Collectors' items: A partial and potted history of fairy-tale collections

Issue three: fairy tale essay

Here at The Orange & Bee our focus is on building a community around our shared passion for fairy tales. We publish annotated traditional fairy tales, and contemporary work in conversation with the fairy-tale tradition, including poems, short stories, flash, and non-fiction, as well as interviews with contemporary practitioners. We also host monthly reading roundtables, and writing roundtables.

In this essay, I explore the tradition of publishing collections of fairy tales, especially two key historical approaches to collections:

The tradition of publishing tales that are collected from and intended to express something of the folk heritage of a single culture (as exemplified by the work of the Grimm brothers), and;

the tradition of publishing works from a diverse range of cultural and folkloric traditions (exemplified by the Langs’ coloured fairy books), intended to showcase both the continuity of folklore as a narrative form, and the ‘exotic’ diversity of storytelling across a broad range of cultural settings.

Between 1785 and 1789, Charles-Joseph de Mayer published the Cabinet des fées, which was a 41-volume anthology of contes, or fairy tales, stretching from the early French conteuses such as Mme d’Aulnoy and Charles Perrault, to the philosophical moralists such as Rousseau and Mme de Beaumont. Just as the final volumes of the Cabinet were being published, however, the French revolution destroyed the elaborate court culture that had provoked, and then sustained, for over one hundred years, the aristocratic fairy tale as a central storytelling practice in French culture. As Teverson notes:

By this time, however, the impetus to collect and rewrite popular traditional tales had shifted to Germany, where an alternative movement was underway, sparked, in part, by an anxiety about the dominance of French fairy-tale models, and motivated by a desire to recover “authentic” German tales that might reflect an “authentic” German identity (2013, p. 62).

By far the most famous and enduring response to this desire to recover ‘authentic’ German stories and culture was the Grimm brothers' Kinder- und Hausmärchen, though it was by no means the only work of its kind, or even the only work produced by the two brothers as part of the larger nationalist project (they also published collections of legends and myths, grammars and—though they died with the work incomplete—a German dictionary).

Between 1805 and 1808, German Romantic authors Clemens Brentano and Achim von Arnim published a collection of folk songs in their multi-volume collection Des Knaben Wunderhorn: Alte Deutsche Lieder (The Boy’s Magic Horn: Old German Songs). The collection was intended to be an expression of authentic German culture, sufficient to promote the Gesundung der Nation (Recovery of the Nation). Despite this goal, Brentano and Arnim did not feel the need to ensure that the songs they published were actually traditional tales, or traditional German tales. Instead, many of the poems, or lieder, that they included were their own original creations. All of the songs were edited and often substantively rewritten to conform to both contemporary ideas about poetry (including preferences for rhyme and meter), and an idealised, German Romantic Naturpoesie, or folk style.

Jacob Grimm had contributed some songs to the second and third volumes of Wunderhorn, and Brentano asked the brothers if they would collect some volksmärchen (folk tales) for a future collection of prose works he was considering putting together. The project was to be similar in scope, scale, and approach as the Wunderhorn: a collection of works for an audience of adult and largely scholarly or literary-minded German readers—nationalists hungry for works that expressed a German cultural tradition they could celebrate with pride.

The works collected were to be volksmärchen, but Brentano’s and Arnim’s criteria for what might be deemed German folk tales were more flexible than those of modern folklore scholars! They were just as interested in inventing a narrative tradition as they were in recording or documenting a pre-existing oral or folk tradition of storytelling.

The Grimms enthusiastically accepted the invitation from Brentano and, from 1806, began collecting tales from friends, family, neighbours, and other sources. Arnim abandoned the project in 1809 and handed it over to the brothers, who had already shared about sixty tales with him. The brothers had a slightly different approach to the project than Brentano. Jacob, in particular, wanted the collection to be more truly a record of a pre-existing oral and folk culture than Brentano’s prior publications.

The first edition of the first volume of the KHM went to press in December 1812 and included 86 numbered tales from various sources: two supplied to them by a fellow scholar (Otto van Runge); a handful collected from a retired Captain of the Dragoons, who traded the stories for used clothing; more than 20 tales collected from the Wild family (the Grimms’ neighbours in Kassel, including Wilhelm’s future wife, Dortchen), and more than 20 from the Hassenpflug family (a wealthy family of sisters and brothers from Kassel, very educated and cultured, politically engaged and well-read), as well as 15 tales adapted from previously published sources.

In the introduction to the first edition, the Grimms refer to what Harries describes as the ‘complex’ tradition of fairy tales as practiced by French aristocratic women of the seventeenth century, comparing the women’s works unfavourably to those of Charles Perrault, who (they write) employs the proper ‘naive and simple manner’ in his tales, and doesn't embellish his tales with digressions, rich descriptions, etc. They write:

France must surely have more [fairy tales] than those given us by Charles Perrault, who alone still treated them as children’s tales (not so his inferior imitators, Aulnoy, Murat); he gives us only nine, certainly the best known and also among the most beautiful (cited in Tatar 1987, p. 209).

Here, we have a concise and revealing example of how the Grimms’ German Romantic and political ideas about folklore, including the fairy tale, led them to either misrepresent or actively remodel the genre, and its history. While, as we know, earlier fairy tales (such as those written by Aulnoy and Murat …) were told, written/transcribed, and published for adults, and were mostly digressive, playful, political, often politically subversive, and far from either naive or simple, the Grimms here argued that fairy tales were by definition like their own preferred, and at least partly self-created, fairy-tale form: compact, morally simplified, imitative of an imagined voice of the common or peasant folk, and presented as a written version of a prior oral storytelling text or tradition.

[Note also the erasure of the role of women as leading figures in the history of the fairy tale. d'Aulnoy, far from being an ‘imitator’ of Perrault, was the author of what is widely considered the first literary fairy tale written in France, ‘L'ïle de la félicité’, which was embedded in her novel, Histoire de Hypolite]

The rabbithole: were the Grimms frauds or heroes?

We could, here, go down a fascinating rabbit hole, attempting to determine which (if any) of the works collected and published by the Grimms in the KHM were previously oral texts, texts shared among the common or peasant folk, or even authentic in terms of their belonging to German culture. The story of how the brothers collected their works, and from whom, and then selected, edited (over many editions), and revised the tales, as well as how they presented them as authentic expressions of a long-lived German culture, is a fascinating one. If you do want to go down that particular rabbit hole, I recommend starting with two key works.

Heinz Rölleke: re-assessing the Grimms sources

Firstly, the work of Heinz Rölleke, who was the first scholar to critically examine the claims made by the Grimms in their prefaces and introductions, letters, and other paratexts—and the claims of their descendants and followers—and compare them to the archive of their materials, including the 1810 Olenberg manuscript (an early, unpublished manuscript of the KHM) and the Grimms’ own notes. Rölleke’s work was enormously influential in the 1970s and 1980s, and resulted in a widespread reassessment of the myth that the Grimms had collected their fairy tales directly from the peasantry, and then published the tales that they had collected in an unadulterated state.

John M Ellis: the Grimms as fakers and forgers

Secondly, John M Ellis’s One fairy story too many (1983) caused a sensation when it was first published. Ellis argues that the Grimms deliberately and carefully misrepresented their sources, as well as their collecting and editing processes. Ellis argued that the Grimms’ work was equivalent to that of James Macpherson: the inventor of the fake ancient Gaelic poet, Ossian. He wrote that:

The Grimms never bothered to collect material of real quality, lied to their public about its nature and their sources, destroyed their basic material, and again lied about the extent of their own role in creating the text which they published, that role being rather more active than Macpherson’s had been. Yet Macpherson generally counts as the faker and forger, not the Grimms (Ellis 1983, p. 98).

Fairy tales as children’s stories

When the first editions of the KHM were published, they were not intended to be read by children. Like the folk song collections published by Brentano and von Arnim, the intended audience for the first edition of the KHM were scholars of German literature and culture: adults interested in identifying, collecting, preserving, and analysing evidence of an ongoing, historical, and authentic German folk culture. Arnim, however, identified the collection’s potential appeal to children, and worried that the first edition was too scholarly and dull. Brentano, too, thought the stories were dull and underworked—not ‘improved’ and made more palatable to contemporary readers, like the folksong collections he and Arnim had published. Others who reviewed the work publicly, and in private correspondence, also worried that the stories were too frightening and violent, promoted dangerous and outdated superstitions, and presented a vision of German culture that was often troubling, and very much at odds with the idealised national identity the Grimms, and many others, sought to ‘recover’ and celebrate through their work.

Nevertheless, the publication (eventually and mostly in its later, revised forms) eventually gained a popular audience and, as later editions rolled from the presses, the Grimms—and particularly Wilhelm, who took control of the project—worked hard to make the collection more palatable for a family, and then for an explicitly child, audience.

Wilhelm reworked the stories over and over again in the successive editions of the KHM, not just removing the tales that lacked a clear and pure German heritage, but also reworking the stories that remained to provide them with a more consistent voice, or style—one that mimicked or performed that of an oral tale told by what he referred to as a ‘simple’ or uneducated, but nonetheless nostalgically-celebrated, peasantry. He also worked to make the tales more consistently Germanic, more morally conventional (by the standards of the time), and more aligned with contemporary notions of justice and punishment.

As part of this project of updating the collection and producing more popular editions, the Grimms produced the so-called small editions (Kleine Ausgabe) of the KHM, which included just 50 of the most popular stories, and were illustrated by various artists, including Ludwig Grimm. These collections—shorter, less violent, more palatable to a non-specialist, non-adult readership—became ubiquitous in the nineteenth-century German nursery, where, according to Teverson, ‘they functioned to reinforce conventional ideas about family, about German cultural identity and about society’ (2013, p. 67).

It was these small editions that were widely translated and distributed throughout Europe, and in particular in Britain and the colonies. In the process of translation and republication, the Grimm tales were often further bowdlerised and condensed. Tales that had once been morally complex or ambivalent, explicitly violent and illogical, or at least irrational, became increasingly popular: known principally only through these more compressed, flattened, morally simplified and often beautifully illustrated editions.

What had once been tales collected by two scholars as evidence of an authentically German folk culture for other scholars, and adult German readers, became—through a complex series of processes of production, negotiation, editing, republishing, reviewing, criticism, translation, and so on—works that were equally mere entertainment, and moral educational materials, for a generically white or Western-European child readership.

Equally, what had once been faithfully transcribed records of an oral folk tradition (though Rölleke’s work, in particular, revealed how inaccurate this persistent myth was) became known popularly as stable, literary works. Over time, the works that the Grimms collected, edited, and published, and which had been understood as authentically folkloric in being subject to transmission and variation through informal culture—as being true folklore—became understood, particularly in popular culture, as increasingly canonical, culturally decontextualised or ‘generic’, and unvarying, or stable. In other words, these stories that had once been clear examples of a folklore as a narrative tradition, became increasingly atypical: literary, stable, and canonical. Though, interestingly, critics, scholars and readers alike remained in general agreement that these were Buchmärchen—what are sometimes referred to in English as orature; that is, oral tales with folk elements that have been written down and printed—rather than Kunstmärchen: invented or literary tales.

The Grimms’ tales do have elements of folk tradition—the Grimms were not quite as laissez-faire about the authenticity of their collecting practices as Ellis has suggested—but they were extensively shaped and codified by a process of writing, storytelling, editing, collecting, translation, and other forms of sharing and re-sharing narratives that included the Grimms, but also extended well beyond them. To give just one example: ‘Rapunzel’ is tale number twelve in the Grimms’ KHM. Their source was a short story published by Friedrich Schulze in his Kleine Romane in 1790 (so … not a peasant woman telling tales by the fireside). Schulze’s tale was a literary and German translation and adaptation of Charlotte Caumont de la Force’s tale ‘Persinette’, which had been first performed in a literary salon—part of the aristocratic oral tale-telling culture of late seventeenth-century Paris—and then written down and published, in a slightly altered version, in 1697. ‘Persinette’ was itself a translation and adaptation of an earlier story included in Giambattista Basile’s Lo cunto de li cunti, which was published after Basile’s death, between 1634 and 1636. The tale has even older precedents, including medieval romances and the mythic narrative of Saint Barbara.

For a long time—up until as recently as the 1970s—folklorists mostly understood fairy tales as a genre of narratives that had moved, slowly and incrementally, from purely oral folk narratives, into transcribed literary forms. And, in doing so, moved from the mouths and ears of the ‘folk’ (usually understand as the lower, working or peasant classes), to the educated and elite: first, as audience, and then later as re-tellers. This understanding has changed over time, including through vital reconsiderations of the claims that the Grimms made about their editorial processes. As Harries writes:

It seems that we may have the direction of transmission wrong: rather than moving from the folk to the elite, the fairy tale may at least as often have moved in the other direction, from writing, to oral tale-telling (Harries 2001, p. 78).

Cross-cultural collections: the Lang coloured fairy books

To bring together a collection of pre-existing narratives is to subtly transform the meaning of those individual items, including by sometimes changing the genre of the works (since genres are often culturally constructed and mediated) as well as by changing the intended audience for the individual works.

For example, the audience for a single tale collected by an anthropologist from an Indigenous person in Australia in the 1800s, and then published in a scholarly journal of anthropology, might initially have been the (white) anthropologist and their peers (with an assumption that the prior audience/s for the story were other Indigenous peoples, and not just the white anthropologist who has asked for a story to take home with them, as souvenir or artefact). However, when that tale is selected, translated, edited, and (re)published in a lavishly produced and illustrated collection of English-language international fairy tales and folklore, by a British publisher, the audience is no longer members of the Indigenous culture from which the tale was ‘collected’, or Victorian anthropologists, but white British families, and in particular their children.

Often, as folklore and other fairy-tale works were selected and edited in order to become part of collections, changes in their genre and audience are at least partly reflected in changes not just to how the works are framed, but also to the structure, tone, style, and even implied or imposed themes of the tales.

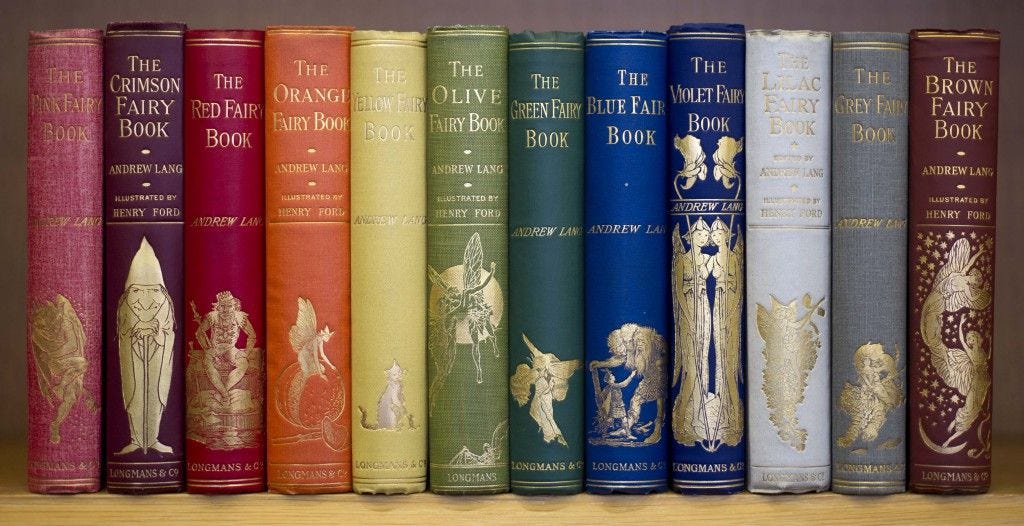

Between 1889 and 1910, Andrew Lang published a series of twelve fairy books (with substantial support from many other editors and translators, including his wife, Leonora Lang. In fact, many researchers now argue that a large part of the work of producing the books was done by Leonora). The books were lavishly produced, with gilt edges and embossed leather or linen covers. They included both coloured and black-and-white illustrations.

One of the most striking features of Lang's coloured fairy books is their focus on the inclusion of works collected from various cultures. While the Grimm brothers aimed to collect and publish evidence of an authentic and long-lived oral and material German culture, Lang aim was to collate tales from various cultures throughout the world, both as evidence of the cross-cultural nature of folkloric storytelling as a cultural practice (emphasising continuity and sameness), and as evidence of the strangeness and exoticism of ‘other’ (non-British, and especially non-European) cultures and stories.

What we might now call ‘multicultural’ literary collections or anthologies, particularly of folklore, became common in the twentieth century, but Lang’s collection was the first, and is perhaps still one of the most extensively international, collections of fairy tales. The books, in fact, became increasingly international, and what we might call inclusive, as the series developed. The Pink Fairy Book, for example, first published in 1897, contains stories from Italy, Japan, and Africa. The last seven coloured fairy books include Armenian, Australian, Brazilian, Hungarian, Lithuanian, Portugese, Rhodesian, Russian, Serbian, Swahili, and Tunisian narratives.

International folklore as Christmas gifts

The twelve coloured fairy books were each published during what was, at the time, the emerging Christmas shopping season, and were designed to appeal to people shopping for gifts for their families. In Some patterns and trends in British publishing 1800–1919, Eliot notes that the concept of the Christmas book-buying season emerged in the 1830s and 1840s (1994, p. 33). In order to appeal to the gift-buying public, most of the coloured fairy books were published with gilt edges and, starting with The Violet Fairy Book, each book contained eight coloured plates, as well as numerous internal black-and-white illustrations (all by the same illustrator: Henry Justice Ford). According to Sara Hines:

The correlation between Lang’s collection and Christmas is particularly poignant for three reasons. The first reason is that much of the Christmas holiday season is a Victorian invention. The second reason for the association of Lang’s collection and Christmas is that Christmas, as it has developed since the Victorian period, has become a time of nostalgia. Accordingly, not only does the publication of Lang’s books at Christmas correspond to the historical development of the commercial Christmas market, but the series also conveys a longing for the past, whether the twentieth-century’s nostalgia for Victorian England or the Victorian nostalgia for the lost ‘once upon a time’ in fairy tales.

The third significant connection between Lang’s collection and Christmas is the suggestion of home implicit in both. Christmas is a time for family ... [and] Lang’s books convey this same sense of home, family, and nation. The books, as gifts, contain stories from a diverse range of places, peoples, and cultures, but these are stories that are meant to be read from the safety and security of the British home (Hines 2010, pp. 52-53).

'Outlandish native stories' for British children

According to the preface of The Brown Fairy Book:

The stories in this Fairy Book come from all quarters of the world. For example, the adventures of ‘Ball-Carrier and the Bad One’ are told by Red Indian grandmothers to Red Indian children who never go to school, nor see pen and ink. ‘The Bunyip’ is known to even more uneducated little ones, running about with no clothes at all in the bush, in Australia. You may see photographs of these merry little black fellows before their troubles begin, in ‘Northern Races of Central Australia,’ by Messrs. Spencer and Gillen. They have no lessons except in tracking and catching birds, beasts, fishes, lizards, and snakes, all of which they eat. But when they grow up to be big boys and girls, they are cruelly cut about with stone knives and frightened with sham bogies—‘all for their good’ their parents say—and I think they would rather go to school, if they had their choice, and take their chance of being birched and bullied. However, many boys might think it better fun to begin to learn hunting as soon as they can walk. Other stories, like ‘The Sacred Milk of Koumongoé,’ come from the Kaffirs in Africa, whose dear papas are not so poor as those in Australia, but have plenty of cattle and milk, and good mealies to eat, and live in houses like very big bee-hives, and wear clothes of a sort, though not very like our own. ‘Pivi and Kabo’ is a tale from the brown people in the island of New Caledonia, where a boy is never allowed to speak to or even look at his own sisters; nobody knows why, so curious are the manners of this remote island. The story shows the advantages of good manners and pleasant behaviour; and the natives do not now cook and eat each other, but live on fish, vegetables, pork, and chickens, and dwell in houses. ‘What the Rose did to the Cypress’ is a story from Persia, where the people, of course, are civilised, and much like those of whom you read in ‘The Arabian Nights.’ Then there are tales like ‘The Fox and the Lapp’ from the very north of Europe, where it is dark for half the year and daylight for the other half. The Lapps are a people not fond of soap and water, and very much given to art magic. Then there are tales from India, told to Major Campbell, who wrote them out, by Hindoos; these stories are ‘Wali Dâd the Simple-hearted,’ and ‘The King who would be Stronger than Fate,’ but was not so clever as his daughter. From Brazil, in South America, comes ‘The Tortoise and the Mischievous Monkey,’ with the adventures of other animals. Other tales are told in various parts of Europe, and in many languages; but all people, black, white, brown, red, and yellow, are like each other when they tell stories; for these are meant for children, who like the same sort of thing, whether they go to school and wear clothes, or, on the other hand, wear skins of beasts, or even nothing at all, and live on grubs and lizards and hawks and crows and serpents, like the little Australian blacks.

The tale of ‘What the Rose did to the Cypress’, is translated out of a Persian manuscript by Mrs. Beveridge. ‘Pivi and Kabo’ is translated by the editor from a French version; ‘Asmund and Signy’ by Miss Blackly; the Indian stories by Major Campbell, and all the rest are told by Mrs. Lang, who does not give them exactly as they are told by all sorts of outlandish natives, but makes them up in the hope white people will like them, skipping the pieces which they will not like. That is how this Fairy Book was made up for your entertainment (Lang 2009, pp. vii-viii).

The coloured fairy books, in other words, were a mechanism through which white, Victorian-era British editors and translators collected, possessed, altered, and displayed the empire through ownership of and authority over ‘outlandish native stories’. The collections certainly contain stories of other places, peoples, and cultures, but the stories have been collected, translated, and edited specifically so that they are palatable for white British people, in particular white British children, and are intended to be read within the safety and security of the British home. The cultures, peoples and narratives in the Lang works are, according to Hines, ‘no longer the exoticized Other, but instead have been transformed, brought home, and colonized’ (2010, p. 54).

In the nineteenth century, Lang's coloured fairy books were also typical, in some ways, of a continuation of the process that had been so strongly a part of Wilhelm Grimm's editing and re-editing of the KHM tales: a process of purifying and simplifying oral folkloric narratives, transforming them into fairy tales that were considered suitable for their new, presumed innocent, and very young, readers. Violence, irrationality, sex, digressive narration, bawdiness, subversiveness, politics and social critique, were winnowed out of the tales that the Langs’ published, and thereby—as a significant player in both the popularisation and codification of fairy tales—out of the genre more generally.

What remained—what was kept—was a notion that fairy tale was (and had always been) a genre made up of ‘compact’ forms, suitable largely for the entertainment and moral education of (very) young children, and evidence (or ‘survivals’) of a long-lost and much-grieved oral storytelling tradition and, often, the culture from which the stories were collected.

A continuing tradition

Fairy tales continue to be published and re-published in collections, both for children and for adults, for scholars and for more general readerships. In this essay, I’ve explored some of the ideological and political influences on both the Grimms’ and the Langs’ collections. But there are so many more collections, and types of collections, we could consider!

What do you make, for example, of The Allies’ Fairy Book, published in 1916, and including thirteen stories understood to be drawn from eleven allied nations of the First World War (Belgium, England, France, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Portugal, Russia, Serbia, Scotland, and Wales)? This book was one of several collections of tales published during the early years of the First World War, including The navy book of fairy tales, and Edmund Dulac’s fairy book: Fairy tales of the allied nations. These wartime collections, and their fellow stand-alone works of fairy-tale literature1, are a fascinating cultural phenomenon, deeply reflective of the political and social concerns of their time and place. As Lucy Shaw writes in an article for the V&A blog:

[The Allies’ Fairy Book] is inextricably linked to its historical context, intertwining folklore with the rising nationalism of the period. Published to give what Gosse calls “national identity” to each country fighting on the British side during the War, the impetus of the book was to support the propaganda effort and inspire patriotism through folklore (Shaw 2019, np).

I wonder: what collections of traditional fairy tales inhabit your shelves? And in what ways do those collections reflect contemporaneous and/or historical ideas about what fairy tales are, who reads them (or should read them!), and why?

References

Basile, G 2016, Giambattista Basile's Tale of tales, trans. Nancy Canepa, New York, Penguin.

Black, BJ 2000, On exhibit: Victorians and their museums, Victorian literature and culture series, Charlottesville, University Press of Virginia.

Eliot, S 1994, Some patterns and trends in British publishing, 1800-1919, London, Bibliographical Society.

Ellis, JM 1983, One fairy story too many: the brothers Grimm and their tales, Chicago, University of Chicago Press.

Grimm, J & W 2007, The Complete Fairy Tales, J Zipes (trans., ed.), London, Vintage Books.

Harries, EW 2001, Twice upon a time: women writers and the history of the fairy tale, Princeton, Princeton University Press.

Hines, S 2010 ‘Collecting the empire: Andrew Lang’s fairy books’, Marvels & Tales, vol. 24, no. 1, pp. 39-56.

Lang, A (ed) 2009, The brown fairy book, New York & London, Longmans, Green and Company, viewed 1 March 2022, <https://archive.org/details/brownfairybook00lang_2/page/n9/mode/2up>.

Lang, A (ed) 2009, The green fairy book, London, Longmans, Green, and Company, viewed 1 March 2022, <https://archive.org/details/greyfairybook00fordgoog>.

Rölleke, H 1988, ‘New results of research on Grimms' fairy tales’ in J McGlathery (ed) The brothers Grimm and folktale, Urbana, University of Illinois Press, pp. 101-111.

Tatar, M 1987, The hard facts of the Grimms’ fairy tales, Princeton, Princeton University Press.

Teverson, A 2013 Fairy tale, London & New York, Routledge.

See, for example, Eleanor Gray’s The war fairies (1917)—a short verse narrative in which the fairies Viola and Mignon become mortal (giving up fairy immortality) in order to stop the war by ‘weav[ing] chains of love throughout the lands, binding all equally in bonds of brotherhood’. There’s also Rose Patry’s Britain’s Defenders, Or Peggy’s Peep into Fairy Land (1917), a story in which the fairy Queen, Britannia, calls on the wind, sun and rain to aid the fairy folk and humans in defeating the Germans.

I learned so much! And I added a book to my wishlist (One Fairy Story Too Many) and removed Lang’s colorful series from my list. They’re no longer appealing to ‘complete my collection’ now that I understand how ‘inauthentic’ they are as cultural stories.

My favourite international collection is Angela Carter’s. Some of my favourite tales I discovered there. And as far as I can tell she kept them as close to how they were told as she could- including writing in English dialects that may sound charming to be heard but are hard to read lol

Thank you for your beautiful, informative essay. As a child, I was surrounded by fairy tales...books of them, usually in beautiful color..."Cinderella," Sleeping Beauty," "Beauty and the Beast," "Goldilocks and the Three Bears," and dozens more. By the time I could read, I wrote my own, filling notebooks of tales of dragons and persecuted princesses and knights on horses (white horses, of course). I never followed up on the history of these tales, but I think they affected the color of my life..