Charles Perrault's La Barbe bleüe (Bluebeard)

A traditional tale, with a brief introduction, discussion questions, and a writing prompt

For the last issue of our first year, we are taking a look at ‘La Barbe bleüe’ (Bluebeard) as our featured fairy tale. Taken from the French folk tradition, Charles Perrault first published this story in his collection of literary fairy tales, Histoires ou contes du temps passé, avec des moralités (Stories or tales of past times), in 1697. Although ‘Bluebeard’ ends on a happy note, it takes a sharp turn in the middle when the protagonist of the tale realizes she married a murderer. As noted by Bruno Bettelheim, Perrault’s tale offers a flip side to ‘Beauty and the Beast’, a morality tale meant to prepare young women entering arranged marriages. For in ‘Bluebeard’, the protagonist willingly weds a wealthy man despite her aversion to his frightful appearance. The heroine is forbidden one thing only: entrance to his private domain, a secret room filled with the dead bodies of long line of disobedient wives. In this tale, marriage is portrayed as dangerous and potentially life-threatening, one of the reasons Bluebeard continues to inspire contemporary writers seeking to explore issues related to domestic violence.

Introduction to Charles Perrault’s La Barbe bleüe (Bluebeard)

‘Bluebeard’ is an example of tale type ATU312, which is dedicated to the tale sometimes referred to as the maiden-killer. There are several variants of ATU312, which falls under the range of tales with supernatural adversaries (ATU 300-399) including ATU312a The brother rescues his sister from the tiger, 312b Two sisters carried off by a diabolic being, 312c Devil’s bride rescued by a brother, and 312d Brother saves his sister and brothers from the dragon. Similar tales include those classified as ATU311 including ‘Fitcher's bird’ and ‘How the devil married three sisters’.

‘Barbe-Bleue: Légende d'Auvergne’ (Bluebeard: a legend from Auvergne) collected by Antoinette Bon in Revue des traditions populaires, vol. 2 (Paris 1898).

‘The white dove’ collected by Gaston Maugard in Contes des Pyrénées. An English translation of the Maugard’s ‘The white dove’ was also included in Andrew Lang’s The pink fairy book (1897).

‘Don Firriulieddu’ collected by Thomas Frederick Crane in Italian Popular Tales (London: Macmillan and Company 1885).

‘Asphurtzela’ collected and translated by Marjory Wardrop in Georgian Folk Tales (London: David Nutt 1894).

‘Childe Rowland’ (ATU312D) collected by Joseph Jacobs in English Fairy Tales (1890).

‘The Brahman girl that married a tiger’ collected by Mrs Howard Kingscote and Pandit Natêsá Sástrî in Tales of the sun; or, folklore of southern India (London: W. H. Allen and Company 1890).

La Barbe bleüe (Bluebeard): story and annotations

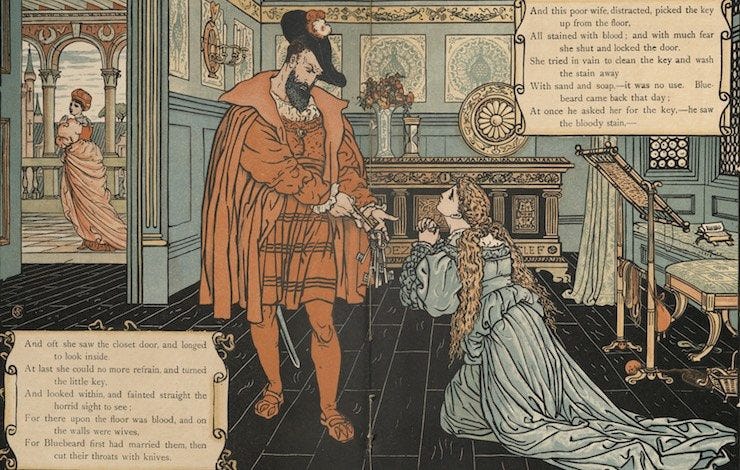

‘La Barbe bleüe’ (Bluebeard) made its literary debut in 1697 with the publication of Charles Perrault’s collection of fairy tales in Histoires ou contes du temps passé, avec des moralités (Stories or tales of past times). The man with the bold blue beard marries a young woman and removes her from the safety of her childhood home to his opulent (and remote) estate. Before long, he leaves his new bride with a set of keys that will open every room in his mansion. He encourages her to enjoy the wealth displayed behind each door. The only restriction is the room behind a small door at the end of a long hall on the ground floor. This room is reserved for him. After all, shouldn’t every man have his private pleasures? However instead of taking the key to that forbidden chamber, he leaves it on the ring in her safekeeping.

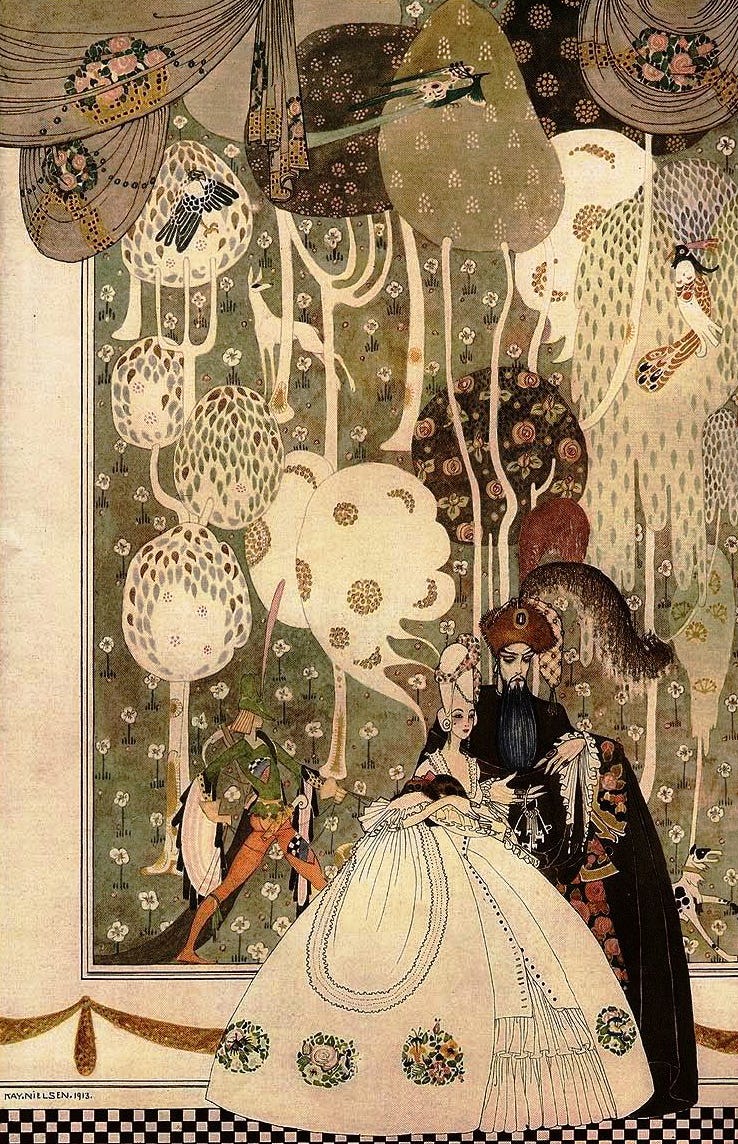

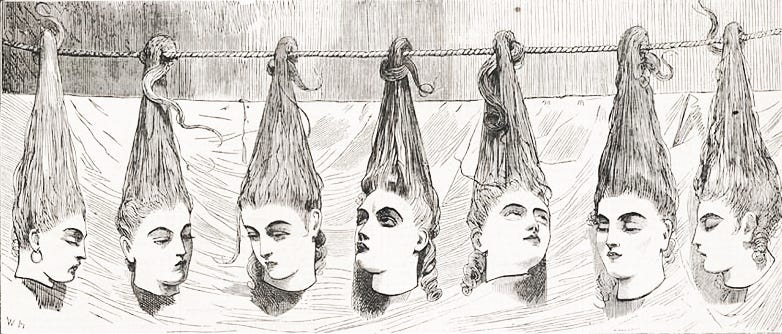

He leaves. She opens the door. And quickly discovers some secrets are better left undisturbed. For her aristocratic husband is revealed as a mass murderer, his dead wives hanging from the walls, their blood clotted on the floor. The living bride drops the key, which magically absorbs the blood—a tell-tale stain that cannot be removed by any means. Bluebeard returns home and demands the key and the damning evidence of her disobedience. The price for her transgression is execution. However, she is saved at the last moment when her brothers arrive and cut down the killer with their sharp swords.

Other French tales featuring murderous bridegrooms include ‘Fitcher’s Bird’(ATU311: the heroine rescues herself and her sisters) and the ‘Robber Bridegroom’ (ATU955: the robber bridegroom), both of which were recorded by Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm (Zipes 56). The Grimm Brothers also included ‘Blaubart’ (Bluebeard) in the first edition of Kinder- und Hausmärchen (Children’s and household tales), but they removed it from later versions ‘due to its obviously close relationship to Perrault's tale’ (Heiner, SurLaLune fairy tales).

‘Bluebeard’ was translated from French and collected in Andrew Lang’s The blue fairy book (1889).

An English version of ‘Bluebeard', famously illustrated by Harry Clarke and introduced by Thomas Bodkin, is included in The Fairy Tales of Charles Perrault (1922).

Angela Carter translated ‘Bluebeard’ in The fairy tales of Charles Perrault (Victor Gollancz 1977). These translations were rereleased with an introduction by Jack Zipes in Angela Carter: Little Red Riding Hood, Cinderella, and other classic tales of Charles Perrault (Penguin Books 2008).

Translating is not a mechanical art. Perrault inspired Carter to delve more deeply into the origins and meanings of fairy tales, but she had to misread him or reinterpret him to make his tales more palatable to her feminist and political sensitivity. Clearly she sensed the problematic aspects of Perrault’s style and ideology, which she purposely glossed over in her translation, and this may have made her so dissatisfied that she was ‘driven’ to revisit Perrault’s tales in a dramatically and radically different way in The Bloody Chamber, while she was translating Perrault’s tales (Zipes 2008).

There was a man who had fine houses, both in town and country, a deal of silver and gold plate, embroidered furniture, and coaches gilded all over with gold. But this man was so unlucky as to have a blue beard1, which made him so frightfully ugly that all the women and girls ran away from him.

One of his neighbors, a lady of quality, had two daughters who were perfect beauties. He desired one of them in marriage, leaving her to choose which of the two she would bestow on him. They would neither of them have him and sent him backward and forward from one another, not being able to bear the thoughts of marrying a man who had a blue2 beard3, and what besides gave them disgust and aversion was his having already been married to several wives4, and nobody ever knew what became of them.

Bluebeard, to engage their affection, took them, with the lady their mother and three or four ladies of their acquaintance, along with other young people of the neighborhood, to one of his country seats5, where they stayed a whole week.

There was nothing then to be seen but parties of pleasure, hunting, fishing, dancing, mirth, and feasting. Nobody went to bed but all passed the night in rallying and joking with each other. In short, everything succeeded so well that the youngest daughter began to think the master of the house not to have a beard so very blue, and that he was a mighty civil gentleman.

As soon as they returned home, the marriage was concluded. About a month afterward, Bluebeard told his wife that he was obliged to take a country journey for six weeks at least, about affairs of very great consequence, desiring her to divert herself in his absence, to send for her friends and acquaintances, to carry them into the country, if she pleased, and to make good cheer wherever she was.

‘Here,’ he said, ‘are the keys6 of the two great wardrobes, wherein I have my best furniture; these are of my silver and gold plate, which is not every day in use; these open my strong boxes, which hold my money, both gold and silver; these my caskets of jewels; and this is the master-key to all my apartments. But for this little one here, it is the key of the closet at the end of the great gallery on the ground floor. Open them all; go into all and every one of them, except that little closet, which I forbid you, and forbid it in such a manner that, if you happen to open it, there’s nothing but what you may expect from my just anger and resentment.’

She promised to observe, very exactly, whatever he had ordered; when he, after having embraced her, got into his coach and proceeded on his journey.

Her neighbours and good friends did not stay to be sent for by the new married lady, so great was their impatience to see all the rich furniture of her house, not daring to come while her husband was there, because of his blue beard, which frightened them. They ran through all the rooms, closets, and wardrobes, which were all so fine and rich that they seemed to surpass one another.

After that they went up into the two great rooms, where was the best and richest furniture; they could not sufficiently admire the number and beauty of the tapestry, beds, couches, cabinets, stands, tables, and looking-glasses, in which you might see yourself from head to foot; some of them were framed with glass, others with silver, plain and gilded, the finest and most magnificent ever were seen.

They ceased not to extol and envy the happiness of their friend, who in the meantime in no way diverted herself in looking upon all these rich things, because of the impatience she had to go and open the closet on the ground floor. She was so much pressed by her curiosity7 that, without considering that it was very uncivil to leave her company, she went down a little back staircase, and with such excessive haste that she had twice or thrice like to have broken her neck.

Coming to the closet-door, she made a stop for some time, thinking upon her husband’s orders, and considering what unhappiness might attend her if she was disobedient; but the temptation was so strong she could not overcome it. She then took the little key, and opened it, trembling, but could not at first see anything plainly, because the windows were shut. After some moments she began to perceive that the floor was all covered over with clotted blood, on which lay the bodies of several dead women, ranged against the walls. (These were all the wives whom Bluebeard had married and murdered, one after another.) She thought she should have died for fear, and the key, which she pulled out of the lock, fell out of her hand.

After having somewhat recovered her surprise, she took up the key, locked the door, and went upstairs into her chamber to recover herself; but she could not, she was so much frightened. Having observed that the key of the closet was stained with blood8, she tried two or three times to wipe it off, but the blood would not come out; in vain did she wash it, and even rub it with soap and sand; the blood still remained, for the key was magical and she could never make it quite clean; when the blood was gone off from one side, it came again on the other.

Bluebeard returned from his journey the same evening, and said he had received letters upon the road, informing him that the affair he went about was ended to his advantage. His wife did all she could to convince him she was extremely glad of his speedy return.

Next morning he asked her for the keys, which she gave him, but with such a trembling hand that he easily guessed what had happened.

‘What!’ said he, ‘is not the key of my closet among the rest?’

‘I must certainly have left it above upon the table,’ said she.

‘Fail not to bring it to me presently,’ said Bluebeard.

After several goings backward and forward she was forced to bring him the key. Bluebeard, having very attentively considered it, said to his wife,

‘How comes this blood9 upon the key?’

‘I do not know,’ cried the poor woman, paler than death.

‘You do not know!’ replied Bluebeard. ‘I very well know. You were resolved to go into the closet, were you not? Mighty well, madam; you shall go in, and take your place among the ladies you saw there.’

Upon this she threw herself at her husband’s feet and begged his pardon with all the signs of true repentance, vowing that she would never more be disobedient. She would have melted a rock, so beautiful and sorrowful was she; but Bluebeard had a heart harder than any rock!

‘You must die, madam,’ said he, ‘and that presently.’

‘Since I must die,’ answered she (looking upon him with her eyes all bathed in tears), ‘give me some little time to say my prayers.’

‘I give you,’ replied Bluebeard, ‘half a quarter of an hour, but not one moment more.’

When she was alone, she called out to her sister, and said to her: ‘Sister Anne,’10 (for that was her name), ‘go up, I beg you, upon the top of the tower, and look if my brothers are not coming over; they promised me that they would come to-day, and if you see them, give them a sign to make haste.’

Her sister Anne went up upon the top of the tower, and the poor afflicted wife cried out from time to time:

‘Anne, sister Anne, do you see anyone coming?’

And sister Anne said: ‘I see nothing but the sun, which makes a dust, and the grass, which looks green.’

In the meanwhile, Bluebeard, holding a great sabre11 in his hand, cried out as loud as he could bawl to his wife: ‘Come down instantly, or I shall come up to you.’

‘One moment longer, if you please,’ said his wife, and then she cried out very softly, ‘Anne, sister Anne, dost thou see anybody coming?’

And sister Anne answered: ‘I see nothing but the sun, which makes a dust, and the grass, which is green.’

‘Come down quickly,’ cried Bluebeard, ‘or I will come up to you.’

‘I am coming,’ answered his wife; and then she cried, ‘Anne, sister Anne, dost thou not see anyone coming?’

“I see,” replied sister Anne, “a great dust, which comes on this side here.”

‘Are they my brothers?’

‘Alas! no, my dear sister, I see a flock of sheep.’

‘Will you not come down?’ cried Bluebeard

‘One moment longer,’ said his wife, and then she cried out: ‘Anne, sister Anne, dost thou see nobody coming?’

‘I see,’ said she, ‘two horsemen, but they are yet a great way off.’

‘God be praised,’ replied the poor wife joyfully; ‘they are my brothers; I will make them a sign, as well as I can, for them to make haste.’

Then Bluebeard bawled out so loud that he made the whole house tremble. The distressed wife came down, and threw herself at his feet, all in tears, with her hair about her shoulders.

‘This signifies nothing,’ says Bluebeard; ‘you must die’; then, taking hold of her hair with one hand and lifting up the sword with the other, he was going to take off her head. The poor lady, turning about to him, and looking at him with dying eyes, desired him to afford her one little moment to recollect herself.

‘No, no,’ said he, ‘recommend thyself to God,’ and was just ready to strike...

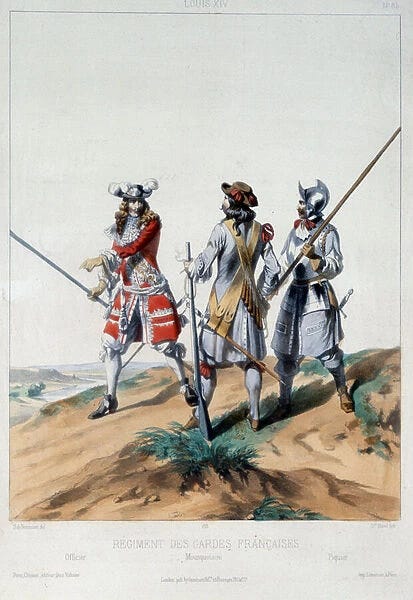

At this very instant there was such a loud knocking at the gate that Bluebeard made a sudden stop. The gate was opened, and presently entered two horsemen, who, drawing their swords, ran directly to Bluebeard. He knew them to be his wife’s brothers, one a dragoon12, the other a musketeer13, so that he ran away immediately to save himself; but the two brothers pursued so close that they overtook him before he could get to the steps of the porch, when they ran their swords through his body and left him dead. The poor wife was almost as dead as her husband and had not strength enough to rise and welcome her brothers.

Bluebeard had no heirs, and so his wife became mistress of all his estate. She made use of one part of it to marry her sister Anne to a young gentleman who had loved her a long while; another part to buy captains commissions for her brothers, and the rest to marry herself to a very worthy gentleman, who made her forget the ill time she had passed with Bluebeard.

Moral

Curiosity, in spite of its appeal,

May often cost a horrendous deal.

A thousand new cases arise each day,

With due respect, oh ladies, the thrill is slight:

As soon as you quench it, it goes away.

In truth, the price one pays is never right.14

Another Moral

Provided one has common sense

And learned to grasp complex texts,

This story bears evidence

Of taking place in the past tense.

No longer are husbands terrible to see,

No longer do they demand the untarnished key.

Though he may be jealous and dissatisfied,

A husband tried to do as he’s obliged.

And whatever colour his beard may be,

It’s difficult to know who the master may be.

Discussion prompt

Zipes reminds readers that the reading of the bloody key as a marker of disobedience and infidelity is ‘wilfully wrong-headed in its effort to vilify Bluebeard’s wife’ (56). Perrault’s tongue-in-cheek commentary on the evils of female curiosity is so prevalent, later editions and illustrated tellings were often labelled with a subtitle, ‘the effects of female curiosity’ or ‘the fatal effects of curiosity’. As such, ‘Bluebeard’ falls ‘in line with cautionary tales about women’s innate wickedness: with Pandora who opened the forbidden casket as well as Eve who ate the forbidden fruit’ (Warner 244). Although the story never justifies Bluebeard’s violence, the ‘cardinal sin’ of the heroine’s curiosity is inflated, as is the consequence (death by execution), compare to the simple misstep: ‘the bloodbath is simply too sensational a spectacle for so minor a transgression’ (Tater 164).

Nevertheless, though it’s often read as a story warning women not to be curious or disobedient, the story is clearly one in which the foreigner husband/murderer is the monstrous Other, and the courageous and curious bride the sympathetic (and surviving) heroine. In this sense, the story can as easily be read as a critique of gender-based control and violence.

Is it, do you think, a feminist fairy tale, or a celebration of outdated ideas about women’s curiosity? Or a little of both?

In a recent interview with The Rumpus, Kelly Link comments on the use of satire in representing the upper class:

What I do know is that fairy tales are a populist form—they grant power and wealth to deserving characters, sometimes, and they punish characters who are greedy, or who behave poorly. The happy ending of a fairy tale just as often reasserts the typical order, with a new king instead of looking toward a world in which there are no kings. Is the fairytale regressive or is it revolutionary or is it both?

Writing prompt

In Issue one, we featured Jeana Jorgensen’s poem ‘Bluebeard’. This is an example of a concrete poem, which uses an arrangement of words, letters, colors, and typefaces to create a graphic representation of a physical object. In Jorgensen’s case, she used the shape of an ornate key to create added connections to her text. How might the narrative change depending on the type of key/s being depicted? For those of you interested in putting a poetic spin on ‘Bluebeard’, you might want to try your hand at a found poem, which is a type of literary collage. Take words and phrases from Perrault’s tale and/or other versions such as Angela Carter’s ‘The bloody chamber’. You can also draw from additional texts such as medical journals, historical accounts, and newspaper articles. Splice and paste, change it up with white space and line breaks, add and subtract words and images. Do whatever you want, but make sure to keep a sense of play in the foreground as you transform the old into something new.

Most intellectual development depends upon new readings of old texts. I am all for putting new wine in old bottles, especially if the pressure of the new wine makes the bottles explode. (Angela Carter, ‘Notes from the Front Line’, On Gender and Writing, 1983, p. 69)

For a different take on this story, pick a different perspective. (Dorian Wolfe takes this approach in ‘The letter K’, a fabulous piece of flash fiction featured in Issue three of The Orange & Bee.) How might ‘Bluebeard’ look if it was told from the husband’s point of view? Another option might be Anne (the only other named character in the story). How does she view the situation? If you want to push the tale type even further, try telling the story from the point of view of someone unexpected. For instance, what happened to Bluebeard’s first wife? (Catherynne M. Valente took this approach in a Bluebeard/Garden of Eden mashup featured in the novella Comfort Me With Apples.) What other characters can you interview? What about the housekeeper or the next-door neighbor or the murderer’s mother? You might be surprised at what you discover.

References

Ashliman, DL 2023, ‘Bluebeard’, viewed 5 December 2024, <https://sites.pitt.edu/~dash/type0312.html#bon>.

Carter A, introduction by Zipes J 2008, Angela Carter: Little Red Riding Hood, Cinderella, and other classic tales of Charles Perrault, Penguin Books, New York.

Chevalier, J and Gheerbrant A 1997, The Penguin dictionary of symbols, Penguin books, New York.

Cooper, JC 1978, An illustrated encyclopedia of traditional symbols, Thames & Hudson, Inc., New York.

Davis S 2023, ‘They are the bones: a conversation with Kelly Link’, viewed 5 December 2024, <https://therumpus.net/2023/05/08/222038/>.

Heiner, HA 2021, ‘Bluebeard’, viewed 5 December 2024, <https://www.surlalunefairytales.com/a-g/bluebeard/bluebeard-tale.html>.

Tatar, M 1999, The classic fairy tales, WW Norton & Company, Inc., New York.

Tatar, M 2003, The hard facts of the Brothers Grimm, Princeton University Press, Princeton.

Warner, M 1994, From the beast to the blonde: on fairy tales and their tellers, Noonday press, New York.

Warner, M 2014, Once upon a time: a short history of fairy tales, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Zipes, J (ed) 2000, The Oxford companion to fairy tales: the western fairy tale tradition from medieval to modern, Oxford university press, New York & Oxford.

In From the beast to the blonde, Warner states that ‘Bluebeard is represented as a man against nature, either by dyeing his hair like a luxurious Oriental, or by producing such a monstrous growth without resorting to artifice’ (pp. 242-243).

The color blue represents revelation, contemplation, coolness, and the Void (Cooper, p. 40). ‘It is also the coldest color. Indifferent and unafraid, centered solely upon itself, blue is not of this world: it evokes the idea of eternity, calm, lofty, superhuman, inhuman even’ (Chevalier 1982). Bluebeard’s nature is hinted at with the unnatural color of his beard, which invokes a sense of fear in most who behold him.

At the time this tale was published, beards were out of fashion in the court of the Sun King. Warner notes, ‘the beard of Perrault’s villain betokened an outsider, a libertine, and a ruffian’ (p. 242). Beards are associated with strength and virility (Cooper 19). It represents the antagonist’s powerful status as well as his animalistic nature.

There is speculation that Bluebeard was modelled after Gilles de Rais, a Breton commander who fought in the Hundred Years’ War, a convicted mass murderer who ritually killed his child victims at his castle. Another historical figure linked to the tale is Conomor the Cursed, a medieval ruler of Brittany who decapitated his pregnant wife after she discovered a secret room with trophies from his previous wives, who he also murdered.

Zipes notes that, at the time of Perrault’s writing, many members of the aristocracy maintained a country estate, or family seat. The suggestion that Bluebeard has many country estates suggests he is very wealthy.

Keys are a symbol of knowledge, initiation, and mystery (Cooper, p. 90).

Perrault’s moral standpoint centers on the evils of female curiosity. Bluebeard’s wife joins a long line of mythical women (most notably Eve, Pandora, and Psyche) who succumb to curiosity in the pursuit of acquiring forbidden knowledge (Tatar 1999).

Zipes notes that the bloody key ‘points to double transgression, one that is both moral and sexual’ (p. 56). Warner adds, ‘In many illustrated tellings of the story, the key looms very large indeed, a gigantic forbidden fruit, so engorged and positioned that the allusion can hardly be missed’ (1994, p. 244).

Blood represents life force and the soul, and spilt blood is a symbol of sacrifice (Cirlot, p. 29).

Warner (1994) notes that the allusion to Saint Anne and/or Anne of Austria, Queen of France, mother of Louis XIV. Queen Anne's devotion to Saint Anne, the legendary mother of the Virgin Mary, gave rise to the cult of Saint Anne in the 1600s. Saint Anne was popular and known as a miracle worker among the French. She was declared a patron saint to Brittany as a result and was thus a well-known figure to its inhabitants.

Illustrators of ‘Bluebeard’ often emphasis the sabre along with turban, which aligns with the popularity of the Orientalizing of European fairy tales, prompted by the publication and popularization of Arabian Nights during the reign of the Sun King (Warner 2014).

Dragoons were a class of military who fought on foot, but travelled by horse, though from around the seventeenth century they were also often hired as conventional cavalry. They were cheaper than cavalry, but more expensive (and more mobile) than foot regiments.

A mousquetaire (musketeer), as the name suggests, was a class of soldier armed with a musket (a long, muzzle-loaded gun). The Musketeers of the Guard were a military branch of the royal household, created by Louis XIII in 1622. Unlike many other regiments of the time, the musketeers were open to men from the lower classes of the French nobility, and younger, or less favoured, sons. As so many of them were young teenagers, the musketeers had, at the time of Perrault’s writing, a reputation for … let’s say for being high-spririted.

Perhaps the most famous of the musketeers, at least for modern readers, was d’Artagnan (Charles de Batz de Castelmore, 1611-1673), who joined the musketeers in 1632 and served with them—rising to the highest rank (the next highest was the king) in 1667—until his death on the battlefield at the Siege of Maastricht. This larger-than-life real-life figure has been the basis of many creative works, but perhaps none so well-known today as Alexandre Dumas’s d’Artagnan romances (The Three Musketeers [1844], Twenty Years After [1845] and The Vicomte de Bragelonne [1847-1850]).

Just in case the reader has missed the moral of the story, Perrault offers this reminder that it is the wife’s act of disobedience that caused her fall from grace. Bluebeard, (Satan) a mass murderer, stands in as both the patriarch (God) and the serpent. ‘In his double role in the fairy tale, he reflects a problem that is intrinsic to the morality tale: the Devil does God’s work, testing sinners and proving saints’ (Warner 1994).

I really love Christine A. Jones' Mother Goose Refigured translations as she gets into the nitty gritty of word choice. I liked how she pointed out the phrasing of the title implies the villain is "reducible to his beard." I do enjoy that all these endeavours enable a love match for the sister. There's a lot to unpick in the societal language.

Women take their lives in their hands when they enter a romantic relationship. Domestic violence, sometimes resulting in the woman's death, is quite common.