Here at The Orange & Bee our focus is on building a community around a shared interest in (passion for!) fairy tales. We publish annotated traditional fairy tales, and contemporary work in conversation with the fairy-tale tradition, including poems, short stories, and non-fiction, as well as interviews with contemporary practitioners. We also host monthly reading roundtables, and writing roundtables. All with strong links to the fairy-tale tradition.

In this essay, I want to explore a few different definitions of traditional fairy tales. (As opposed to contemporary fairy tales, or contemporary works that draw on the fairy tale tradition).

Folklore and fairy tales

One way of understanding or defining traditional fairy tales is as a form of folklore, and in particular as a form of folklore narrative. Folklore narratives are a sub-set of the much larger and more diverse body of folkloric cultural practices and artefacts. In very simple terms, folklore is ‘artistic communication among small groups’ (Ben-Amos 2014, p. 18), and folklore narratives are the subset of those communications that are stories, or narratives.

Folklore can include a whole range of things, from recipes and dances, to kissing games and rituals. Folklore includes customs (what we do), beliefs (including religious beliefs), material culture (food, vernacular architecture, decorative crafts, and so on), and narratives.

In Living folklore: an introduction to people and their customs, Martha Sims and Martine Stephens define folklore a little more comprehensively than Ben-Amos, and give us a broader picture of the range of folkloric practices. Sims & Stephens write that:

Folklore is informally learned, unofficial knowledge about the world, ourselves, our communities, our beliefs, our cultures and our traditions, that is expressed creatively through words, music, customs, actions, behaviors, and materials. It is also the interactive, dynamic process of creating, communicating, and performing as we share that knowledge with other people (2005, p. 8).

Because fairy tales are incredibly difficult to define, and because the different genres of folkloric narratives often overlap, it’s useful to think about fairy tales in relation to other folklore narratives, which is what we’ll do here soon. In this essay, I explore four key genres of folklore narrative by offering a brief definition of each, and considering the relationship of each genre to notions of truthfulness (a neat and handy way to consider the similarities and differences between them). I also consider their role in their culture/community.

But, before I talk about the four key folklore genres, I want to focus on two things that folklore narratives have in common: they exist in both oral and literary forms, and they exist in various versions and variants.

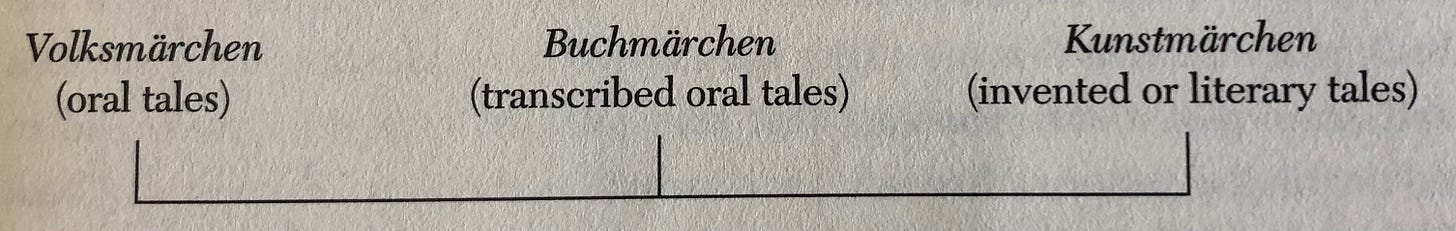

Volksmärchen, Buchmärchen, Kunstmärchen

Folklore narratives exist in a range of forms, but the two dominant or distinct forms are oral and literary. That is: folklore narratives (including fairy tales) are usually either oral (told or performed), or literary (written or printed texts).

Unlike many other folklore and fairy tale scholars, Maria Tatar describes folktales as exclusively oral tales, asserting that:

the term folktale traditionally has been used in two senses. One the one hand, folktale refers to oral narratives that circulate among the folk; on the other it designates a specific set of tales, namely oral narratives that take place among the folk, that is, in a realistic setting with naturalistic details (2019, p. 33).

However, the German term for works like those in the Grimms’ KHM is Buchmärchen. Buchmärchen are traditional oral folklore narratives that have been transcribed: that is, that have been recorded in some form, and then written down or printed.

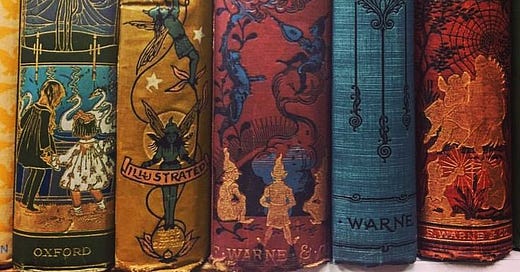

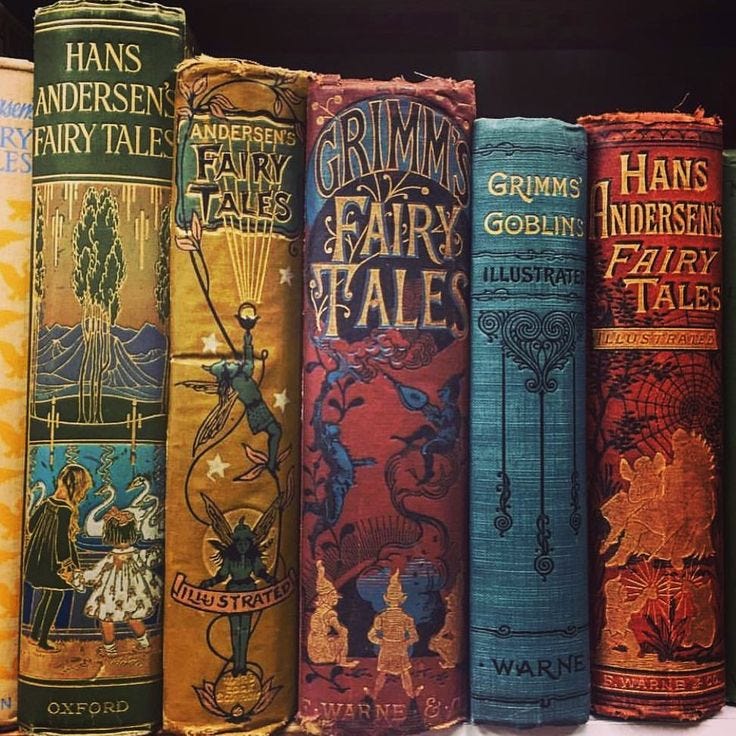

Buchmärchen constitute most of the traditional tales that we read, share, and study: those collected, transcribed, translated, and edited, perhaps annotated, then published in books as diverse as the Grimms' KHM, the Lang's coloured fairy books, Joseph Jacobs's English Fairy Tales, Ozaki's Japanese Fairy Tales, Afanasyev's Russian Fairy Tales, or Asbjørnsen and Moe's Norske folkeeventyr (Norwegian Folk Tales).

Voksmärchen are folk narratives as they existed in their ephemeral oral form. While we can infer their existence and characteristics from transcribed versions, we don’t have access to them any more. This is particularly true of tales that may have been told and retold many times, in many places, and over many generations, but were—for whatever reason—never ‘recorded’, never transformed into Buchmärchen.

The tales of Basile, Perrault, and d'Aulnoy (and the other conteuses of seventeenth-century France), as well as writers like Hans Christian Andersen, were not the work of fairy tale collectors and editors, but of writers who drew on the motifs and imagery, even the narrative shapes of traditional folklore narratives, but created literary works for which they claimed authorship. The tales that they wrote, presented, and published are Kunstmärchen.

These three forms of folklore narratives make explicit some of the relationships between oral, transcribed, and literary fairy tales. What the neat diagram doesn’t easily show, however, is that the movement of tales between these three modes isn’t always either so neat, or so one-directional.

We know, for example, that while the Grimms often claimed that the stories in the KHM were Buchmärchen—asserting that they had simply transcribed the tales as told to them by oral storytellers—many, if not most, of the tales in the KHM were collected from literary sources. Additionally, and particularly over the various editions of the KHM, the Grimms edited the stories they collected: altering the tone or voice of some works, as well as making changes to the characters, relationships, events, and imagery. The resulting final-edition tales sit somewhere in between Buchmärchen and Kunstmärchen.

This illuminates another shared feature of folklore narratives: they travel, and are constantly being retold or rewritten. Fairy tales, and other forms of folk narrative, are told and retold, in various times and places, by various storytellers, and for various audiences, and in various forms. As they travel, as in the game of Chinese whispers, the tales are sometimes subtly, and sometimes more significantly, altered. Which brings us to thinking about tale types, versions, and variants …

Tale types, versions and variants

One of the key tools used by fairy-tale scholars to identify, compare, and critically analyse folk narratives is the ATU Index (The Aarne-Thompson-Uther Index), which is a catalogue of folklore narratives. The index is divided into various sections and sub-sections. Fairy tales, for example, are catalogued/described in the ‘Tales of magic’ section, ATU300 to ATU 749.

Aside: One way to identify fairy tales is to assert that they appear in this section of the ATU Index (300—749). This is a neat and tidy way to identify many fairy tales, but potentially means that some fairy tales that aren’t recorded in the index—particularly fairy tales from outside the European tradition—get left out of the canon).

The ATU Index is an expansion of a catalogue of Scandinavian folklore first developed by Antti Aarne, a Finnish folklorist, and later further developed and expanded, including by including and referring to a broader and somewhat more international body of folklore, by Stith Thompson (who produced the AT Index), and finally by Hans-Jörg Uther.

Each entry in the ATU Index gives the identifier of the tale type (eg: ATU451), and a brief generic title for the tale type (eg: The maiden who seeks her brothers). It then provides a very brief summary of the main features of the main variant or variants of the tale type, and ends with a list of some known versions of the tale. Within the tale summary/ies, there are often cross-references to Stith Thompson’s Motif-Index of folk literature.

The ATU Index provides an authoritative source of descriptions of the main variants of each folklore narrative it includes and is, among many other things, therefore a useful resource for assessing whether a particular iteration of a folklore narrative is a version of a known or traditional variant, or an example of a new variant. And, of course, the ATU can help you identify a tale type, and then clarify which variant of a tale type you have in your hands.

Every iteration of a folklore narrative that you encounter is a version of a traditional tale. A version is simple a recognisable and fairly faithful duplication of a tale type. There are almost endless versions of popular folklore tales in your library and online, many of which are close duplications, or retellings, that mimic the motifs, patterns, values, imagery, and narrative structure of a shared variant.

Each variant of a tale type is sufficiently different to other variants to be unique. Different variants often reflect the influence of different contexts (culture, time) and stakeholders (tellers, transcribers, editors, publishers, etc) in their production.

Every single example of a fairy tale that you encounter is a version of a tale type; but these versions can be sorted into sets of a much more limited set of variants.

To use an example, there are endless versions of ATU333 little red riding hood, but these can be grouped into known variants. It’s easy to gather an almost endless array of different versions of ATU333, but much rarer to discover a new variant: a version that is sufficiently similar to the tale type to be recognisably part of the set, but also sufficiently different to all the known variants recorded to be a unique addition.

Now that we’ve considered these shared features of folklore narratives, I want to get closer to describing fairy tales from a folklore perspective, by considering four dominant forms or genres of folkloric narrative: fables, myths, legends, and fairy tales. Here, we’re looking less at what folklore narratives have in common, and more at their differences.

In her fabulous and truly accessible Folklore 101: An accessible introduction to folklore studies (2021), Jeana Jorgensen provides a four-part rubric: a tool for ‘breaking down folklore genres into their individual components: content, context, form, and function’ (p. 159). She writes:

Content is what the thing is or what’s in the thing, context is who/when/where the thing is transmitted, form is how the thing is transmitted and what shape it takes, and function is why the thing is transmitted or what its overall purpose is (p. 159).

In the below discussions, I’ve explored some of these elements, but focused in on two, in particular, as handy-dandy tools for distinguishing between the four types of folklore narratives I’ve looked at: Function (in other words, what purpose do these stories serve?) and Truth-i-ness, which is (I think) an aspect of the tale that’s partly Jorgensen’s form.

As Sara Cleto and Brittany Warman argue, the fastest way to determine whether a folklore narrative is a legend, fable, myth, or fairy tale, is to ‘Ask the question “what is the truth status of this story?”’ (2020, np).

The below description of four types of folklore narrative owes a great deal to Jeana’s excellent introduction to folklore, to Sara and Brittany’s post (Myth vs Legend vs Fairy Tale) on their Carterhaugh blog, and to the work of Ceallaigh MacCath-Moran, whose website, Folklore & Fiction, and related newsletter Folkbyte are a rich source of folklore research and discussion.

Fables

Most of the students I teach base their understanding of fables on Aesop’s fables, since these are the ones they were most often introduced to as young readers. Aesop’s fables share most of the features we associate with fables in their more international form. They are usually very short narratives that feature anthropomorphised animals as protagonists, are highly didactic in that everything in their compact stories points to the moral or ethical lesson they include, and conclude with a moral, or epimythium.

According to Zafiropoulos:

The Greek fable is a brief and simple fictitious story with a constant structure, generally with animal protagonists (but also humans, gods, and inanimate objects, eg: trees), which gives an exemplary and popular message on practical ethics and which comments, usually in a cautionary way, on the course of action to be followed or avoided in a particular situation …

The majority of Greek and modern definitions of fable can be summed up in the definition given by Theon, a Greek rhetorician of the second century AD … [who writes that] a fable is a fictitious narration that protrays reality. Most of the modern definitions … expand Theon’s. For example, a fable is “a fictitious statement wherein one or more animals or inanimate objects are introduced as speaking or acting, or both, in the manner of types, to illustrate either a parallel set of circumstances or a general principle” (2001, p. 1)

[The embedded quotation is from HT Archibald’s 1902 article ‘The fables in Archilocus, Herodotus, Livy, and Horace’]

The epimythium that concludes a fable is a unique characteristic of the form, though some fairy-tale writers also includes similar moral conclusions. Perrault, for example, often appends rhyming moral statements to the end of his tales.

As BE Perry notes, epimythia are particular in a variety of ways, he writes:

When the moral of a fable stands apart at the end, which is not always the case, we have what is properly called an ‘epimythium.’ Herein the author, speaking in his own person, explains to us—often against our will and Minerva’s—what the preceding story means in terms of general principles. He makes an application that is always general or gnomic, never specific; and he does so usually in the spirit of an interpreter. In the manuscripts the epimythium is often called the … ‘solution’, as if the foregoing fable were a riddle to be solved (1940, p. 391).

It’s a common misperception that, like fables, fairy tales are moral narratives, told explicitly to teach (usually conservative and Christian) morals. While this is certainly true of some fairy tales, it is not true of the genre as a whole. In fact, unlike fables, many fairy tales are enigmatic in terms of their moral meaning or messages.

Two key features of the fable:

True/not true? Fables are not intended to be read as literally true, but as analogical tales, like parables, that use fiction to teach lessons about morality and practical ethics.

Role in culture? Fables are best understood as morality tales, intended to teach the reader practical moral or ethical lessons. Sometimes these lessons, as in Aesop’s fables, are offered as an epimythium at the end of the tale; sometimes, as in the fables in the Panchantantra, fables ‘present strong arguments for both sides of an issue, citing proverbs containing age-old wisdom and narrating illustrative stories in support of both’ (Olivelle 2009, xxxiv).

Myths

In his influential 1965 essay, William Bascom provides a detailed and robust definition of a myth. He writes that:

Myths are prose narratives which, in the society in which they are told, are considered to be truthful accounts of what happened in the remote past. They are accepted on faith; they are taught to be believed; and they can be cited as authority in answer to ignorance, doubt, or disbelief. Myths are the embodiment of dogma; they are usually sacred; and they are often associated with theology and ritual. Their main characters are not usually human beings, but they often have human attributes; they are animals, deities, or culture heroes, whose actions are set in an earlier world, when the earth was different from what it is today, or in another world such as the sky or underworld. Myths account for the origin of the world, of mankind, of death, or for characteristics of birds, animals, geographical features, and the phenomena of nature. They may recount the activities of the deities, their love affairs, their family relationships, their friendships and enmities, their victories and defeats. They may purport to “explain” details of ceremonial paraphernalia or ritual, or why tabus must be observed, but such etiological elements are not confined to myths (Bascom 1965, p. 4).

Additionally, according to Cleto & Warman:

The colloquial usage of the term “myth” is, confusingly, almost the opposite of its folkloric use; labeling a story as a myth is a strategy frequently used to discount it, to insist that it is untrue. However, within the field of folklore, a myth is a narrative that is deeply true to the community from which it springs.

This is something the term ‘myth’ shares with the term ‘fairy tale’, which is also often used colloquially to dismiss an idea as fantastical or untrue. In everyday usage, the phrase ‘it’s just a fairy tale’ is often used to dismiss a story or idea as fanciful, overly romantic or idealistic, or false. This can sometimes be used in a positive sense, but more often it’s used to describe something that offered sparkling wonders, but didn’t or never could deliver.

Two key features of myths:

True/Not true? Myths were or are intended to be read as true within their cultural context. Importantly, the assertion that myths are or were understood as true doesn't have to mean that folk reading them now, or folk reading them from outside the culture within which they arise or are maintained, believe them to be historically or literally accurate or representative of our cultural or scientific truths.

Role in culture. Myths are sacred narratives. Especially when they are part of a living culture, they hold a special place in the spiritual lives of that culture and its people.

Legends

Legends are perhaps, along with fairy tales, the most difficult to define forms of folklore narrative. Since our focus here is on better understanding fairy tales, let’s start with a quote from Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm, which many scholars cite as the starting-point of attempts to define and delimit legends as compared to other forms of folklore narrative:

The fairy tale is more poetic, the legend is more historical; the former exists securely almost in and of itself in its innate blossoming and consummation. The legend, by contrast, is characterized by a lesser variety of colors, yet it represents something special in that it adheres always to that which we are conscious of and know well, such as a locale or a name that has been secured through history. Because of this local confinement, it follows that the legend cannot, like the fairy tale, find its home anywhere. Instead, the legend demands certain conditions without which it either cannot exist at all, or can only exist in less perfect form (Grimm & Grimm cited in Ben-Amos 2010, p. 433, emphasis added).

According to the Grimms, then, one of the key differences between a legend and a fairy tale is that a legend is located in a specific and real place and time. A second is that while fairy tales are fantastical, legends are realist. This accords with William Bascom’s definition, which is:

Legends are prose narratives which, like myths, are regarded as true by the nar- rator and his audience, but they are set in a period considered less remote, when the world was much as it is today. Legends are more often secular than sacred, and their principal characters are human. They tell of migrations, wars and victories, deeds of past heroes, chiefs, and kings, and succession in ruling dynasties. In this they are often the counterpart in verbal tradition of written history, but they also include local tales of buried treasure, ghosts, fairies, and saints (1965, pp. 4—5).

Another important feature of legends, including urban legends, is that they’re often conversational, sometimes even gossipy, in tone. This is something that’s expressed clearly in Brown and Rosenberg’s definition, from The Encyclopedia of Folklore and Literature:

Legend is a conversational narrative whose reported events are set in historical (as opposed to myth’s cosmological) time and whose telling makes possible debate concerning the “real world” occurrence and/or efficacy of the events, characters, folk beliefs, and/or folk customs described. Many legends are migratory—that is, their variants are widely known across different geographical areas. For this reason, as well as the fact that legends deal typically with the ambiguous and the unusual, their plots, character types, and motifs can provide a sense of both familiarity and strangeness for those literary works and films that draw upon them (Brown and Rosenberg 1999, p. 375, emphasis added).

Isn’t that wonderful! I love the notion that contemporary works that draw on traditional legends can ‘provide a sense of both familiarity and strangeness’. This is something that Marina Warner also refers to in her ten-point definition of the fairy tale, which I summarise and comment on towards the end of this essay.

Finally, legends come in a variety of forms, which have been the subject of much scholarly debate. According to Jeana Jorgensen, some of the categories of legends include:

supernatural legends (things like ghost stories and hauntings), and historical legends (ones that do not usually contain supernatural elements, but rather are based on real, documented events) … [as well as] urban legends, which are legends set in a modern time and place, usually not with supernatural elements. Folklorists tend to refer to them as contemporary legends (2021, np, emphases added).

In terms of those two key features:

True/Not true? Legends, including urban legends, have an ambiguous and contested relationship to historical and/or contemporary reality. They often include supernatural events or characters (ghosts! vampires! werewolves!), which adds to their contested nature. Legends are, to put it another way, not verifiably true.

Role in culture. Unlike myths, legends are not sacred narratives, tied to religious beliefs or spiritual practices, but they often convey the shared beliefs of a culture, embody shared values, and/or tell us something important about a culture’s customs and their associated beliefs.

Fairy tales

Definitions of folkloric fairy tales are rife, contradictory, and often highly contested. In what follows I begin with a general folklore definition, and then summarise three complementary descriptions or definitions to round out our understanding.

While ‘fairy tale’ is the most ubiquitous English-language term for these tales, other terms often used by scholars and other experts include ‘wonder tale’ (from the German Wundermärchen) and märchen (both terms/translations of terms that the Grimms used).

The term ‘fairy tale’ comes into English from a woman who is sometimes said to be the inventor of the literary fairy tale: Marie-Catherine Le Jumel de Barneville, Baroness d'Aulnoy (Mme d'Aulnoy, 1650-1705).

In 1690, d’Aulnoy published Histoire d'Hypolite, comte du Duglas, which contains the earliest known literary fairy tale: L'Île de la félicité (The Isle of Happiness). But she is most well-known for her two collections of fairy tales, Les contes des fées (Tales of the Fairies, first published 1697-1698) and Contes nouveaux ou les fées á la mode (New tales, or fairies in fashion, first published in 1698). To describe these works, and the readings and performances of them that she hosted in her salons, d’Aulnoy coined the term contes des fée, or fairy tale. Her practice of writing, publishing, and performing fairy tales established a literary fairy-tale fad that exploded in popularity and reach, first within the aristocratic salons of seventeenth-century Paris, and from there to the rest of Europe and the Western world.

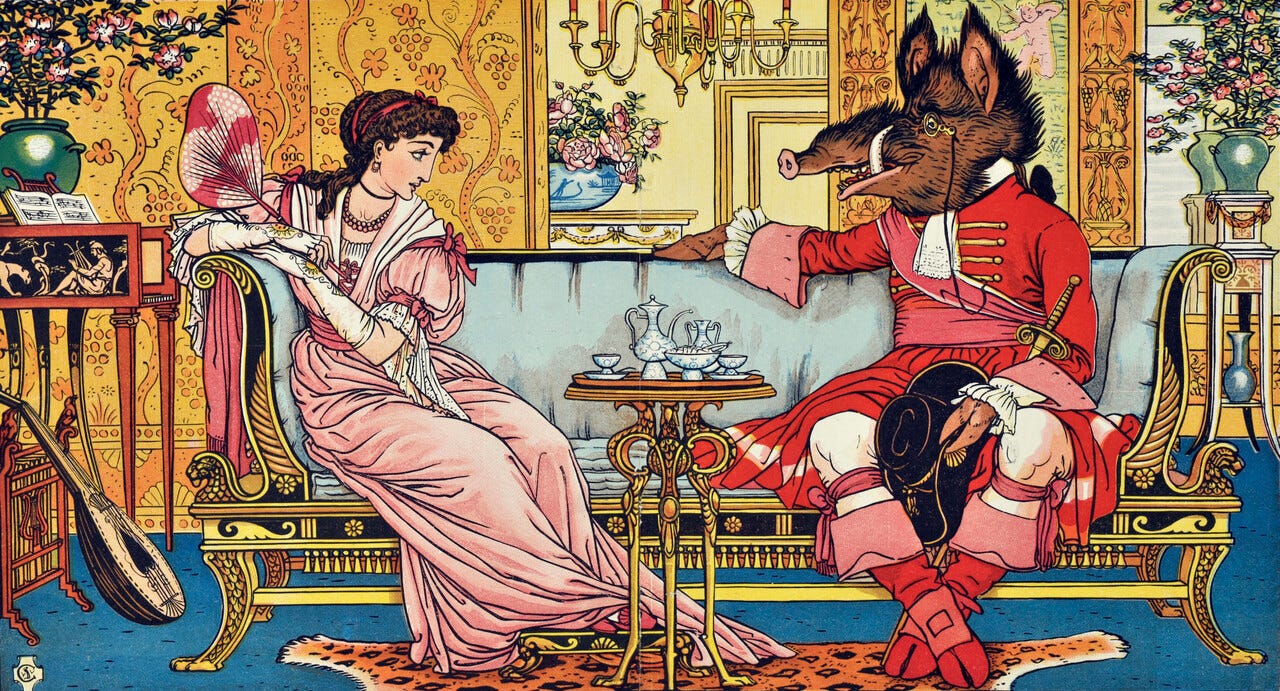

Aside: This is not to assert that d’Aulnoy invented the genre of fairy tales—as Lewis Seifert writes, ‘d'Aulnoy rewrote 15 different oral tale types ... She seems to have been particularly fascinated by the animal spouse cycles’ (Seifert in Zipes 2015, p. 33)—rather, she is often credited with inventing the literary, or written, genre of fairy tales that draws on and references folkloric materials).

The use of the term contes des fées to describe these early literary fairy tales is significant, and only partly relates to the common presence within the tales of powerful and precocious fairies. As Jack Zipes notes:

there is no other period in Western literary history when so many fairies, like powerful goddesses, were the determining figures in most of the plots of tales written by women—and also by some men. These tales were programs of actions or social symbolic acts projecting moral and ethical conflicts in alternative worlds ... we must recall that the French women writers were all members of literary salons, where they told or read their tales before having them published. These private salons afforded them the opportunity to perform and demonstrate their unique prowess at a time when they had few privileges in the public sphere. The fairies in their tales signal their actual differences with male writers and resistance to the conditions under which they lived ... It was only in the fairy-tale realm, not supervised by the church or subject to the dictates of King Louis XIV, that they could project alternatives stemming from their desires and needs (Zipes 2012, p. 24).

d'Aulnoy's contribution to the development of the literary genre of fairy tales is particularly significant for its focus on women, and on tales that expressed feminist values and concepts of her time. As Zipes writes, d'Aulnoy's tales:

… placed women in greater control of their destinies than in fairy tales by men. It is obvious that the narrative strategies of her tales, like those she told or learned in the salon, were meant to expose decadent practices and behaviour among the people of her class, particularly those who degraded independent women ... What interested her most of all was the status of women, the power of love, ethical behaviour, and the tender relations between lovers. Without love and the cultivation of love, she believed the ideal and just society could not exist (cited in Aulnoy 2021, p. xvi).

As the genre of the fairy tale has emerged and evolved over the centuries since d’Aulnoy's time, it has become more strongly associated with male writers and collectors—folk like Charles Perrault, the Grimm brothers, Hans Christian Andersen, and Walt Disney. Although a strong focus on tales about women and girls is still part of this long-lived tradition.

There are, of course, other terms for fairy tales. Hans Christian Andersen, for example, used the Danish term eventyr, and Asbjornsen and Moe referred to the tales they collected as folkeeventyr.

While there is a clear connection between the French contes des fées of the seventeenth century, and the German Wundermärchen of the nineteenth century, it’s perhaps worth noting that while we mostly we focus on the similarities, relationships, and continuity between these and other similar traditions, our focus on sameness and continuity sometimes blinds us to cultural and narrative differences.

A useful analogy might be to consider the word ‘bread’ and the various forms of the foodstuff made from flour (or meal) and water that it refers to.

We use, in English, the English word ‘bread’ to refer to French, Italian, and German bread (just as we use the word ‘fairy tale’ to refer to French, Italian, and German tales). In doing so, we emphasis the similarity between these different foodstuffs. Nevertheless, we know that there are also significant differences. Le pain is not the same thing as das Brot, or il pane. Consider, too, that the greater the difference between the cultures whose bread we are referring to—the more cultural and linguistic differences—the more difference there is in the bread itself. This is most marked and significant when we consider the challenge of using Western folklore theories, models, and terminology to describe and analyse non-Western storytelling. There is a tension here between the urgent need to be more inclusive of diverse narrative traditions in folklore, and the various dangers associated with looking at culturally and linguistically diverse narrative traditions through a Western and often colonialist gaze.

But what is a fairy tale, according to contemporary folkloric scholarship? I’d like to start by considering the two key features I’ve pulled out in relation to fables, myths, and legends, and build from there.

Two key features of fairy tales:

True/Not true? Traditional fairy tales are not true stories, and not intended to be read as such. They take place in a fictional, alternative version of the real world, often a world infused with the supernatural (with wonder), and are stories about fictional characters. If there is any ‘truthiness’ in fairy tales, it is often metaphorical or analogical, and related to their depiction of real-world social and cultural phenomena or structures, such as families, class systems, and gender/sexuality.

Role in culture. The role of fairy tales is historically more unstable than that of legends, fables, and myths. Traditional tales that were recorded prior to the flourishing of literary fairy tales in France in the seventeenth-century were often not as explicitly pedagogical as fables or legends, but they were consistently concerned with culture and politics: they were often stories about power and disempowerment, class, gender relations, human-nonhuman relations, marriage and gendered relations. As noted above, d’Aulnoy (and many other writers from the French salon tradition) used fairy tales to comment on and critique their social and political context. The Grimms intended, when they began collecting fairy tales (and other folklore narratives) to publish them as expressions of a specific culture and its heritage (peasant or working-class German culture): they wanted to use the tales as evidence of the beliefs, practices, and values of a folk culture that they believed was dying out. Over time, the changes the Grimms, and their translators, made to their tales reflected and contributed to a growing shift in the role of fairy tales, from stories primarily shared among adults that offered (sometimes veiled) social and political critique, to stories whose primary audience was children, with simplified, more explicit, and more mainstream (less ambiguous or subversive) moral messages.

In Bascom’s article—which I’ve drawn on here in talking about both myths and legends, he provides a comparative table for three forms of narrative. Here’s a reproduction of his section on myth and legend, to which I’ve added the two rows on fable and fairy-tale:

While the above discussion of these four forms offers, I hope, a strong sense of how fairy tales are defined in relation to folklore more broadly, and in relation to some other forms of folklore narrative, I want to also offer some complementary approaches to defining the fairy tale, starting with Ruth Bottigheimer’s provocative arguments concerning Straparola and the history of the fairy tale.

Rise and restoration tales

Something of an outlier in contemporary fairy tale scholarship, Ruth Bottigheimer’s complementary definition of a fairy tale focuses strongly on the narrative structure of fairy tales. Bottigheimer has, over the course of a long career as a folklore academic, consistently challenged mainstream folklore scholarship around core beliefs or theories, including the importance of the oral tradition to the definition of folklore, and to the transmission of fairy tales.

Her definition of fairy tales relies largely on a close reading of Straparola’s Facetious nights, and on her associated assertion that its Venetian writer, Giovanni Francesco Straparola (ca. 1485–1558), invented the literary fairy tale. From this premise—that Straparola’s tales are the origin of fairy tales and therefore the definitive form—Bottigheimer makes some familiar, and some surprising and provocative, conclusions, including:

that fairy tales take part in the ordinary human world, with the occasional intrusion of magic or magical beings;

that fairy tales are short stories;

that there are two types of fairy tales: ‘rise’ tales, and ‘restoration’ tales;

Restoration tales are somewhat longer than rise tales, and: ‘they begin with a royal personage—usually a prince or princess, but sometimes a king or queen—who is driven away from home and heritage. Out in the world, the royals face adventures, undertake tasks, and suffer hardships and trials. With magic assistance they succeed in carry- ing out their assigned tasks, overcoming their imposed hardships, and enduring their character-testing trials, after which they marry royally and are restored to a throne, that is, they return to their just social, economic, and political position’ (Bottigheimer 2009, p. 10).

Rise tales are shorter. According to Bottigheimer, they ‘begin with a dirt-poor girl or boy who suffers the effects of grinding poverty and whose story continues with tests, tasks, and trials until magic brings about a marriage to royalty and a happy accession to great wealth’ (2009, p. 11-12)/

that ‘rise’ tales are more modern, and were invented by Straparola, and finally;

that ‘rise’ tales, in particular, are urban stories. That is, that they are ‘firmly embedded in the imagery, characters, and references of city life’ (Bottigheimer 2009, p. 18).

Reducing our notion of what fairy tales are to these two literary (not oral) narrative forms—rise tales, and restoration tales—is certainly an effective way to reduce the genre to a more compact and easily-defined genre. While not as generous, expansive, or inclusive as the more common scholarly definitions, it certainly provides us with a neat way to describe some fairy tales, and to distinguish between two dominant narratives in fairy tales that focus on characters and class.

The next approach to describing the fairy tale I want to share with you comes from a quite different perspective: that of a writer of fairy tales, a scholar of the form, and the editor of the marvellous contemporary magazine, Fairy Tale Review: Kate Bernheimer.

Fairy tale as form, form as fairy tale

In her essay ‘Fairy tale is form, form is fairy tale’ Kate Bernheimer offers a complementary approach to describing traditional fairy tales. While her essay doesn’t exactly offer a definition of traditional fairy tales, it does name and describe four key features of traditional fairy-tale form: flatness, abstraction, intuitive logic, and normalised magic.

Flatness

In traditional fairy tales, according to Bernheimer, characters are always flat. That is, they lack the psychological depth that we associate with real people, and with depictions of characters in most contemporary fiction.

Abstraction

Just as characters are shown as lacking particularity and psychological complexity, other phenomena and objects in traditional fairy tales are, according to Bernheimer, represented in abstract form, rather than through concrete and specific imagery. The combination of flatness and abstraction lends traditional tales a sense of simplicity. A sense that everything is reduced to its most essential form. A wolf, a forest, a girl in a red hood.

Intuitive logic

According to Bernheimer, traditional fairy tales use ‘intuitive logic’. She says:

Despite their reputation as plot-driven narratives, fairy tales are actually extremely associative when you begin to unstitch them … this associative quality is also a sort of violation, a violation of the rule that things must make sense. Many fairy tales rely on the sensed relationship of words to story— the art of putting words together in a strange yet marvelous order that simply feels right, no matter how difficult it is to take it apart and try to put it back together again with everyday logic. A fairy tale is a Humpty Dumpty (p. 69).

Normalised magic

Finally, Bernheimer describes traditional fairy tales as consistent in employing ‘normalised magic’. As she writes:

The natural world in a fairy tale is a magical world. The day to day is collapsed with the wondrous. In a traditional fairy tale there is no need for a portal. Enchantment is not astounding. Magic is normal (p. 69).

At the end of her essay, Bernheimer offers an evocative and provocative statement about the effect that these four features of fairy tales produce:

With their flatness, abstraction, intuitive logic, and normalized magic, fairy tales hold a key to the door fiercely locked between so- called realism and nonrealism, convention and experimentalism, psychology and abstraction (p. 70).

Tales of wonder and hope

In Fairy tale: a very short introduction (2018), Marina Warner provides a ten-point definition of the classic fairy tale. I want to conclude with this definition—or at least a summary of it—because I feel it draws together and consolidates a lot of the other definitional approaches I’ve explored above. And so, perhaps, provides a robust, flexible, and workable definition that, while not monolithic—not impervious to critique or revision—is useful, plain, and clear.

According to Warner, a fairy tale:

is a short narrative;

is a familiar story;

I find this one of the least convincing of Warner’s defining characteristics, since while many fairy tales are familiar to many of us, there are also many fairy tales that are obscure, or forgotten.

is a form of folklore narrative;

may be oral or literary;

reflects or expresses the wisdom of, and/or expectations of a culture or social group;

reflects the past while interweaving the present through transformations of familiar plots, characters, devices, and images;

is generically recognisable as a fairy tale, even when the specific story type is not clear;

is expressed in a recognisable style, or voice. (According to Warner, ‘fairy tale consists above all of acts of imagination, conveyed in a symbolic Esperanto’ [2018, p. xxv, emphasis added]). She describes the voice or style of the fairy tale as ‘one-dimensional, depthless, abstract, and sparse’ (2018, p. xxvi);

This, too, I would push back against. While the notion that fairy tales are always written in a simple and compact voice is a commonly-held one, this is largely a result of the bowdlerisation of fairy tales that began with the Grimms. As Wendy Wanning Harries notes, historically there are at least two approaches to voice or style in the fairy tale: the compact and simple style we associate with the Grimms, and with fairy tales ‘retold’ for children, and the more expansive, digressive, and complex style of Straparola, Basila, and the seventeenth-century French conteuses.

must elicit a sense of wonder from the audience/reader, and finally;

offers hope, usually through the generic ‘happy ending.’

A happy ending?

Defining traditional fairy tales is a fraught but productive challenge. It offers us an opportunity to identify how this particular form of storytelling has evolved over time, and to reflect on the features of the fairy tale that we most treasure. It provides us with some insights into the history of storytelling, writing, editing, and publication, particularly within Western Europe. And reminds us that storytelling and folklore are inherently political: how we choose to define fairy tales—what tales and tellers we exclude, what we include, what parameters we consider important and which irrelevant—tells us as much about who we are now, as they do the fairy tale practitioners and traditions of the past.

Mostly, I think, what this exploration reveals is that the genre of fairy tales is and has always been dynamic, evolving, and significant. It is no surprise to discover that fairy tales are still in the process of evolving, and that defining what traditional fairy tales are is a high-stakes game, with various stakeholders determined to redefine fairy tales to fit their own (our own!) agendas and tastes.

However we define traditional fairy tales, what also remains clear is that they are dynamic and powerful forms of storytelling, that the genre of fairy tales is still evolving, and that our understanding of the genre—its history and its form—is also still evolving as we discover more historical evidence and examples, and challenge the limiting or false assumptions that have underscored previous approaches to describing and studying them.

Finally, while considering various definitions of traditional fairy tales, I have, in this essay, not even dipped a toe into defining contemporary fairy tales. However challenging it is to define and describe traditional fairy tales, I promise you it is even more challenging to try to describe the diverse range of works that are part of the contemporary fairy-tale web! A challenge we may take up in a future issue of The Orange & Bee!

References

Aulnoy, Madame d' 2021, The island of happiness: tales of Madame d'Aulnoy, trans. Jack Zipes, Princeton, Princeton University Press.

Bascom, W 1965, ‘The forms of folklore: prose narratives’. The journal of American folklore, vol. 78, no. 307, pp. 3–20.

Ben-Amos, D 2010, ‘“It happened not too far from here …”: a survey of legend theory and characterization’, Western Folklore, Vol. 49, No. 4, pp. 371-390.

Ben-Amos, D 2014, 'A definition of folklore: a personal narrative', Studies in oral folk literature, vol. 3, pp. 9-28.

Bernheimer, K 2009, ‘Fairy Tale is Form, Form is Fairy Tale’, in The Writer’s Notebook, Tin House Books, Portland, pp. 61-73.

Bottigheimer, R 2009, Fairy tales: a new history, Albany, State University of New York Press.

Cleto, S & B Warman 2020, ‘Myth vs legend vs fairy tale’, The Carterhaugh school, online article, viewed 20 March 2023, <https://carterhaughschool.com/myth-vs-legend-vs-fairy-tale/>,

Dégh, L 2001, Legend and belief: dialectics of a folklore genre, Bloomington, Indiana University Press.

Harries, EW 2001, Twice upon a time: women writers and the history of the fairy tale, Princeton & Oxford, Princeton University Press.

Jorgensen, J 2021, Folklore 101: An accessible introduction to folklore studies, Kindle version, LLC.

MacCath-Moran, C nd, Folklore & Fiction, viewed 9 September 2024, <https://csmaccath.com/folkloreandfiction>.

Olivelle, P (trans.) 2009, Pañcatantra: the book of India’s folk wisdom, first edition, Oxford and New York, Oxford University Press.

Perry, BE 1940, ‘The origin of the epimythium’, Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association, Vol. 71, pp. 391-419.

Sims, M & M Stephens 2005,Living folklore: introduction to the study of people and their traditions, 2nd edition, Logan, Utah State University Press.

Tatar, M 2019, The hard facts of the Grimms' fairy tales, expanded edition, Princeton & Oxford, Princeton University Press.

Warner, M 2018, Fairy tale: a very short introduction, Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Zafiropoulos, CA 2001, Ethics in Aesop’s fables: the Augustana collection, Leiden, Brill.

Zipes, J 2002, Breaking the magic spell: radical theories of folk and fairy tales, Lexington, University Press of Kentucky.

Zipes, J 2012,The irresistible fairy tale: the cultural and social history of a genre, Princeton & Oxford, Princeton University Press.

Zipes, J (ed.) 2015,The Oxford companion to fairy tales, Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Thanks for this essay, Nike - simultaneously detailed and completely accessible for someone like me! I've not come across that delineation between myth and legend before, and it's left me with a lot to think about.

The to and fro of oral and written tales is a fascinating one that will surely continue to excite and bamboozle academics forever.