Once upon a time there was an apple, a mirror, a key, a ring, a rose, a witch, a wolf, a cottage, a crown. And in that far away land, just past the dark forest, lived beautiful princesses, heroic girls, talking animals, brave tailors, and beastly bridegrooms—all fated to live happily ever. The evil queens, ugly stepsisters, sly wolves, stupid ogres, and crippled dwarves get what’s coming to them. Or so the stories go.

Yet there is a darker side to fairy tale, a realm under the hill where silver trees bear jewelled fruit and masked dancers trace the patterns of an enchanted faery reel. In these stories, Sleeping Beauty wakes to twins suckling at her breasts, Donkeyskin flees from a father’s unnatural lust, Cinderella’s stepsisters are mutilated and then blinded, the Little Mermaid’s tongue is cut from her mouth, Little Red Riding Hood slips into bed with the wolf, and Bluebeard stores his murdered wives in the cellar. The narratives here are not for children, nor were they ever meant to be.

In Once upon a time: A short history of fairy tale (2014), scholar Marina Warner describes the history of fairy tale as a map. (Nike Sulway’s excellent essay ‘Collectors' items: A partial and potted history of fairy-tale collections’ in Issue 3 of The orange & bee is a perfect place to start your own personal exploration of traditional collections.) However, even though fairy tales might appear to be firmly rooted in place, they ‘migrate on soft feet, for borders are invisible to them’ (Warner 2014).

A fairy tale keeps on the move between written and spoken versions and back again. The circle loops out across the centuries, forming a community across barriers of language and nation as well as time. The stories’ interest isn’t exhausted by repetition, reformulation, or retelling, but their pleasure gains from the endless permutations performed on the nucleus of the tale, its DNA as it were (Warner 2014).

Many of the earliest examples of fairy tales were collected as folk songs, such as those included in the multi-volume collection Des knaben wunderhorn: alte Deutsche lieder (The boy’s magic horn: old German songs) collected by German Romantic authors Clemens Brentano and Achim von Arnim between 1805 and 1808. Jacob Grimm’s contribution to the second and third volumes eventually led to the collections of volksmärchen (folk tales) published by the Brothers Grimm in Children's and household tales (Kinder- und Hausmärchen) between 1812 and 1857.

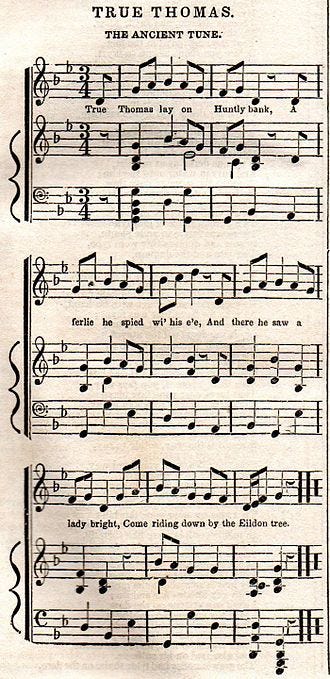

When it comes to fairy tales and folklore presented in verse, another prominent example is the ten-volume opus The English and Scottish popular ballads (1882–98) collected by American folklorist Francis James Child. This collection of 305 folk songs is colloquially known as the Child Ballads, and, like the Grimm Brothers’ fairy tales, they record stories of murder and monsters, grief and guilt, brides and beasts. This examination of song only supports the strong foundational connection between fairy tales and poetry. For instance, the Child Ballads include ‘Tam Lin’ (Child 39), a familiar story about a mortal man rescued by his lover from the Faerie Queen. Another popular song included in the index is ‘The twa sisters’ (Child 10), a macabre song about sisterly rivalry, a bone harp, and retribution. This particular murder ballad has inspired more than 500 versions, as recorded in the Roud Folk Song Index. These endless variations exemplify the mutability of oral traditions and their translation to poetic forms.

In addition to folk songs, the supernatural world of Faerie also showed up in formal verse. Poets including Percy Bysshe Shelley (‘Queen Mab’ 1813), Samuel Taylor Coleridge (Christabel 1816), and John Keats (‘La belle dame sans merci’ 1819 ) explored the supernatural during the Romantic era. But when it comes to fairy lore, the Victorians were even more dedicated in their pursuit.

Perhaps one of the most well-known fairy tale poems from this period is Christina Rossetti’s ‘Goblin market’, which was first published as part of her collection Goblin market and other poems in 1862. This long, narrative poem tells the tale of two sisters, Laura and Lizzie, who are tempted by goblin men selling fairy fruit.

We must not look at goblin men, We must not buy their fruits: Who knows upon what soil they fed Their hungry thirsty roots? (Rossetti)

Laura succumbs, and Lizzie has to endure dangerous ordeals to bring her sister back from the brink of death. This type of tale is a familiar one. Although it is an original tale, Rossetti’s ‘Goblin fruit’ springs from folkloric traditions concerning the seductive dangers of fairyland. Another excellent example of a poem using the theme of fairy abduction is ‘The stolen child’ (first published in 1889) by WB Yeats.

Rhyme, repetition, rhythmic prose or verse carry traces of oral performance and act as mnemonic markers. They also draw attention to the teller, who frequently opens and closes with a set phrase in order to frame as fairy tale what the audience is about to hear and help us enter the world where magical thinking rules. In this way, the storyteller adopts the devices of verbal magic; the animate forces ascribed to the world of phenomena by fairy tale as a genre are infused into the individual stories themselves’ (Warner 2014).

No wonder poets turn to fairy tales for inspiration. What better way to continue the tradition of oral folklore than by threading these tales in poetic form?

In 1971, American poet Anne Sexton offered a scathing critique of contemporary portrayals of fairy tale heroines with the publication of Transformations (1971). This collection includes seventeen retellings drawn from the Brothers Grimm including ‘Snow White and the seven dwarfs’, ‘Rumpelstiltskin’, ‘Rapunzel’, ‘Cinderella’, ‘Red Riding Hood’, and ‘Briar Rose (Sleeping Beauty)’. The less familiar tale ‘The golden key’ closes Grimm’s fairy tales (1815), so perhaps it’s unsurprising that this is the story Sexton uses to open Transformations:

The speaker in this case is a middle-aged witch, me— tangled on my two great arms, my face in a book and my mouth open wide, ready to tell you a story or two (Sexton 1971).

Instead of lingering in the distant and detached world of Faerie, these poems take on a contemporary tone with mundane references to the modern world. Snow White has cheeks ‘as fragile as cigarette paper’; Iron Hans is transformed ‘[w]ithout Thorazine / or the benefit of psychotherapy’; and Cinderella’s rags-to-riches is echoed in a tale of a nursemaid who lands an heir: ‘From diapers to Dior. / That story’ (Sexton 1971). Sexton spins new life into these familiar yarns. She makes them her own.

Another collection that laid the groundwork for growing field of modern fairy tale poetry is The world’s wife by Carol Ann Duffy (1999). These themed poems draw from fairy tales and myth in a feminist exploration of gender roles and the treatment of women in mythical, folkloric, and historical contexts. Duffy subverts stereotypes with a poetic voice that ranges from dramatic monologue to balladesque authority. She urges readers to re-examine cultural conventions and preconceived expectations. When the wolf steps on the path, the girl will surely follow. But why? Duffy explains the motivation behind her decision in ‘Little Red-Cap’:

Here’s why. Poetry The wolf, I knew, would lead me deep into the woods Away from home, to a dark tangled thorny place Lit by the eyes of owls (Duffy 1999).

This is where the transformation begins.

International interest in fairy tale poetry steadily grew in the early 2000s, partly supported by and reflected in The journal of mythic arts (1998-2008), an online journal edited by folklorist, author, and editor, Terri Windling. This selection of fairy tale and mythic poetry includes work by such luminaries as Neil Gaiman, Holly Black, Charles de Lint, Margaret Atwood, Veronica Schanoes, Mario Milosevic, Jeannine Hall Gailey, and Theodora Goss.

Also featured in the Journal of mythic arts, Jeannine Hall Gailey looks at fairy tales through a feminist lens, and many of these poems ended up in Becoming the villainess (2006). Gailey is unapologetic as she strips away the veneer of tired tropes ranging from classic mother-daughter conflict to the image of beautiful dead girls. Readers eavesdrop on the mundane and the magical as Gailey explores the inevitable transformation from hero girl to wicked witch.

Fast forward a decade, and Instapoet Nikita Gill takes this a step further in Fierce fairytales: poems & stories to stir your soul (2018). A quick glance at the poems’ titles reveals the contemporary and feminist approach in Gill’s reimagings: ‘Why Tinkerbell quit anger management’, ‘Lessons in surviving long-term abuse’, ‘Two misunderstood stepsisters’, ‘How you save yourself’, and ‘Take back your fairytale’. Gill celebrates witches and crones. She subverts gender stereotypes. And she encourages self-empowerment. ‘Await no princes to save you / through their lips touching yours / whilst you are in unwilling slumber’, Gill urges to the classic characters Snow White and Sleeping Beauty; ‘Darkling magic is coursing through those veins, / turn it into kindling, my resourceful girls, / find one another in the fog realm, / wake each other up instead.’

Not only are these fairy-tale poems being published, but they are winning awards. Theodora Goss collected eight stories and twenty-three poems in Snow White learns witchcraft (2019), which won the 2020 Mythopoeic Fantasy Award for Adult Literature. Christina Sng is a two-time Bram Stoker award-winning poet of A collection of nightmares (2017) and A collection of dreamscapes (2020). Poems centered on fairy tales and myth continue to receive acclaim and interest. Like so much of the world around us, these wonder tales often defy prediction or logic while remaining rooted deep in the collective unconscious. These tales provide a wealth of material that can be stripped, pummeled, reassembled, and yet still retain a sense of familiarity that keeps readers returning for more.

In Seven miles of steel thistles: reflections on fairy tales, scholar and author Katherine Langrish writes about the enduring popularity of fairy tales:

They’ve been told and retold, loved and laughed at, by generation after generation because they are of the people, by the people, for the people. The world of fairy tales is one in which the pain and deprivation, bad luck and hard work of ordinary folk can be alleviated by a chance meeting, by luck, by courtesy, courage and quick wits—and by the occasional miracle. The world of fairy tales is not so very different from ours. It is ours (2016).

Note: Sections of this essay previously appeared in the essay ‘Into the dark wood: fairy tale poetry’, in Writing poetry in the dark, edited by Stephanie M. Wytovich, Raw Dog Screaming Press, 2022).

References

Duffy, CA 1999, The world’s wife, Farrar, Strauss & Giroux, New York.

Gaiman, N 2000, ‘Instructions’, Journal of mythic arts, viewed 1 January 2025, <https://endicottstudio.typepad.com/poetrylist/instructions-by-neil-gaiman.html>.

Gill, N 2018, Fierce fairytales: poems & stories to stir your soul, Hachette, New York.

Goss, T 2019, Snow White learns witchcraft, Mythic Delirium, New York.

Hall Gailey, J 2006, Becoming the villainess, Steel Toe Books, Bowling Green.

Langrish, K 2016, Seven miles of steel thistles: reflections on fairy tales, Greystones Press, Oxfordshire.

Rossetti C nd, ‘Goblin market’, Poetry Foundation, viewed 1 January 2025, <https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44996/goblin-market>.

Sexton, A 1971, Transformations, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, Boston.

Sng, C 2017, A collection of nightmares, Raw Dog Screaming, Bowie.

Sng, C 2020, A collection of dreamscapes, Raw Dog Screaming, Bowie.

Yeats, WB nd, ‘The stolen child’, Poets.org, New York, viewed 1 January 2025, <https://poets.org/poem/stolen-child>.

Warner, M 2014, Once upon a time: a short history of fairy tale, Oxford University Press, Oxford & London.