them, ‘Madam, that is not my name.’

The third day one of the messengers came back, and said, ‘I have travelled two days without hearing of any other names; but yesterday, as I was climbing a high hill, among the trees of the forest where the fox and the hare bid each other good night, I saw a little hut; and before the hut burnt a fire; and round about the fire a funny little dwarf was dancing upon one leg, and singing:

‘Merrily the feast I’ll make. Today I’ll brew, tomorrow bake; Merrily I’ll dance and sing, For next day will a stranger bring. Little does my lady dream Rumpelstiltskin is my name!’

When the queen heard this she jumped for joy, and as soon as her little friend came she sat down upon her throne, and called all her court round to enjoy the fun; and the nurse stood by her side with the baby in her arms, as if it was quite ready to be given up. Then the little man began to chuckle at the thought of having the poor child, to take home with him to his hut in the woods; and he cried out, ‘Now, lady, what is my name14?’

‘Is it JOHN?’ asked she.

‘No, madam!’

‘Is it TOM?’

‘No, madam!’

‘Is it JEMMY?’

‘It is not.’

‘Can your name be RUMPELSTILTSKIN15?’ said the lady slyly.

‘Some witch told you that!—some witch told you that!’ cried the little man, and dashed his right foot in a rage so deep into the floor, that he was forced to lay hold of it with both hands to pull it out.

Then he made the best of his way off, while the nurse laughed and the baby crowed; and all the court jeered at him for having had so much trouble for nothing, and said, ‘We wish you a very good morning, and a merry feast, Mr RUMPLESTILTSKIN!’

Discussion questions

Rumpelstiltskin belongs to the ATU tale type 500: the name of the helper. And it’s as varied as you might expect. In addition to Rumpelstiltskin, other names found categorized under this tale type include Batzibitzili, Doppeltürk, Holzrührlein Bonneführlein, Nägendümer, Panzimanzi, Purzinigele, Tarandandò, Titeliture, Whuppity Stoorie, Winterkölbl, Zirkzirk ... and the list goes on. ‘Whether he makes an appearance as Ricdin-Ricdin in a French tale or as Tom Tit Tom in an English tale, his essence and function remain much the same’ (Tatar 124). The binding power of naming plays a central part of the plot in these tales, hence the name of the tale type. (For those of you interested in doing a deep dive on names, we highly recommend reading ‘Naming and identity in myths, legends, fairy tales & fantasy’ by Katherine Langrish posted at her delightful blog Seven miles of steel thistles.) Consider some of your favorite (and despised) fairy tales characters. What are your thoughts about the power of names? What do names suggest about the degree of freedom and agency characters experience within their stories?

In Disability, deformity, and disease in the Grimms’ fairy tales, Ann Schmiesing notes that ‘disability and deformity are of course markers not only of the outcast underdog but also of wicked characters’ (140). This is evident in the descriptions of Rumpelstiltskin as a little man, a hobgoblin, a dwarf, and a manikin. On the second day of guessing, the queen turns to ‘comical’ names, all of which indicate physical disabilities: BANDY-LEGS, HUNCHBACK, and CROOK-SHANKS, which ‘suggests a fear that he is an agent of disease who will deform or kill her child’ (Schmiesing 142). How does the meaning of this story shift when viewing ‘Rumpelstiltskin’ through an ableist lens? How does the narrative construct difference as disability?

Writing prompt

In the thought-provoking essay ‘ The problem with justice’—included in the new book Just wonder: shifting perspectives in tradition, edited by Pauline Greenhill and Jennifer Orme—Veronica Schanoes explores the concept of justice in fairy tales. She poses the question of what justice might ‘look like for Jews in the European fairy-tale tradition’ (Schanoes 2024, 61), something she explores in her ‘Rumpelstiltskin’ retelling ‘Burning Girls’.

‘With respect to feminist rewritings of fairy tales … revision not only reemphasizes the earlier tale from which it is born, it actually depends on it to develop meaning. Perhaps keeping the older stories in consciousness is part of the process of justice’, writes Schanoes (62-63). ‘It is long past time we look unflinchingly at the ways fairy tales and folktales affect and are inflected by discourses of race, religion, and sovereignty, the roles they plat in constructing mainstream representations of marginalized communities’ (65).

What other fairy tales can you identify that could use a recasting of justice? Dig deeper, lean into the meaning of the original tale, and then rewrite the selection with with a mindful and inclusive approach geared towards the world we live in today.

References

Ashliman, D. L. 2022, ‘The name of the helper: Folktales of type 500, and related tales,

in which a mysterious and threatening helper is defeated when the hero or heroine discovers his name’, University of Pittsburgh, viewed 22 May 2025, <https://sites.pitt.edu/~dash/type0500.html>.

Briggs, K 1976, An encyclopedia of fairies: hobgoblins, brownies, bogies, and other supernatural creatures, Pantheon Books, New York.

Cloud, E 1898, Tom Tit Tot; an essay on savage philosophy in folk-tale, Duckworth and co., London.

Cooper, J. C. 1987, An illustrated encyclopedia of traditional symbols, Thames & Hudson, New York.

Cunningham, M 2015, ‘Little man’, The New Yorker, viewed 22 May 2025, <https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2015/08/10/little-man>.

Graça da Silva, S and Tehrani, JJ 2016 ‘Comparative phylogenetic analyses uncover the ancient roots of Indo-European folktales, Royal Society Open Science, Vol. 20, No. 3, viewed 15 May 2025, < https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.150645>.

Grimm, J and W1823, Grimm’s household tales, Edgar Taylor (trans.), C. Baldwyn, London, viewed 15 May 2025, <https://www.gutenberg.org/files/2591/2591-h/2591-h.htm#link2H_4_0027>.

Heiner, H A 2021, ‘Rumpelstiltskin: annotated tale’, viewed 15 May 2025, <https://surlalunefairytales.com/h-r/rumplestiltskin/rumplestiltskin-tale.html>.

Langrish, K 2023, ‘Naming and identity in myths, legends, fairy tales & fantasy’, Seven miles of steel thistles, viewed 23 May 2025, <https://steelthistles.blogspot.com/2023/04/naming-and-identity-in-myths-legends.html>.

Room, A (rev.) 1995, Brewer’s dictionary of phrase and fable: 15th edition, Harper Collins, New York.

Schanoes, V 2021, ‘Burning girls’, Burning girls and other stories, A Tom Doherty Associates Book, New York.

Schanoes, V 2024, ‘The problem with justice’, Just wonder: shifting perspectives in tradition, Greenhill, P and Orme, J (eds.), Utah Sate University Press, Logan.

Schmiesing, A 4014, Disability, deformity, and disease in the Grimms’ fairy tales, Wayne State University Press, Detroit.

Tatar, M 1987, The hard facts of the Brothers Grimm, Princeton University Press, Princeton.

Zipes, J (trans) 2014, The original folk and fairy tales of the Brothers Grimm: the complete first edition, Princeton University Press, Princeton.

A miller is a person who operates a mill with the specific task of grinding grain into flour (Merriam-Webster).

Alchemists believed that gold represented the sun, illumination, and wisdom. It was believed to be the equilibrium of all metallic properties (Cooper 74). Maria Tatar notes that the underlying premise of ‘Rumpelstiltskin’ rests on the idea that ‘a daughter who produces wealth, whether through her own labor or through magical means, is a girl who can make a good marriage’ (126).

A spinning wheel is ‘a small domestic hand-driven or foot-driven machine for spinning yarn or thread’ (Merriam-Webster). Spinning is one of the domestic arts. Spinning represents the feminine principle (Cooper 156). Maria Tatar finds irony in the tale: The daughter ‘works her way up the ladder of social success through her alleged accomplishments as a spinner, yet also manages to avoid sitting down at the spinning wheel’ (Tatar 123).

Maria Tatar notes that in a random sampling of seventeen ‘Rumpelstiltskin’ variants, ‘eleven turn on the issue of spinning vast quantities of flax in a ludicrously brief span of time; six are concerned with transforming straw or flax into gold’ (Tatar 124).

Although Puritans defined hobgoblins as malevolent spirits, Katherine Briggs points to earlier sources that reveal hobgoblins as friendly but tricksy fairies. ‘They are, on the whole, good-humoured and ready to be helpful, but fond of practical joking, and like most of the FAIRIES rather nasty people to annoy’ (Briggs 223).

A necklace represents dignity (Cooper 111).

Dwarfs are guardians of mineral wealth. They are often depicted as stunted and grotesque. And though not unfriendly, they could become vindictive or mischievous (Brewer’s 339).

A ring represents power dignity, and strength. ‘To bestow a ring is to transfer power (Cooper 138).

The fact that the little man completes these tasks at night aligns with concept of the esoteric nature of initiation and illumination (Cooper 112).

Several writers have explored the theme of Rumpelstiltskin’s desire for a child, including ‘Little man’ by Michael Cunningham. Likewise, Maria Tatar traces the evolution of the agreement between Rumpelstiltskin and the miller’s daughter: ‘Above all, a child—a product of the queen’s labor—comes to be exchanged for something that is its equivalent, if only in lexical terms: the product of the demon’s labors. These labors become more closely affiliated with spinning, turning “Rumpelstiltskin” into a story that thematicizes the very labor that gave birth to it (132).

The word manikin comes from the Dutch mannekijn, which means ‘little man’.

Three is a common number used in fairy tales. Rumpelstiltskin comes to the aid of the miller’s daughter three times. Here, he gives her three days to guess his name. The number three symbolizes creative power, growth, and synthesis (Cooper 114).

Jack Zipes notes that the name-guessing motif in ‘Rumpelstiltskin’ links the tale to Giacomo Puccini’s opera Turandot (429).

This is a reference to Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, II, ii (1594); ‘What’s in a name? That which we call a rose/ By any other name would smell as sweet.’

According to the Brewer’s dictionary of phrase and fable, the name Rumpelstiltskin ‘literally means “wrinkled foreskin”’ (935).

"Wrinkled foreskin" hahahaha, OMG the interpretations!

Favorite story my mom read to me when I was a child.